In clinical research, version control is a foundational component of data integrity, patient safety, and regulatory compliance. Effective version control establishes a single source of truth for every critical document, from the clinical trial protocol to the Informed Consent Form. Every change must be tracked, justified, and auditable to meet regulatory expectations and ensure the trial's scientific validity.

The Critical Role of Version Control in Clinical Research

Clinical trial documents are dynamic and evolve throughout a study's lifecycle. Protocols are amended, Investigator’s Brochures are updated with new safety information, and Statistical Analysis Plans are revised based on interim findings. Without a systematic approach to managing these updates, a trial can face significant compliance and data quality risks.

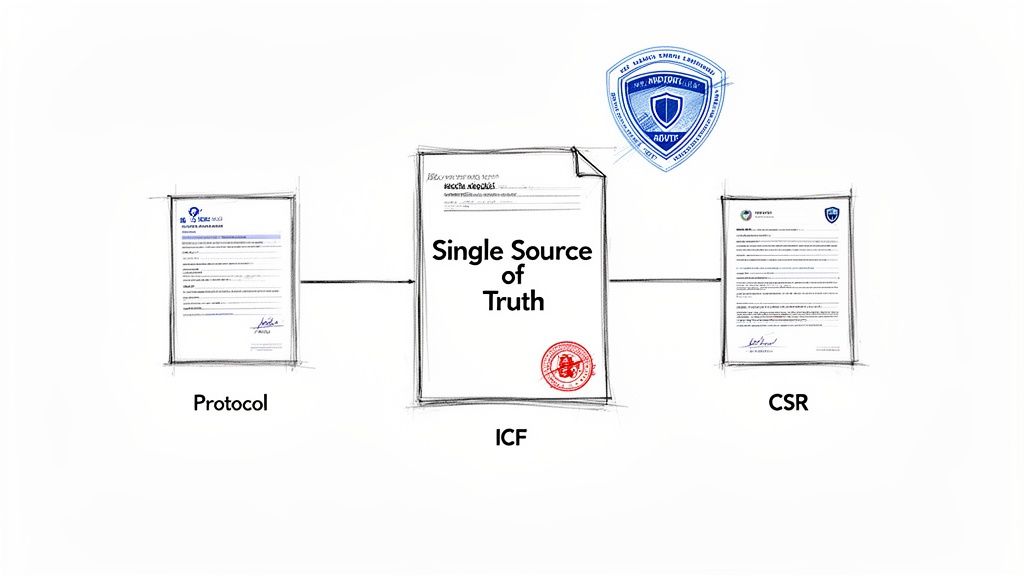

Proper versioning establishes a complete, auditable history for every document. This creates the single source of truth that all stakeholders—from clinical sites to CROs and sponsor teams—rely on. This principle prevents operational errors, such as different teams working from conflicting protocol versions, which could lead to deviations or compromise patient safety.

Connecting Version Control to Regulatory Intent

Regulatory authorities emphasize traceability and accountability in clinical trial conduct. While specific regulations may not mandate a particular version control system, the intent is clear: every action affecting the trial's conduct and data must be documented, with a clear record of who performed the action, when, and why.

This principle is embedded in key regulatory frameworks:

- ICH E6(R3): The updated Good Clinical Practice guideline emphasizes a quality-by-design, risk-based approach. This philosophy requires clear, controlled, and current documentation to be effective.

- FDA 21 CFR Part 11: This regulation sets the standard for electronic records and signatures. It requires secure, computer-generated, time-stamped audit trails that independently record the date and time of operator entries and actions that create, modify, or delete electronic records.

Version control for a Clinical Study Report (CSR) can be compared to a pharmaceutical batch record. Just as every ingredient, measurement, and manufacturing step must be meticulously logged to validate the final product, every change, review, and approval for a CSR must be tracked to ensure the final report is a valid and reproducible account of the trial.

Impact on Key Trial Documents

While robust version control is essential across the entire Trial Master File (TMF), it is particularly critical for documents that directly guide study conduct and protect participants. For example, an update to an Informed Consent Form (ICF) must be carefully versioned and distributed to all sites simultaneously to ensure new participants are consented using the correct, IRB/IEC-approved document.

Similarly, a protocol amendment that modifies inclusion criteria requires precise change management. If this process is not controlled, sites may risk enrolling ineligible subjects, which can undermine the integrity of the study's data. A robust version control system ensures the entire lifecycle of a document—from initial draft to final, approved version—is transparent and defensible during a regulatory inspection.

