Effective clinical study report authoring and version management is a highly structured, auditable process integral to regulatory submissions. The process involves creating, reviewing, and finalizing the definitive account of a clinical trial, demanding a systematic focus on data integrity, transparency, and compliance.

The Regulatory Framework for CSR Authoring and Management

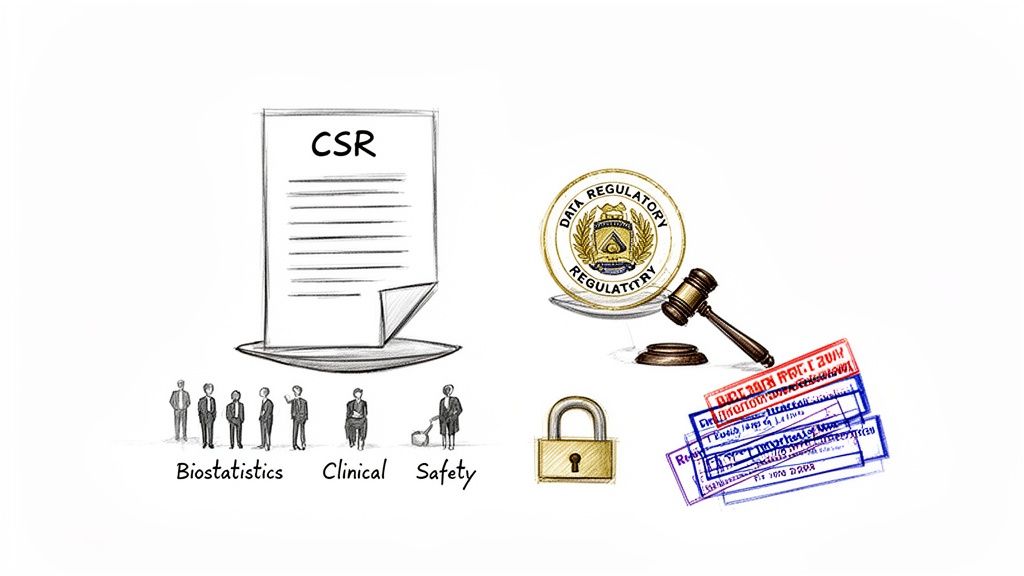

The Clinical Study Report (CSR) is a cornerstone of any regulatory strategy and a testament to a trial's scientific integrity. The focus on structured authoring and meticulous version management reflects global regulatory expectations designed to protect patients and validate trial data. This process is grounded in the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP), making robust documentation a fundamental component of clinical operations.

From Guideline to Standard Practice

The modern CSR was fundamentally shaped by the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), specifically the ICH E3 guidance on the "Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports." This guidance standardized the format of what could otherwise be a simple summary into a comprehensive, data-driven narrative essential for regulatory review. The objective was to harmonize how trial results are presented, enabling agencies like the FDA and EMA to systematically evaluate a product's safety and efficacy.

This standardization has increased the complexity and volume of CSRs. The demands from global regulators have made authoring a significant operational undertaking. It is not uncommon for a single Phase III CSR to undergo numerous distinct draft and review cycles before finalization, incorporating input from clinical, biostatistics, data management, and medical writing teams.

Each of these cycles creates a new version that must be tracked for audit purposes, in alignment with frameworks like ICH E6 (GCP) and principles of electronic record integrity, such as those outlined in FDA 21 CFR Part 11. Consequently, robust version control is a regulatory and operational necessity. More information on the evolution of the modern CSR and its implications is available for further context.

Core Operational Challenges in CSR Development

Producing a CSR involves coordinating contributions from different functional teams, each with distinct priorities and timelines. This requires diligent project management. Without a controlled, systematic approach, teams may encounter common pitfalls that can affect timelines and compliance.

Common operational challenges include:

- Version Proliferation: Uncontrolled drafts distributed via email can lead to confusion regarding the authoritative "master" version. This practice increases the risk of incorporating outdated information or losing critical feedback.

- Comment Adjudication: Reconciling conflicting feedback from multiple reviewers can be time-consuming. For instance, one reviewer may request a section be rephrased for clarity, while another suggests its removal. Without a structured process, review cycles can be prolonged.

- Maintaining a Defensible Audit Trail: It is essential to provide a complete, chronological history of the document's evolution upon request from an inspector. An inability to do so can be a significant finding during a regulatory inspection.

