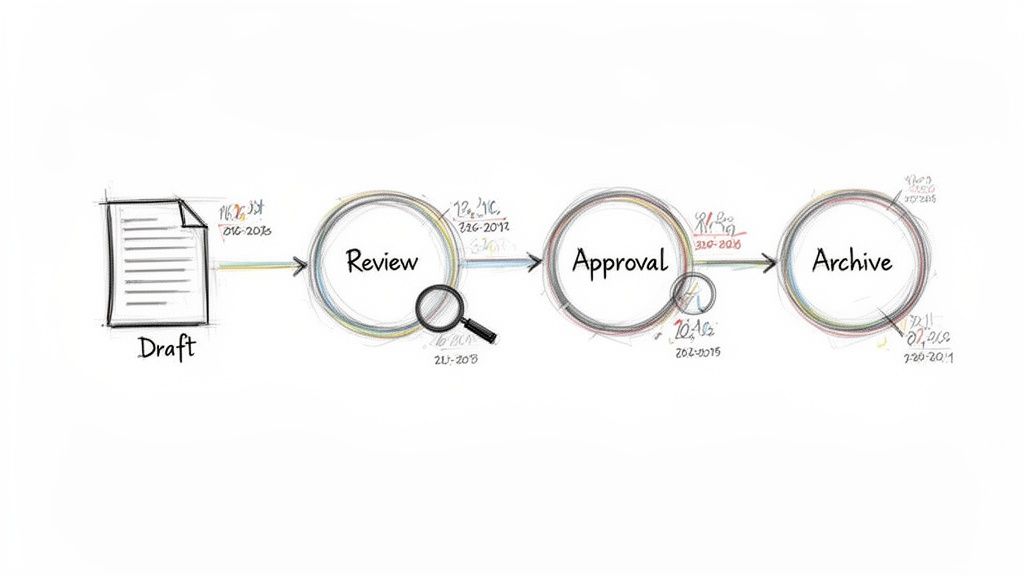

Document traceability is the complete, verifiable history of a clinical trial document. It encompasses the entire lifecycle, from the initial draft to the final archived version, capturing every change, review, and approval. This creates an auditable record that demonstrates the integrity of study documentation.

The Foundation of Document Traceability

In a clinical trial, documents are not static files; they are dynamic records that evolve as the study progresses. Traceability allows stakeholders and inspectors to reconstruct that evolution and answer critical questions: Who authored the protocol? What was the rationale for a specific amendment? How was a reviewer’s comment on a draft Clinical Study Report (CSR) resolved in the final version?

This record provides a detailed history connecting each decision to a specific action and outcome. For example, a robust traceability system can link a comment from a medical reviewer on a draft protocol directly to the revised text in the final, IRB-approved version.

This interconnected history is fundamental to the scientific integrity of a clinical trial. It provides evidence that the study was conducted according to a controlled, documented plan and ensures that the results reported in the CSR are a direct consequence of the scientific objectives defined in the protocol.

Where Traceability Matters Most: Core Clinical Trial Documents

While all study documentation requires a clear history, traceability is particularly critical for the core documents that define and report on the trial:

- Clinical Trial Protocol: The foundational document detailing the study's objectives, design, methodology, and statistical considerations.

- Investigator’s Brochure (IB): A comprehensive summary of clinical and nonclinical data on the investigational product.

- Informed Consent Form (ICF): The document explaining the trial to potential participants, which must align with the currently approved protocol.

- Clinical Study Report (CSR): The final report presenting the complete results and analysis of the study.

Effective traceability ensures the scientific narrative flows logically and consistently from the protocol through to the CSR, with every step accounted for.