Laying the Groundwork for Compliant Document Versioning

Establishing a reliable version control system begins with a clear, enforceable procedural framework. This foundation is built on well-defined Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) that map the entire document lifecycle. Without this structure, even sophisticated software tools cannot prevent compliance risks.

The initial step is to eliminate ambiguity regarding a document's status. Confusion between a draft and an approved version can lead to significant errors, such as a clinical site using a protocol that is still under review. By establishing clear, universally understood document states, organizations can create a predictable and auditable process for all team members.

Defining Key Document States

Every document in a clinical trial progresses through a series of distinct phases. Standardizing these states ensures that all personnel, from medical writers to clinical research associates, understand a document's current status and whether it is suitable for operational use.

Common document states include:

- Draft: The document is under active development or revision and is not intended for formal review.

- In Review: The document has been circulated to relevant stakeholders for comments and feedback.

- Approved: The review cycle is complete, all required approvals have been obtained, and the document is considered the official, effective version.

- Superseded: A previously approved version that has been replaced by a newer one. This version must be archived and clearly marked as obsolete to prevent inadvertent use.

Mapping this lifecycle is a cornerstone of good documentation practice and is central to version control best practices for clinical trial documents. It provides an immediate indicator of whether a document is fit for its intended purpose.

Developing a Logical Naming Convention

With document states defined, the next pillar of a compliant framework is a logical and consistently applied naming convention. This is a critical tool for preventing errors, as a well-structured file name should convey a document's purpose, study affiliation, and version at a glance.

An effective naming convention functions like a document’s unique identifier. It provides immediate traceability, confirming its identity, version, and status. This is essential for both daily operations and regulatory inspections.

A robust naming convention should be detailed in an SOP and applied to all controlled trial documents. The structure should be human-readable and optimized for electronic sorting.

The table below outlines the key components of a standardized naming convention, using a protocol amendment as an example.

Standardized Document Naming Convention Components

| Component | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Document Type | A standard abbreviation for the document (e.g., PRO for Protocol). | PRO |

| Study Identifier | The unique protocol number assigned to the trial. | XYZ-123 |

| Version Number | A numeric indicator, often using a major.minor format (e.g., 2.0 for a major revision, 2.1 for a minor update). | v2.0 |

| Status | A short code indicating the document's current state (e.g., DRAFT, FINAL). | FINAL |

| Effective Date | The date the document becomes effective, formatted as YYYYMMDD for consistent sorting. | 20241028 |

Combined, these components create a file name that provides comprehensive information: PRO_XYZ-123_v2.0_FINAL_20241028.

This structure immediately identifies the document as the final, effective version 2.0 of the protocol for study XYZ-123. This systematic approach, supported by metadata such as the author and a summary of changes, creates the complete, auditable document history required for inspection readiness.

Managing Change Control and Maintaining Audit Trails

While versioning identifies a document's state, change control documents the history of how it reached that state. The two are interdependent. Change control is the process of systematically tracking, justifying, and approving every modification, providing the rationale for each new version and ensuring full accountability.

At its core, change control explains the "why" behind version 2.0 or 3.1. This is a fundamental requirement for regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA, which expect a clear, logical, and defensible narrative of a document's evolution.