Building a Framework for Compliant CSR Authoring

The preparation for a clinical study report (CSR) begins long before the narrative is drafted. The foundational work involves establishing a deliberate, structured framework to prevent chaotic review cycles, conflicting feedback, and last-minute alignment issues. A well-defined framework is a critical factor in keeping the project on track and ensuring the final CSR is consistent, compliant, and ready for submission.

Establishing Compliant Templates and Shell Reports

The cornerstone of this framework is a robust, ICH E3-compliant template. This is a controlled document that serves as the single source of truth for the CSR's structure. A well-designed template embeds regulatory expectations into the authoring process from the outset.

For example, a template for a Phase III oncology study should have pre-defined sections for the specified primary and secondary efficacy endpoints, safety analyses relevant to the therapeutic class, and subsections for patient-reported outcomes. This ensures that every CSR produced by the organization has a consistent and predictable structure, which aligns with regulatory reviewer expectations.

A well-constructed template does more than ensure compliance; it actively guides the medical writer and cross-functional teams, prompting them to address all necessary components from the outset and preventing critical omissions that could lead to regulatory queries later.

To facilitate preparation, many teams create a CSR shell report before final data are available. This involves populating a master template with known, study-specific information from the protocol and the statistical analysis plan (SAP). This typically includes:

- Study Objectives: Sourced directly from the protocol to ensure alignment.

- Methodology: Key details on trial design, patient population, and treatment schedules.

- Planned Analyses: Placeholders for tables, listings, and figures (TLFs) outlined in the SAP.

This proactive step transforms the CSR from a blank document into a structured, partially-completed report awaiting final data, which can accelerate the drafting process after database lock.

Defining Roles and Responsibilities

Undefined roles and responsibilities can impede a CSR project. Clarifying ownership and review assignments upfront is essential. This is typically formalized in a CSR Authoring Plan, which maps out who is responsible for authoring, reviewing, and approving each section of the report.

For example, the biostatistics team is responsible for generating TLFs, while the medical writer is responsible for authoring the narrative that interprets them. The clinical team then reviews that narrative for medical accuracy and clinical context. A clear plan defines these handoffs, dependencies, and review expectations, preventing feedback from being provided by the wrong functional area or at an inappropriate time.

Key Components of a CSR Authoring Plan

This table outlines essential elements to define before starting a CSR, ensuring alignment across all functional teams.

| Component | Purpose and Key Considerations | Example Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| Section Ownership | Clearly assigns a lead author and primary reviewer(s) for each major CSR section (e.g., Intro, Methods, Efficacy, Safety). | Medical Writer authors Safety narrative; Clinical Scientist is the primary reviewer. |

| Review Timelines | Sets realistic deadlines for each review cycle (e.g., Draft 1, Draft 2, Final). Considers dependencies between sections. | 5-7 business days for Draft 1 review by the core team. |

| Key Contributors | Lists all stakeholders (Biostats, ClinOps, Regulatory, PK/PD) and their specific contributions. | Biostatistics team provides final TLFs and reviews their interpretation. |

| Comment Adjudication | Defines the process for resolving conflicting feedback. Establishes a final decision-maker (e.g., Lead Clinician). | Medical Writer compiles all comments; a consensus meeting is held to resolve conflicts. |

| Version Control Naming | Specifies the exact naming convention for all drafts (e.g., "CSR_Protocol123_DRAFT_v0.1_YYYY-MM-DD"). | Protocol Number + Document Status + Version + Date. |

| Final Approval | Outlines the sequence of sign-offs required for the final, submission-ready CSR. | Final sign-off by Head of Clinical Development and Head of Regulatory Affairs. |

Defining these elements in writing removes ambiguity and enables team members to work efficiently toward a common goal.

Proactive Planning and Content Mapping

Successful CSR projects often involve proactive content mapping. This is the exercise of systematically linking specific sections of source documents—the protocol and the SAP—to their corresponding destination in the CSR template.

For example, the inclusion/exclusion criteria from the protocol are mapped directly to the "Study Patients" section. The primary endpoint analysis described in the SAP is mapped to the "Efficacy Results" section. This creates a clear roadmap for content development.

Conducting this mapping exercise early also serves as a gap analysis, helping the team identify discrepancies or areas requiring clarification well before submission deadlines. Ensuring foundational documents are aligned with the planned CSR structure helps eliminate surprises and contributes to a smoother authoring process.