Why Regulators Demand Traceability

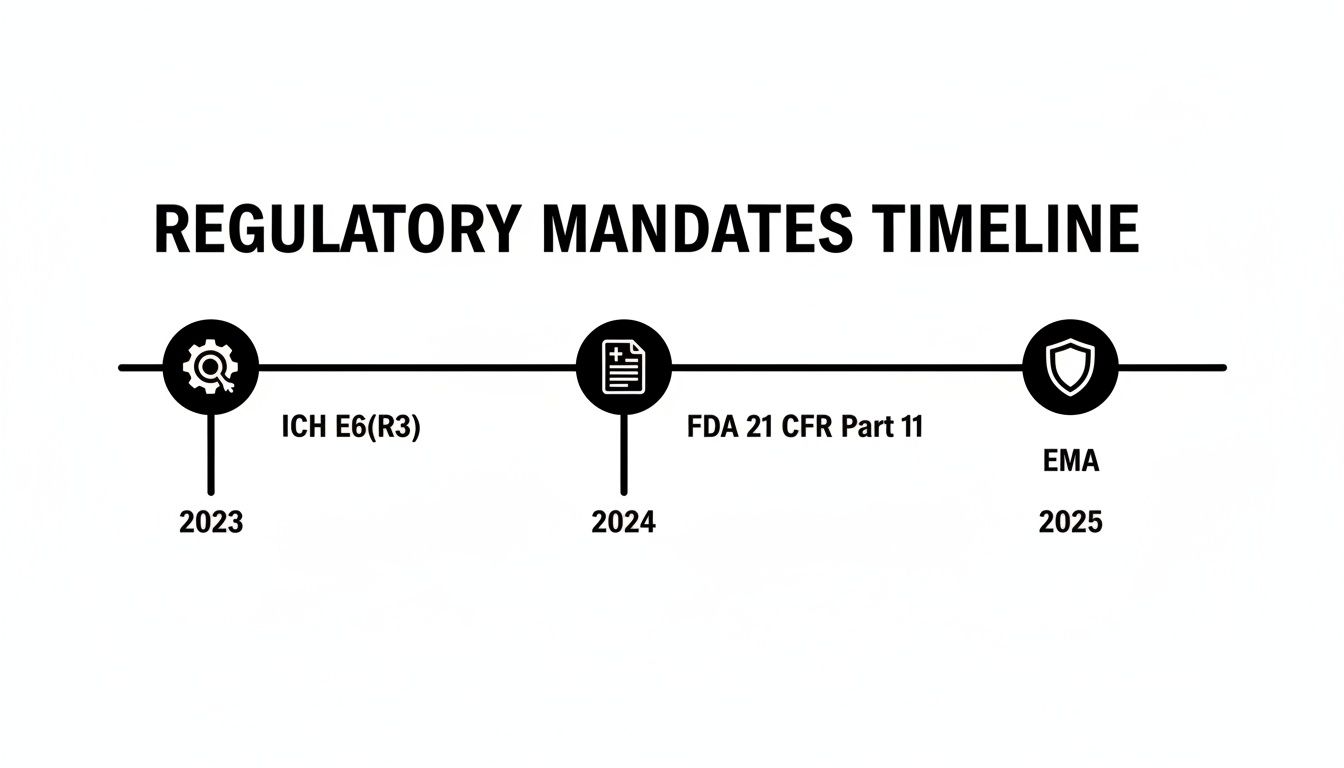

For regulatory bodies such as the FDA and EMA, traceability is a fundamental component of Good Clinical Practice (GCP). It is the primary means for inspectors to reconstruct how a trial was conducted, which is essential for verifying patient safety and data integrity.

Regulatory frameworks, including the FDA's 21 CFR Part 11 and ICH E6(R2), are predicated on the principles of comprehensive audit trails and traceability. GCP requires that decisions, data points, and changes in trial documentation—from protocols and ICFs to CSRs—be traceable to their source. This involves maintaining secure logs with timestamps, author identification, and clear version controls. Inadequate metadata or an incomplete change history are common audit findings that can impact a regulatory submission. Further information on this topic is available in resources covering audit trails in clinical data management.

Without a clear, unbroken chain of evidence, a sponsor cannot adequately demonstrate that a study followed the approved protocol or that the resulting data are reliable. This makes document traceability across the clinical trial lifecycle an essential element of inspection-readiness.

To build a compliant system, it is helpful to understand its core components. Each plays a specific role in creating a complete and defensible document history.

Core Components of Document Traceability

| Component | Description | Regulatory Rationale (ICH E6, 21 CFR Part 11) |

|---|---|---|

| Versioning | A systematic method of assigning unique identifiers (e.g., v1.0, v2.1) to each iteration of a document. | Ensures that only the current, approved version of a document is in use, a key principle of GCP (ICH E6 4.9.4). Prevents the use of outdated protocols or ICFs. |

| Audit Trails | A secure, computer-generated, time-stamped log that records the "who, what, when, and why" of every action. | Directly addressed by 21 CFR Part 11.10(e). Provides objective evidence needed to reconstruct events and demonstrate data integrity. |

| Change History | A human-readable summary of changes made between versions, often explaining the rationale for significant updates. | Supports the audit trail by providing context. This is crucial for understanding amendments and justifying deviations (ICH E6 5.5.3). |

| Metadata | Descriptive data about the document, such as author, creation date, status (draft, final), and effective date. | Essential for document management and control. 21 CFR Part 11 requires that electronic records be retrievable and protected, which relies on accurate metadata. |

| Reviewer Accountability | Clear records linking specific feedback, comments, and approvals to individual reviewers and their roles. | Demonstrates that the review and approval process was controlled and involved qualified individuals, aligning with ICH E6 quality management principles. |

Together, these elements form a system that not only addresses regulatory requirements but also provides a clear, logical, and defensible history of every critical document in a clinical trial.

Why Traceability Is a Regulatory Mandate

Document traceability is an integral part of conducting a clinical trial. Global regulators like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) view a traceable document trail as primary evidence that a study was conducted ethically, scientifically, and with a focus on patient safety and data integrity.

To an inspector, the documentation represents the trial itself. If a decision, action, or amendment is not documented with a clear, auditable history, its occurrence cannot be verified. Inspectors use traceability to reconstruct the study from inception to completion, confirming that the trial described in the final Clinical Study Report (CSR) aligns with the one defined in the initial protocol.