Differentiating Major and Minor Versions

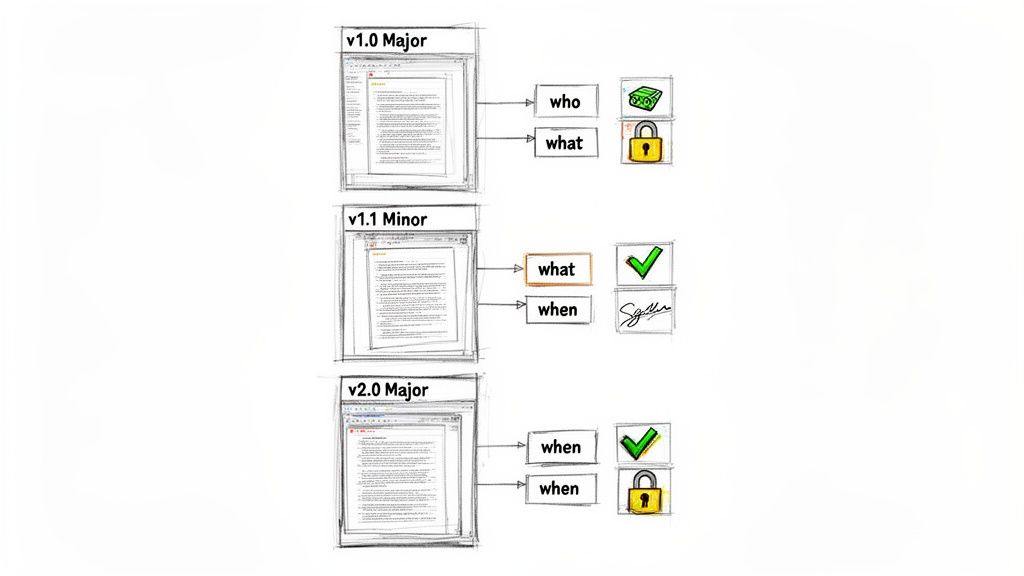

A key aspect of effective change control is distinguishing between major and minor updates. This distinction prevents formal review cycles for minor corrections while ensuring substantive changes receive appropriate scrutiny. Defining these rules in SOPs is one of the most critical version control best practices for clinical trial documents.

- Minor Versions (e.g., v1.1, v1.2): Reserved for administrative or editorial corrections that do not alter the scientific or operational meaning of the document. Examples include correcting typographical errors, fixing formatting, or adding a clarification.

- Major Versions (e.g., v2.0, v3.0): Required for substantive changes that could impact study conduct, data analysis, or patient safety. Examples include modifying a primary endpoint in the protocol, adding a new risk to an Informed Consent Form, or revising the primary analysis in the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP).

A robust change control process transforms a version number from a simple label into a meaningful record. It demonstrates that every modification was deliberate, reviewed, and documented, creating an unbroken chain of custody for the document’s content.

This systematic approach provides clarity to all stakeholders, from the principal investigator at a clinical site to the auditor reviewing the TMF. When a new version is issued, its significance is immediately understood. For more detail, see our guide on the principles of change control in clinical trial documentation.

The Indispensable Version History Log

To meet regulatory expectations for transparency, every controlled document must include a version history log, typically located at the beginning of the document. This log provides a concise summary of the document's lifecycle and is a foundational element of an auditable record.

A comprehensive version history log must capture the following information for each version:

- Version Number: The specific identifier (e.g., v2.1).

- Summary of Changes: A clear, high-level description of what was modified.

- Rationale for Change: A brief explanation of why the change was necessary.

- Author/Approver: The name(s) of the individuals who made and approved the change.

- Effective Date: The date the new version officially became effective.

This is a standard industry practice. For example, one review of clinical trial documentation found that changes to the SAP were documented in all cases, with many including detailed rationales for the changes, underscoring the commitment to transparency.

Automating Audit Trails with Electronic Systems

While a manual log is a basic requirement, modern electronic document management systems (EDMS) offer a more robust and reliable solution. Such platforms are often designed to meet standards like FDA 21 CFR Part 11, creating immutable, time-stamped audit trails automatically.

These systems log every interaction with a document—including views, comments, edits, and electronic signatures—without manual intervention. This creates a complete, computer-generated history that is more dependable than a manually maintained table. The audit trail becomes an objective record of events, reducing compliance risk and supporting a state of continuous inspection readiness.

Mitigating the Risk of Uncontrolled Document Copies

Even with a sophisticated version control system, its effectiveness is compromised if users work outside the system. A significant operational and regulatory risk in clinical trials is the proliferation of uncontrolled document copies, sometimes referred to as "shadow files."

These are duplicates saved to local desktops, circulated via email, or printed for review. Such actions can systematically undermine a compliant version control strategy. Each uncontrolled copy introduces the risk that personnel will work from an outdated protocol, an obsolete informed consent form, or an unapproved analysis plan. This practice is inconsistent with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and the principles of regulations like ICH E6(R3), which call for reliable, centralized systems to protect trial integrity.

The Operational Impact of Document Duplication

The negative effects of uncontrolled copies extend beyond compliance, creating significant operational inefficiencies. When multiple versions of a document exist, teams must spend valuable time reconciling feedback and verifying which file is the authoritative version.