Implementing Structured Drafting and Review Workflows

With a solid framework in place, the iterative process of writing and reviewing the clinical study report can begin. This phase is where the narrative is developed, raw data is interpreted, and the cross-functional team collaborates to build the final document. A controlled, auditable workflow is essential to avoid version chaos and untraceable changes.

Decentralized approaches, such as exchanging Word documents via email, make it difficult to identify the authoritative version, reconcile conflicting feedback, and maintain a clear audit trail. A more structured process is recommended, beginning with a controlled template and clear roles to establish a robust plan.

This process flow illustrates that a successful workflow is built upon the foundational elements of a controlled template, clearly assigned roles, and a detailed authoring plan.

Adopting a Phased Review Process

A phased review approach can bring order and efficiency to the process. By breaking the review into logical stages, relevant experts provide feedback at the appropriate time. This sequential process can reduce redundant comments and conflicting suggestions that may arise when all reviewers provide input simultaneously.

A typical phased review workflow may include:

- Initial Functional Review: The first draft, or specific sections, is distributed to relevant functional leads. For example, the biostatistics team reviews the results sections and TLF interpretations, while the clinical team focuses on the medical narrative and safety discussions.

- Cross-Functional Alignment: After individual sections are reviewed, a consolidated draft is circulated to the broader core team to check for consistency and alignment across the entire document. The objective is to ensure a logical flow from methods to results to conclusions.

- Final Quality Control (QC) and Approval: The near-final CSR undergoes a meticulous QC check. This involves verifying data against source TLFs, checking for grammatical and formatting errors, and confirming alignment with the ICH E3 structure and internal style guide. The document is then routed for final sign-off.

Managing Feedback and Resolving Comments

Systematic feedback management is a cornerstone of effective clinical study report authoring and version management. A common challenge is adjudicating conflicting comments, such as when a statistician and a clinician propose different interpretations of a result.

The purpose of a structured review is not to eliminate debate, but to channel it productively. A formal comment resolution process ensures every piece of feedback is considered, dispositioned, and documented, creating an auditable record of the team's decisions.

Effective feedback management often utilizes a central repository for all comments, such as a document management system or a collaborative platform. This avoids the manual consolidation of feedback from multiple annotated documents. The lead medical writer typically facilitates a comment resolution meeting where conflicting points are discussed and a final decision is made by a designated authority, such as the lead clinical scientist. Further details on this topic are available in a guide on document review and approval workflows in clinical trials.

Real-World Scenario: Incorporating Statistical Feedback

Consider a scenario where a medical writer receives feedback on a CSR draft from the biostatistics team. A statistician comments on a key efficacy table, noting that while the p-value for the primary endpoint is statistically significant, the confidence interval is wide, suggesting a high degree of variability.

Simply stating the p-value in the text is insufficient. The writer needs to incorporate this nuance into the narrative.

- Initial Text: "Treatment with Drug X resulted in a statistically significant improvement in the primary endpoint (p<0.05)."

- Revised Text with Feedback: "Treatment with Drug X resulted in a statistically significant improvement in the primary endpoint (p=0.042). While the primary endpoint met statistical significance, the 95% confidence interval [X.X, Y.Y] indicates considerable variability in patient response, a factor that is further explored in the subgroup analyses."

This revision provides critical context for the reader and sets the stage for a deeper discussion later in the CSR. Each change should be captured using a "track changes" feature, and the rationale for accepting the comment should be noted in a comment resolution log. This creates a clear, traceable history of how the data interpretation evolved, demonstrating a thoughtful and controlled authoring process.

