The distinction between a protocol deviation and a protocol amendment is defined by timing and intent. A protocol deviation is an unplanned departure from the approved study protocol, documented retrospectively. In contrast, a protocol amendment is a prospective, deliberate change to the protocol, formally documented and approved before implementation. While the concepts are distinct, their documentation implications are deeply interconnected, particularly within the Trial Master File (TMF) and for regulatory reporting.

This guide explores the documentation lifecycle of each event, their relationship to the TMF, and their impact on the final Clinical Study Report (CSR), focusing on the operational and regulatory rationale for these distinct processes.

Understanding the Core Definitions

Adherence to the clinical trial protocol is fundamental to ensuring participant safety and generating reliable data. However, divergences from the protocol are inevitable. How these events are managed and documented is a critical component of Good Clinical Practice (GCP).

A protocol deviation is any accidental or unintentional departure from the procedures and requirements defined in the IRB/EC-approved protocol. These events are documented reactively. The documentation creates an audit trail explaining why the trial’s conduct did not align with the protocol for a specific participant at a specific point in time.

A protocol amendment is a formal, written revision to the protocol. It is a proactive and controlled process to modify, clarify, or correct the trial design or procedures for all participants moving forward. The documentation for an amendment centers on planned change management, including regulatory and ethical review and approval prior to implementation. The fundamentals of protocol development for clinical trials provide context for how these foundational documents are structured and revised.

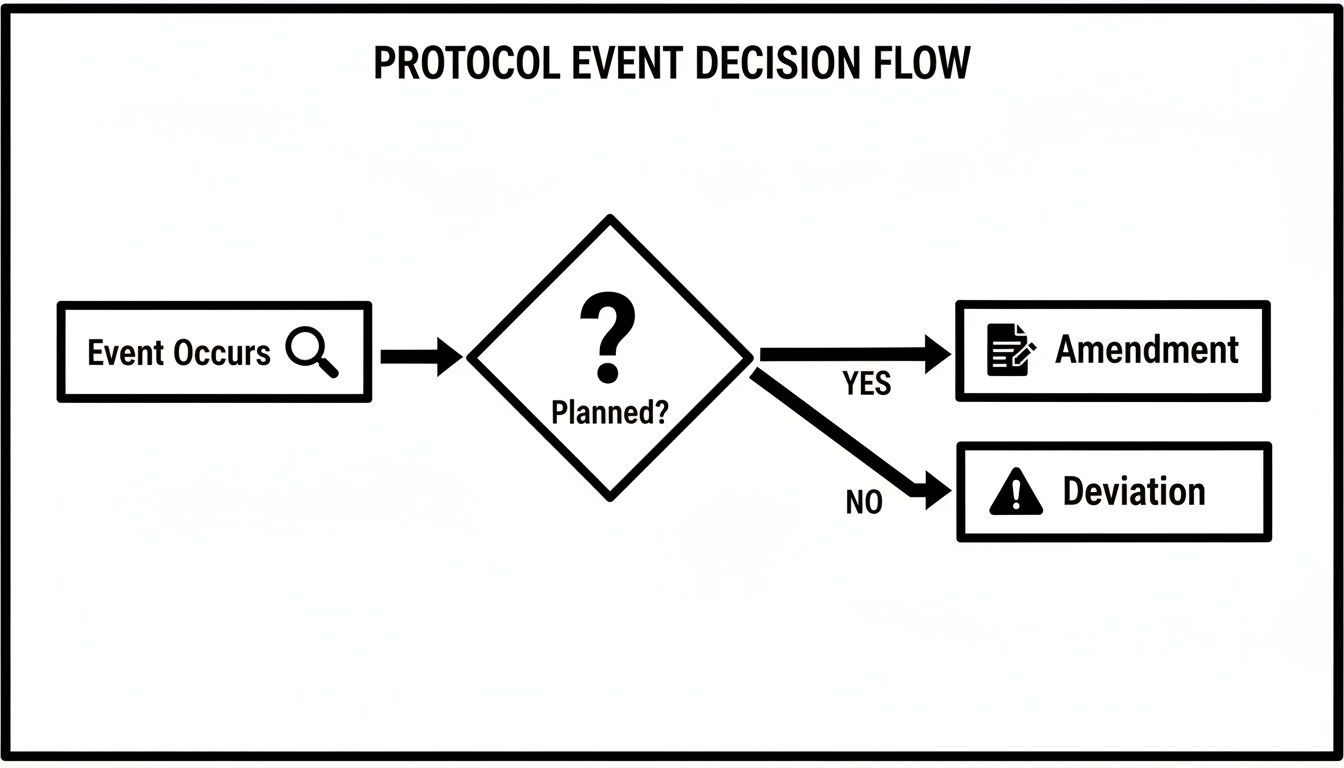

This decision tree illustrates the core distinction: was the divergence from the protocol planned and pre-approved? This question differentiates a deviation from an amendment.