This administrative burden is a known challenge in clinical operations. Shadow files can create substantial rework, with some analyses suggesting teams spend significantly more time manually reconciling disparate document versions. Uncontrolled documents are a frequent source of regulatory findings. This issue is a high-visibility concern, as detailed in research on the impact of shadow charts from Florence Healthcare.

This disorganization can lead to severe consequences:

- Protocol Deviations: A site may inadvertently follow outdated procedures, leading to inconsistent data collection.

- Timeline Delays: The time required to locate the correct document and consolidate feedback can cause significant delays in document finalization.

- Compromised Data Integrity: Decisions based on incorrect information may call into question the validity of trial data during a regulatory inspection.

Establishing a Single Source of Truth

The most effective way to mitigate these risks is to establish and enforce a single source of truth—a single, central, controlled repository for all official trial documents. This concept is the cornerstone of effective version control best practices for clinical trial documents and requires a combination of appropriate technology, robust processes, and consistent training.

A validated Electronic Document Management System (EDMS) can serve as this central hub. By design, such a system prevents the uncontrolled proliferation of duplicates. It ensures that all stakeholders—from the CRO to the site staff—can only access the current, approved version of any given file.

A single source of truth is not merely a shared folder; it represents a commitment to operational discipline. It ensures that every stakeholder, from the medical writer to the site coordinator, is working from the same official documents, eliminating guesswork and reducing risk.

Practical Steps for Maintaining Document Control

To enforce a single source of truth and eliminate uncontrolled copies, organizations should implement the following strategies. These practices support compliance and help cultivate a culture of disciplined document management.

- Implement Access Controls: Utilize the permission settings within the central system to strictly control who can view, edit, or approve documents. This is a primary defense against unauthorized changes.

- Discourage Local Saving and Printing: Where feasible, configure the system to restrict or disable the downloading or printing of controlled documents. This encourages users to work directly within the validated environment where their actions are tracked.

- Centralize Collaboration: Mandate that all document reviews, comments, and approvals occur within the central platform. This creates a single, complete, and auditable history of feedback, rather than distributing comments across emails and offline files.

- Provide Continuous Training: Regularly reinforce to team members the importance of working from the single source of truth. Training should explain the operational and regulatory risks associated with using uncontrolled copies.