Version Control and Change Management

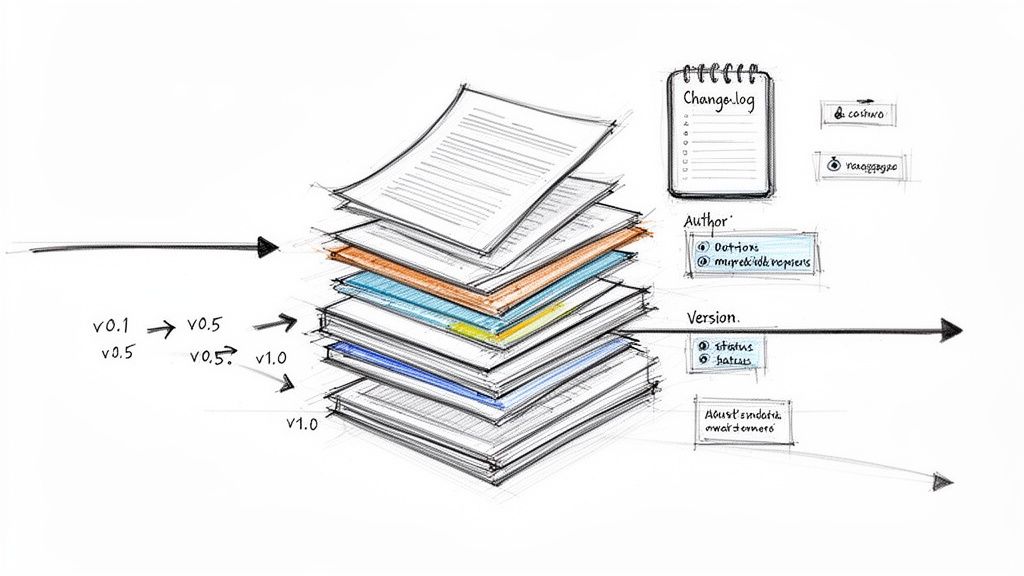

Robust version management provides the technical backbone for a compliant clinical study report. It is more than saving files with different names; it involves creating an auditable, chronological history that demonstrates to regulators that the document evolved in a controlled, deliberate, and traceable manner. The integrity of the CSR and the data it represents depends on this discipline.

This system is built on clear conventions, detailed change logs, and managed document metadata, all housed within a controlled environment. These practices are linked to regulations like 21 CFR Part 11, which call for secure, time-stamped audit trails for electronic records.

Establish Clear Versioning Conventions

A standardized versioning convention is the first line of defense against document disorganization. It provides an immediate, at-a-glance understanding of a document’s status and maturity. Consistent application of a logical system helps prevent teams from working on outdated drafts or submitting an incorrect version for review.

A common approach to versioning includes:

- Minor Versions (e.g., v0.1, v0.2): Used for iterative changes during initial drafting by the lead author or a small group of contributors as they incorporate data or refine the narrative.

- Major Versions (e.g., v1.0, v2.0): Mark significant milestones, typically corresponding to formal review cycles. Version 1.0 would be the first complete draft for cross-functional review, and Version 2.0 would be the revision incorporating that feedback.

- The Final Version (e.g., v1.0_FINAL): This designation is reserved for the single approved and electronically signed CSR ready for submission. Once a version is final, its content is locked.

The Change Log: The Document's History

A detailed change log is as critical as the version number. It is a human-readable summary of the audit trail, explaining the rationale behind each significant revision. A comprehensive change log documents what was changed, who requested it, why it was necessary, and when it occurred.

A change log is not just a list of edits; it is the scientific and operational history of your document. To an inspector, it demonstrates that every decision was thoughtful, controlled, and recorded transparently.

Maintaining this log within a document management system or at the beginning of the CSR ensures this critical history remains with the report. This is a foundational practice for compliant change control in clinical trial documentation.

A pivotal phase III CSR can take from 3 to 6 months to complete after database lock, involving significant medical writing and review time. By adopting structured authoring methods that rely on robust version management, teams may be able to shorten these timelines and reduce costs.

Managing Post-Finalization Changes

In clinical trials, new data may emerge or a regulatory agency may request a re-analysis after a CSR has been finalized. The finalized document cannot be reopened and edited, as this would break the signature and invalidate the audit trail.

Such situations are managed through formal, controlled documents:

- CSR Addendum: Used to provide new information that was not available when the main CSR was finalized, such as results from a long-term patient follow-up study.

- CSR Amendment: Required for changes that fundamentally alter the interpretation or conclusions of the original, finalized CSR. It corrects, clarifies, or modifies the report and is used less frequently than an addendum.

Both addenda and amendments are separate documents that undergo their own authoring, review, and approval cycles, each with its own versioning (e.g., "CSR Amendment 1_v1.0_FINAL").

The Role of Metadata

Metadata provides essential context for every version of the CSR stored within an Electronic Document Management System (EDMS).