As the flowchart indicates, an unplanned event is a deviation that requires reactive documentation. An intended change requires a prospective, formal amendment process.

Core Documentation Differences: Protocol Deviations vs. Amendments

The documentation requirements for deviations and amendments are distinct and serve different regulatory purposes. They are not interchangeable. Deviations generate records of non-conformance and its management, while amendments create new, authoritative versions of core trial documents.

This table outlines the key documentation distinctions.

| Attribute | Protocol Deviation | Protocol Amendment |

|---|---|---|

| Timing | Retrospective (after the event) | Prospective (before the change is implemented) |

| Nature | Unplanned departure from the protocol | Planned, formal revision to the protocol |

| Documentation | Deviation report/log, sponsor impact assessment, CAPA records, notes-to-file | Amended protocol document (clean and redlined), submission records, IRB/EC approval letters, updated ICFs |

| Approval | None (it is an instance of non-compliance) | Required from IRB/EC and regulatory authorities before implementation |

| TMF Impact | Adds records of non-conformance, assessment, and resolution | Creates new versions of core trial documents (e.g., protocol, ICF, IB) |

Ultimately, deviation documentation explains a failure to adhere to the approved protocol, while amendment documentation establishes a new, approved standard for trial conduct moving forward.

The Documentation Lifecycle of a Protocol Deviation

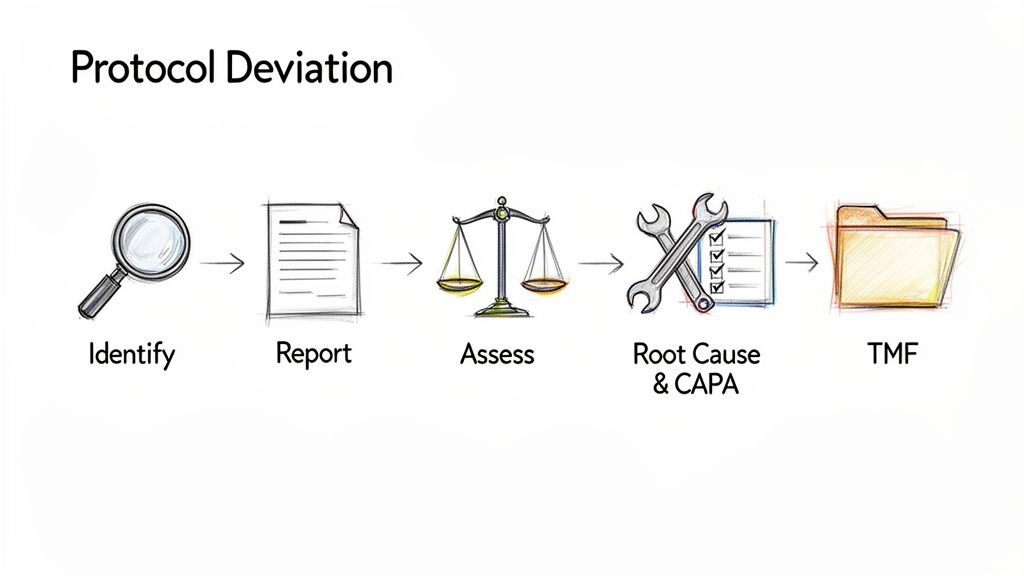

The occurrence of a protocol deviation initiates a reactive documentation workflow designed to record, assess, and manage the event. The objective is not to change the study protocol but to create a comprehensive and auditable record explaining a specific instance where the protocol was not followed. This process demonstrates sponsor oversight and transparency.

The documentation lifecycle begins at the point of identification, which may be by site staff, a monitor, or through data management review. Per ICH GCP E6(R2), the event must be recorded promptly and accurately.

From Site-Level Reporting to Sponsor Assessment

The initial record is typically made in a Protocol Deviation Log or a specific deviation reporting form at the clinical site.