Version Control's Role in Long-Term Archiving

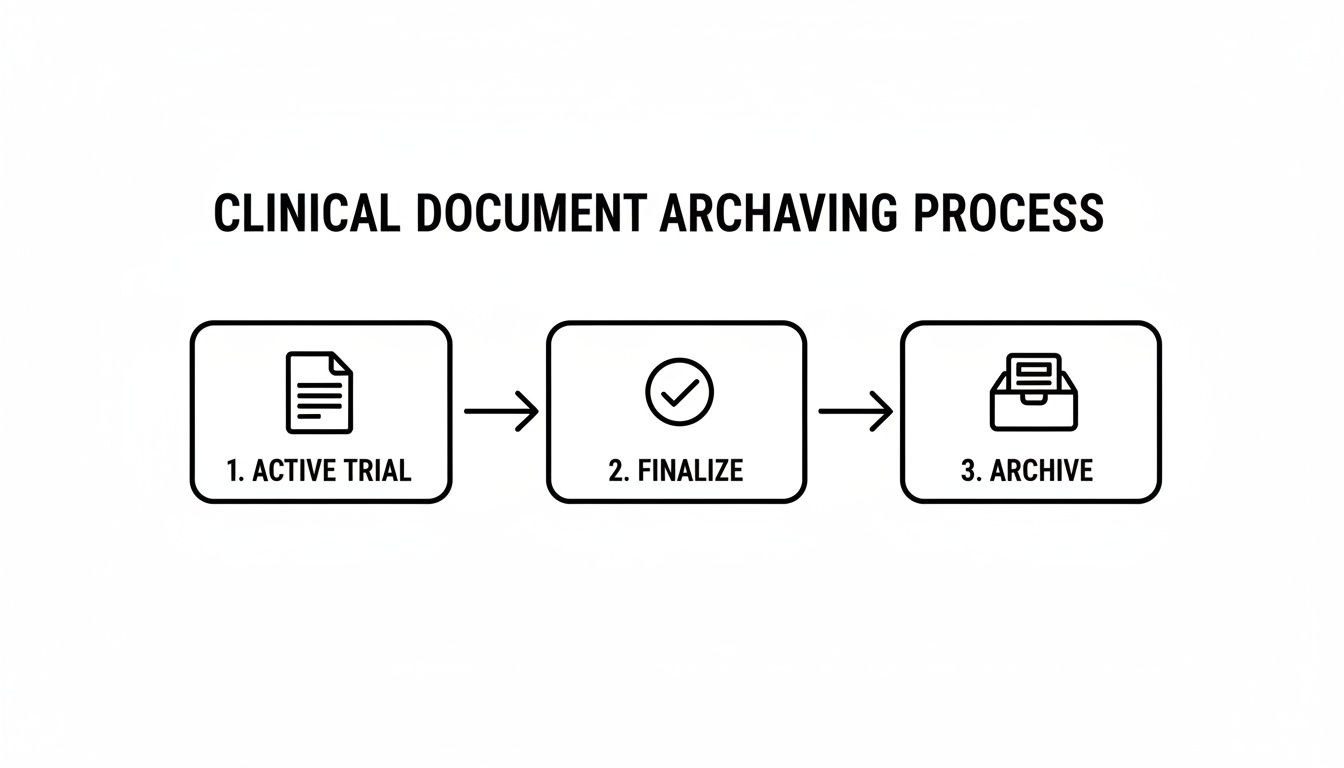

Effective version control is not only for managing active documents but is also a critical prerequisite for compliant, long-term archiving.

Regulatory authorities require that clinical trial records be preserved for many years, sometimes decades, after a study's conclusion. This requirement elevates archiving from a close-out activity to a strategic consideration that must be planned from the outset. This long-term obligation necessitates that documents remain complete, readable, and secure over extended periods. A well-implemented version control system simplifies this process and reduces long-term risk.

Preparing Documents for Long-Term Retention

The objective of archiving is to preserve the final, official record of the trial. Therefore, only the final, approved versions of essential documents should be included in the formal archive. Drafts, superseded versions, and review comments, while part of the document history, should be managed separately from the final TMF content, as defined by SOPs.

To ensure long-term accessibility and integrity, organizations should adhere to these key practices:

- Use Stable File Formats: Convert documents to a format designed for long-term preservation, such as PDF/A (Portable Document Format/Archive). This ISO standard is designed to ensure a file remains visually consistent and accessible for decades, independent of the software used to view it.

- Preserve Metadata: Critical metadata tracked during the trial—including version numbers, approval dates, authors, and e-signatures—must be preserved with the document. This context provides the audit trail an inspector will need to verify the document's history.

- Ensure Read-Only State: Once a document is archived, it must be maintained in a read-only state. This prevents any accidental or unauthorized modifications or deletions, protecting the integrity of the final record.

Addressing Extended Regulatory Timelines

Regulatory requirements for data retention are becoming more stringent, making a clear archival strategy essential. For example, the EU Clinical Trial Regulation 536/2014, which came into full effect on January 31, 2023, mandates a 25-year retention period for TMF data after study completion.

This regulation has global implications, affecting US-based sites and CROs involved in EU trials. Inadequate archiving processes can lead to significant unexpected costs. You can learn more about how this regulation is impacting studies with these insights on new data retention requirements.

A compliant archive is not simply digital storage; it is a time capsule. It must perfectly preserve the final state of trial documentation so that an auditor can reconstruct and understand the study years later. The version control practices implemented today directly determine the quality of that time capsule.

Ultimately, integrating version control processes with an archival strategy creates a seamless flow across the entire clinical trial document lifecycle management process. Proactive planning not only satisfies long-term regulatory obligations but also strengthens the integrity of the clinical trial record for future inspections.

Implementing Version Control in a Compliant Workflow

Integrating version control principles into daily operations transforms them from abstract rules into a practical, audit-ready process. A compliant workflow maps a document's entire journey—from its creation using a controlled template, through collaborative review, to its final approval with legally binding electronic signatures.

This approach should be viewed as building a reliable, repeatable system, which serves as a primary defense against human error and a key to maintaining data integrity. Technology designed with regulatory requirements in mind can enforce these best practices automatically, turning potentially tedious manual tasks into inherent parts of the workflow.

From Creation to Collaboration

The lifecycle of a clinical document should begin with a controlled, pre-approved template, not a blank page. Using a master template for documents like protocols or Investigator’s Brochures ensures that required sections, standard formatting, and the version history log are included from the start. This practice promotes consistency across studies and aligns every new document with organizational SOPs.