Key metadata fields include:

| Metadata Field | Purpose and Importance | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Document Title | Uniquely identifies the report, usually with the protocol number. | CSR for Protocol XYZ-123 |

| Version Number | Follows your convention (v0.1, v1.0) for instant status recognition. | v2.1 |

| Status | Shows where the document is in its lifecycle (Draft, In Review, Approved). | In Review |

| Author(s) | Records who created and revised the content. | J. Smith, A. Patel |

| Date | Timestamps creation, modification, or approval for a clear audit trail. | 2024-10-26 |

Structured metadata ensures that every version of the CSR is identifiable and traceable within the EDMS, forming the foundation of a defensible, inspection-ready document history.

Ensuring the CSR is Submission-Ready and Audit-Proof

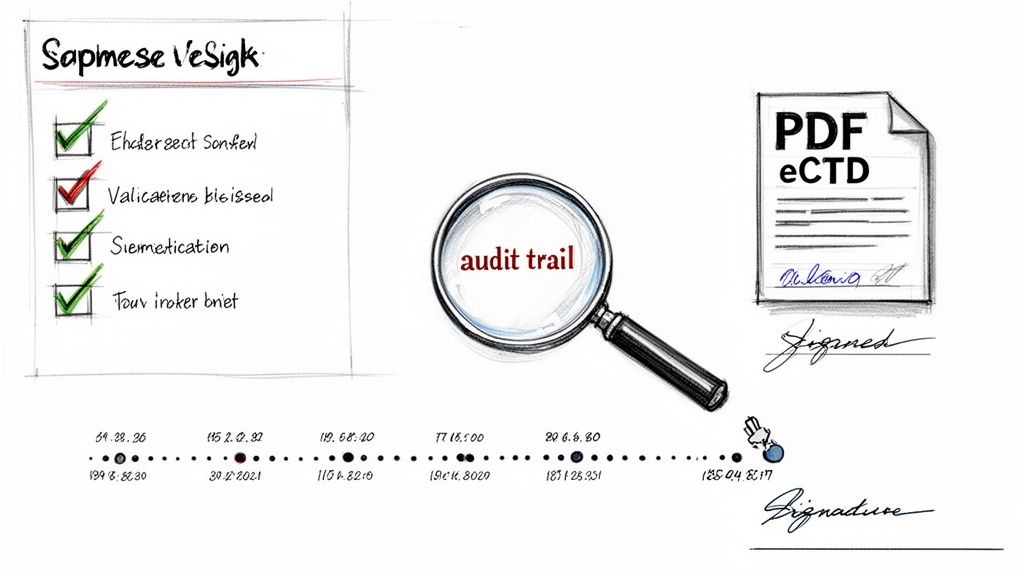

The final phase of CSR development involves preparing a document that can withstand regulatory scrutiny. This stage is a comprehensive validation of the entire process, where the careful steps taken earlier converge into a single, high-quality, and defensible report.

Running Comprehensive Quality Control Checks

Before a document is finalized, it must undergo a rigorous quality control (QC) process. This involves a deep, systematic verification of every claim and number in the report against the source data.

A dedicated QC specialist focuses on:

- Data Verification: Cross-checking every key data point, statistical result, and patient number in the text against the final tables, listings, and figures (TLFs).

- Internal Consistency: Ensuring the synopsis aligns with the main body and the conclusions accurately reflect the data presented.

- Regulatory Adherence: Confirming the report’s structure and content strictly follow ICH E3 guidelines and any other region-specific requirements.

- Template and Style Guide Compliance: Checking that all formatting, terminology, and abbreviations align with the approved company style guide and CSR template.

Preparing the Submission-Ready Document

After QC is complete and the content is locked, the report is rendered into the required electronic submission format, typically a PDF. This document must meet the technical specifications for the electronic Common Technical Document (eCTD).

Generating a submission-ready PDF is a technical process. An improperly constructed file could be rejected by an agency’s electronic gateway on a technicality before a scientific reviewer sees it.

Critical technical preparations include:

- Hyperlink Validation: Every internal cross-reference and external link to an appendix must function correctly.

- Bookmark and TOC Generation: The PDF requires a clean, navigable table of contents and a bookmark structure that mirrors the ICH E3 framework to help reviewers navigate the document efficiently.

- PDF Specification Adherence: The file must comply with the specific PDF versions and settings mandated by the FDA, EMA, or other regulatory bodies.

The Final Step: Electronic Signatures and the Audit Trail

Final approval is documented through electronic signatures, which are secure, legally binding attestations compliant with regulations like FDA 21 CFR Part 11.