This source record should include, at a minimum:

- A unique identifier for the deviation.

- The subject identifier.

- The date of the deviation and the date of discovery.

- A factual description of the event, with reference to the specific protocol section that was not followed.

Following initial logging, the site reports the deviation to the sponsor or designated CRO, typically the Clinical Research Associate (CRA). This communication, whether via email, a monitoring report, or a system entry, becomes part of the documented audit trail. The sponsor then conducts an assessment to classify the deviation based on its potential impact on subject safety, rights, and data integrity. This assessment and its rationale must be documented.

Creating an Auditable Trail in the TMF

All documentation related to a deviation must be filed in the Trial Master File (TMF) to provide a complete history of the event for auditors and inspectors. The goal is to demonstrate that the deviation was identified, evaluated, and managed appropriately.

Key documents filed in the eTMF for a deviation include:

- The initial deviation form or log entry: The source document from the site.

- Site and Sponsor Communications: Emails, meeting minutes, and monitoring follow-up letters related to the event.

- Impact Assessment Documentation: The sponsor's internal records showing the classification (e.g., major/minor) and the rationale.

- Root Cause Analysis (RCA) Reports: For significant or recurring deviations, a formal RCA is often conducted to determine the underlying cause.

- Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) Plans: If a CAPA is initiated, the plan, associated actions, and evidence of completion must be filed.

A protocol deviation is not an error to be hidden; it is an event to be managed. The quality of its documentation is a direct reflection of the sponsor’s commitment to trial oversight and data integrity.

Consider a common scenario: a participant misses a scheduled 30-day visit and returns on day 35. The documentation lifecycle would include the site's deviation log entry, communications between the site and CRA, and the sponsor's documented assessment concluding minimal impact on primary safety endpoints. This collection of records provides a defensible history, which is a core tenet of effective clinical trial document lifecycle management.

Navigating the Structured Workflow of Protocol Amendments

A protocol amendment is a deliberate, prospective modification to the trial. The process is a structured, multi-stage workflow designed to ensure controlled change management. It is initiated not to address a single past event, but to alter the study's design or procedures based on new information or strategic requirements.

The amendment workflow creates a new, official version of the protocol that governs trial conduct from the point of implementation, ensuring all sites and stakeholders operate under the same revised plan.

Triggers and Drafting the Revised Protocol

A protocol amendment typically originates from a substantive issue affecting the study’s scientific integrity, participant safety, or operational feasibility.

Common triggers for an amendment include:

- Emerging Safety Data: New information necessitates changes to safety monitoring, dosage, or eligibility criteria.

- Operational Feasibility: A consistent pattern of deviations may indicate that a protocol procedure is impractical, requiring revision to ensure compliance and data quality.

- Adjustments to Eligibility Criteria: Slow enrollment may prompt a sponsor to broaden inclusion or narrow exclusion criteria to meet recruitment targets.

- Changes in Standard of Care: The comparator therapy or supportive care defined in the protocol may become outdated, requiring an update to maintain clinical relevance and ethical standards.

Once the need for an amendment is confirmed, the drafting process begins. Meticulous version control is essential. The new document must have a new version number and date. All changes from the previous version must be clearly identified, often through tracked changes in a redlined version and a summary of changes table.