Once a draft is created, collaboration begins. A compliant workflow moves this process out of email inboxes and into a controlled environment. Features such as controlled check-in/check-out are essential here. This functionality permits only one user to edit a document at a time, preventing conflicting changes and ensuring the document evolves along a single, traceable path.

Managing Reviews and Approvals Securely

As stakeholders provide feedback, a purpose-built system captures every comment and suggested change directly within the document. This eliminates the error-prone and time-consuming task of manually reconciling feedback from multiple Word files or email threads. The system creates a unified record of all discussions and decisions, building a transparent and complete audit trail.

This high-level workflow illustrates how a document moves from an active state, through finalization, and into a secure, permanent archive.

This structured path is critical. It ensures that only finalized, approved documents are archived, protecting the integrity of the Trial Master File for future inspections.

Following the review cycle, the document is ready for formal approval. This step is governed by specific regulations, such as 21 CFR Part 11 for organizations under FDA oversight.

A compliant electronic signature is not a scanned image of a handwritten signature. It is a cryptographic process that securely links an individual's identity to a document at a specific point in time, along with the stated meaning of the signature (e.g., "author" or "approval"). This creates a legally binding, non-repudiable record of approval.

Modern platforms often integrate compliant e-signature capabilities directly into the workflow. An approval request is routed automatically to the designated individuals. Once they sign, the document is immediately locked to prevent further modification. For more detail on the technical and procedural controls involved, refer to our guide to achieving FDA 21 CFR Part 11 compliance.

Automating Versioning for Audit Readiness

Throughout this lifecycle, a well-designed system should manage versioning automatically. Each time a document is checked in, edited, or approved, the system should assign a new minor or major version number according to pre-defined rules.

This automation provides significant benefits. It eliminates the risk of manual entry errors (e.g., v2.3 instead of v3.2) and ensures a complete, accurate version history is maintained without requiring manual intervention from the team.

An automated, integrated workflow allows clinical operations, medical writing, and regulatory affairs teams to focus on their core scientific and strategic responsibilities rather than administrative tasks. By embedding version control best practices for clinical trial documents directly into daily tools, the entire process becomes compliant by design and perpetually inspection-ready.

Common Questions on Clinical Document Version Control

The following are answers to frequently asked questions regarding the practical implementation of version control in a clinical setting.

What Should We Do With Old Versions of Documents?

When a document is updated, the previous version becomes obsolete. It should not be deleted, as it is part of the trial's official history.

Instead, the superseded version must be immediately removed from active use to prevent inadvertent use. It should then be archived in a secure, designated location for obsolete documents. The file itself should be clearly marked as "Superseded" or "Obsolete." This practice preserves the complete, auditable lifecycle of the documentation, which is required for regulatory review.

What’s the Difference Between a TMF and an ISF?

The Trial Master File (TMF) is the complete set of essential documents for a study, while the Investigator Site File (ISF) contains the essential documents for a specific investigator site.

The TMF is the responsibility of the sponsor or their designated CRO and contains all essential documents from all participating sites. The ISF is maintained by the investigator at their site and includes only the documents relevant to that site's conduct of the trial. While there is significant overlap in content, the TMF provides a comprehensive record of the entire study, whereas the ISF provides the record for a single site.

Is It Okay to Manage All Our Documents Electronically?

Yes, managing documents electronically is standard industry practice. However, the system used must comply with applicable regulatory standards, most notably FDA 21 CFR Part 11 for trials conducted under FDA jurisdiction.

A compliant electronic system is more than a digital filing cabinet. It must include validated security controls, immutable audit trails that log all actions, and capabilities for legally binding electronic signatures. These features are necessary to demonstrate that electronic records are as trustworthy and reliable as their paper-based equivalents.

This ensures the integrity of trial data and maintains accountability.

Who Is Ultimately Responsible for Making Sure Documents Are Ready for an Inspection?

While document readiness is a collective effort, ultimate responsibility is clearly defined. At the individual research site, the Principal Investigator (PI) is responsible for the accuracy, completeness, and maintenance of the ISF.

For the trial as a whole, the sponsor (or a contracted CRO) is accountable for the TMF. While CRAs, medical writers, and quality assurance specialists play key roles in daily management, the final responsibility is assigned. All personnel have a role in maintaining a constant state of inspection-readiness.