A compliant e-signature system is based on three core principles:

- Authentication: It verifies the identity of the signer.

- Integrity: It locks the document, preventing alteration post-signature.

- Non-repudiation: The signer cannot later deny their approval.

From the first draft to the final signed version, the process creates a comprehensive audit trail. This is a defensible, time-stamped history of every action taken on the document: who changed what, when it was done, and who provided final approval. A deeper overview of FDA 21 CFR Part 11 compliance provides more specifics on these requirements.

During an inspection, this audit trail provides evidence that the CSR was developed under controlled, documented, and compliant conditions.

Looking Ahead: Future-Proofing CSR Authoring

A well-defined process for clinical study report authoring and version management is a strategic asset. A systematic approach based on solid templates and controlled workflows is the foundation for maintaining scientific accuracy, data integrity, and regulatory compliance.

While the core principles of planning and version control are enduring, the tools used to implement them continue to evolve. As trial designs become more complex and data volumes increase, reliance on manual processes becomes less sustainable.

Adopting a Strategic Documentation Mindset

Organizations can benefit from treating their CSR development process as a core competency. The CSR is the official record of a clinical trial, and its quality reflects on the sponsor. A well-planned, systematic process can transform a resource-intensive task into a predictable and efficient engine for successful regulatory submissions.

A proactive, well-documented, and controlled approach to CSR development is not a burden but a strategic advantage that can lead to more efficient, dependable, and successful filings with regulatory agencies.

This shift in mindset ensures each CSR is an accurate, defensible, and high-quality document that effectively communicates the trial's scientific story. Building these principles into team operations lays a foundation for long-term success, providing the confidence to manage growing complexity and ensure every submission can withstand rigorous scrutiny.

Frequently Asked Questions About CSR Management

Practical questions often arise during the process of writing and managing a clinical study report. The following sections address some of the most common issues encountered by teams.

What is the difference between a CSR draft and the final version?

A CSR "draft" is a working document used internally for collaboration, review, and development. These versions, often marked as v0.1 or v0.2, are intended to be modified.

The "final" version is the official, locked document, typically designated as v1.0 after all internal reviews and approvals are complete. It has undergone a rigorous quality control process, is electronically signed, and is prepared for regulatory submission. Its content is fixed. Any subsequent changes require a formal addendum or amendment, each with its own version control.

This distinction is important for the audit trail. Regulators expect to see a clear history of how the document evolved from early drafts to the final, locked version that becomes part of the official trial record.

How can input from multiple contributors be managed effectively?

Managing contributions from statisticians, clinicians, project managers, and quality assurance requires a centralized system. The key is to have a single source of truth, such as a dedicated document management system or a collaborative authoring platform, to avoid version chaos.

Assigning a lead author, typically a medical writer, to serve as the central hub for integrating all feedback is a common best practice. A sequential workflow can also be effective. For example, the biostatistics team can finalize the results sections first, after which the clinical team provides interpretation and context. This prevents contributors from making simultaneous, potentially conflicting edits.

It is advisable to avoid exchanging uncontrolled Word documents via email. This practice can lead to lost feedback, confusion over the current version, and a compromised audit trail. A system that tracks every change and comment is recommended.

What are the essential components of an ICH E3-compliant CSR template?

An ICH E3-compliant CSR template provides the structure that regulators use to navigate the study's report. Aligning the template with this guidance is a fundamental step.

Non-negotiable elements for the template include:

- Core Components: A Title Page, Synopsis, and a detailed Table of Contents.

- Administrative and Ethical Sections: Sections on Ethics and the study's Administrative Structure, documenting IRB/IEC approvals and listing key personnel.

- Study Plan: A full breakdown of the Investigational Plan, covering study design, patient population, treatments, and efficacy and safety measurements.

- Patient Accountability: Clear accounting for all Study Patient Disposition and their demographics.

- Results: The Efficacy and Safety Evaluation sections, presenting all results and analyses.

- Interpretation: A Discussion and Overall Conclusions section for interpreting the findings and presenting the risk-benefit assessment.

- Appendices: Appendices that include the protocol, sample case report forms, statistical methods, and patient data listings.

A well-designed template not only lists these sections but may also include placeholder text and instructional notes to guide authors, ensuring all required components are addressed consistently across studies.