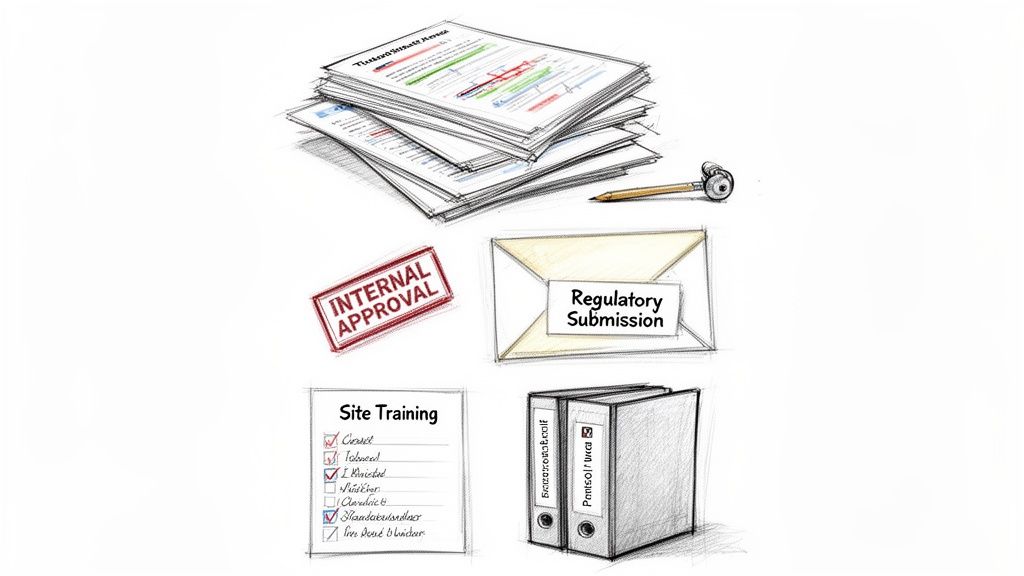

The Formal Approval and Implementation Cascade

Following internal finalization of the draft, a formal amendment package is prepared for submission to regulatory authorities and Institutional Review Boards/Ethics Committees (IRBs/ECs). The revised procedures cannot be implemented until all necessary approvals are obtained and documented.

The submission package is a collection of documents that must be tracked and filed in the TMF.

Key documents in the amendment package include:

- The Amended Protocol: Both a clean final version and a redlined version highlighting changes.

- Updated Investigator's Brochure (IB): Required if the amendment is triggered by new safety or efficacy data.

- Revised Informed Consent Form (ICF): Required if the changes affect a participant's risks, benefits, or trial procedures. The revised ICF must be approved by the IRB/EC.

- Regulatory Submission Forms: Cover letters and forms required by the FDA, EMA, or other competent authorities.

- IRB/EC Submission Package: The complete set of documents submitted to each ethics committee.

Upon receipt of approvals, the documentation process continues. Each approval letter is a critical artifact for the TMF. The sponsor then manages implementation, which generates its own documentation, including notifications to sites of the approved amendment and records of site staff training on the new protocol version.

A protocol amendment fundamentally redefines the "rules" of the study from a specific date forward. Its documentation trail must be flawless to prove that all sites were trained on and began following the new, approved procedures at the correct time.

This prospective, controlled process differs fundamentally from the retrospective management of deviations. An amendment’s documentation trail is one of authorization and planned evolution, while a deviation’s documentation trail is one of explanation and impact assessment.

How Deviations and Amendments Shape the Clinical Study Report

The Clinical Study Report (CSR) is the definitive narrative of a clinical trial, forming the basis of a regulatory submission. The quality and clarity of the documentation for both deviations and amendments are critical for constructing a transparent and defensible CSR.

Protocol amendments are reported in a straightforward manner. In accordance with ICH E3 guidance on the structure and content of CSRs, all protocol amendments are listed and described chronologically. This provides reviewers with a clear history of how and when the study design was formally changed.

Reporting Deviations in the CSR

Protocol deviations require a more analytical approach in the CSR. They are not merely listed; they must be summarized and analyzed for their potential impact on study outcomes. The CSR must contain a dedicated section detailing all important protocol deviations, drawing directly from the documentation maintained in the TMF throughout the study.

This section of the CSR should include:

- A summary of the types and frequencies of deviations that occurred.

- An analysis of any trends or patterns observed, such as recurring issues at specific sites or across the study.

- A discussion of how these deviations may have affected the integrity of the data and the study's primary and secondary endpoints.

- A rationale for the inclusion or exclusion of subjects' data from the final analysis based on their deviations.

This highlights a crucial difference in the reporting of protocol deviations vs. protocol amendments. Amendments define the intended study design at various points in time, while the deviation analysis describes the unintended departures from that design.

The Challenge of Volume and Complexity

The volume of deviations in a complex trial can present a significant challenge during CSR authoring. Medical writers and biostatisticians must analyze this information to construct a coherent narrative for regulators. A poorly justified or incomplete discussion of deviations in the CSR can be a major red flag for inspectors, suggesting a lack of trial oversight and potentially undermining confidence in the study's conclusions.

The Clinical Study Report translates raw TMF data into a scientific narrative. Flawless TMF documentation for deviations and amendments is the prerequisite for a CSR that is transparent, defensible, and capable of withstanding intense regulatory scrutiny.

For example, a high number of dosing deviations that are not adequately explained could lead regulators to question the validity of efficacy and safety data. A robust clinical study report template will allocate significant space for this critical analysis.

Ultimately, the CSR is where the separate documentation streams for deviations and amendments converge. Amendments provide the context by defining the approved protocol over time. The deviation analysis provides transparency regarding the actual adherence to that protocol.

Ensuring Audit Readiness

An effective documentation framework is essential for a successful regulatory inspection. This requires a proactive, system-driven approach to quality management, not last-minute remediation. A robust Quality Management System (QMS) should treat deviation management and amendment control as integrated components of trial oversight.

This begins with clear Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) that define the end-to-end process for identifying, reporting, and assessing deviations. These SOPs should be supported by standardized templates for deviation reporting to ensure consistent data capture across all clinical sites.

Building Quality Systems for Proactive Oversight

A common pitfall is treating deviation management solely as a retrospective activity. An audit-ready organization uses deviation data proactively. By analyzing trends, sponsors can identify systemic problems, such as a protocol procedure that is frequently misunderstood by site staff. This analysis may trigger a formal protocol amendment to clarify the procedure.

This creates a quality feedback loop: reactive data from deviations informs proactive protocol improvements. This demonstrates a mature approach to quality management. Key elements of this approach include:

- Standardized Templates: Consistent use of deviation logs and reporting forms enables meaningful trend analysis.

- Clear Definitions: The protocol itself should define what constitutes an "important" deviation to guide site-level reporting and sponsor assessment.

- Integrated QMS: Systems should facilitate the connection between a deviation, its subsequent CAPA, and the potential initiation of a protocol amendment.

The objective is not to achieve zero deviations, which is unrealistic in complex trials. The objective is to demonstrate robust control and transparency when they occur. The audit trail must tell a logical story: how the deviation was identified, how it was assessed, and how the issue was addressed.

The Role of the eTMF in Demonstrating Control

The electronic Trial Master File (eTMF) serves as the central repository of evidence for compliance. An effective eTMF is an operational tool that helps enforce documentation workflows and provides the traceability inspectors expect.

For deviations and amendments, the eTMF must demonstrate clear relationships between documents. For example, it must be possible to link a specific deviation report to the version of the protocol that was effective at the time of the event. It must also link a protocol amendment to all its related artifacts: IRB/EC approvals, the revised ICF, and site training records.

This network of linked documentation creates a complete and defensible audit trail. When an inspector asks for the history of a protocol change or the management of a significant deviation, the eTMF should allow for the rapid retrieval of a complete, chronological record.

Common Questions on Protocol Documentation

Operational teams frequently encounter complex scenarios involving protocol deviations and amendments. The following are common questions related to their proper documentation in a regulated environment.

When Does a Pattern of Deviations Require a Protocol Amendment?

A recurring pattern of the same deviation across multiple subjects or sites indicates a potential systemic issue. This should trigger consideration of a protocol amendment. If sites consistently struggle with a particular procedure, the protocol itself may be unclear, impractical, or difficult to execute. From a regulatory perspective, proactively amending the protocol to address a root cause is preferable to allowing numerous deviations to accumulate.

This approach shifts the process from reactive problem documentation to proactive quality management. The decision to amend should be based on a risk assessment of the recurring deviations' impact on participant safety, data integrity, and overall trial objectives.

A consistent pattern of deviations is not just a list of errors; it is data indicating a potential flaw in the protocol. An amendment is the data-driven solution, and the documentation should reflect this rationale.

What Documentation Is Needed for an Urgent Safety Amendment?

In cases where an immediate change is necessary to eliminate or mitigate a significant risk to trial participants, an amendment may be implemented prior to full IRB/EC approval. However, the documentation requirements are stringent.

The TMF must contain a complete record justifying the urgent action, including:

- A clear rationale explaining the nature of the immediate hazard.

- Copies of all communications directing sites to implement the change immediately.

- The formal amendment package subsequently submitted to regulatory authorities and IRBs/ECs.

- The subsequent approval letters from all reviewing bodies.

While the timing of implementation and approval is different, the documentation burden is heightened. A clear, contemporaneous audit trail is critical to defend the urgent action during an inspection.

How Should a Deviation Against a Previous Protocol Version Be Documented?

A protocol deviation must always be documented and assessed against the version of the protocol that was in effect at the time the event occurred.

When a new amendment is implemented, it does not retroactively apply to past events. The TMF must maintain all previous versions of the protocol and be structured to link each deviation record to the specific protocol version and its effective dates. This traceability is essential for proper contextualization of deviations and is a common focus area for regulators during an audit.