Aligning Operations with Regulatory Intent

The purpose of regulatory guidelines is to establish a framework that ensures quality and safety, not to prescribe specific software or operational models. When sponsors and CROs understand the rationale behind the regulations, they can design internal processes that are inherently compliant.

Several key guidelines inform current traceability expectations:

- ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice: The latest revision emphasizes proactive, risk-based quality management. For documentation, this means traceability must demonstrate that processes were designed to protect critical aspects of the trial. It involves connecting the study's design and execution—as captured in documents—to a well-defined plan for managing risks.

- FDA 21 CFR Part 11: This regulation provides the criteria for trustworthy and reliable electronic records and signatures. It requires controls such as secure audit trails and strict access management. More information on the required controls is available in our FDA 21 CFR Part 11 compliance in our detailed guide.

- EMA Guidelines: The EMA places significant emphasis on data and system integrity. Its guidance consistently calls for a complete, contemporaneous, and attributable audit trail to ensure the full history of every document and data point can be reconstructed.

Ultimately, these regulations converge on a central principle: the ability to prove what happened, when it happened, who performed the action, and why.

The Inspector's Perspective on Traceability

A regulatory inspector uses traceability to connect disparate elements across the entire trial, verifying adherence to the core principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP).

An inspector may perform checks such as these:

- Confirming Protocol Adherence: Selecting a patient's record and tracing their participation back to the specific version of the protocol that was active at the time of their enrollment.

- Verifying Informed Consent: Checking that the Informed Consent Form (ICF) a patient signed corresponds exactly to the IRB-approved version associated with that protocol. Any discrepancy is a significant finding.

- Validating Data in the CSR: Taking a key endpoint from a table in the final CSR and tracing it back to the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and, subsequently, to the source data in the clinical database.

The ultimate goal for a regulator is to confirm the scientific narrative is sound. They must be able to see an unbroken, logical line from the study's original scientific question in the protocol, through its execution and data collection, to the final conclusions presented in the CSR. Any gap in this narrative undermines the trial's credibility.

Without this complete, demonstrable history, the integrity of trial data may be questioned, potentially affecting the entire regulatory submission. Building robust document traceability is therefore about protecting the scientific validity of the research itself.

Where Traceability Fits Into the Clinical Trial Lifecycle

Document traceability should be viewed not as a discrete task, but as a continuous process integrated into every stage of a clinical trial, from initial concept to final report. Mapping traceability to specific milestones transforms it from a retrospective exercise into a real-time quality management tool.

This proactive approach ensures every document is linked as the trial unfolds, creating a chain of evidence that can withstand regulatory inspection.

Study Design and Protocol Development

The process begins with the protocol, the blueprint for the entire study. The objective at this stage is to create a clear, logical path from the scientific question to the study's endpoints.

Every endpoint, primary or secondary, must tie directly to a specific study objective. From there, a verifiable link is required to the statistical methods defined in the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP). This ensures the statistical plan is designed to answer the questions posed by the protocol.

Traceability at this stage functions as a quality control measure. It confirms that the scientific "question" (the protocol objective) and the "answer" (the SAP) are aligned, preventing mismatches that could compromise the study.

Document Drafting and Review Cycles

As the protocol, Investigator's Brochure (IB), and other key documents are developed, traceability shifts to managing change. This phase focuses on capturing the rationale behind each decision. Every comment from a medical monitor, suggestion from a statistician, and revision from regulatory affairs must be recorded and linked to its resolution.

This creates a defensible audit trail. For instance, a reviewer's concern about an inclusion criterion should be traceable to the exact wording change in the subsequent version of the protocol. This demonstrates a controlled and thoughtful decision-making process, a cornerstone of Good Clinical Practice (GCP).

The regulatory environment continues to evolve, adding to the importance of well-defined processes.

Evolving regulations require that systems for managing electronic records and quality are not only compliant today but are prepared for future requirements.

Trial Execution and Amendments

Once the study is active, traceability supports operational consistency and amendment control. The most critical link is between the approved protocol and the Informed Consent Form (ICF) used at clinical sites.

The study team must be able to prove that every participant was consented using the IRB-approved ICF version corresponding to the protocol active at that time. A break in this chain is a significant compliance risk and can lead to the invalidation of patient data.

When a protocol amendment is implemented, the traceability network expands. The amendment must be linked to all impacted documents:

- The updated ICF distributed to sites.

- Revised pharmacy manual procedures.

- Necessary changes to the SAP.

- All corresponding records in the Trial Master File, creating a complete record of the change.

Data Lock, Analysis, and Reporting

This is the final validation of the traceability system. During the final stages of the trial, every number, table, and figure in the Clinical Study Report (CSR) must be fully traceable to its source.

This creates an unbroken path from a conclusion back to the raw data. For example, a p-value in a CSR efficacy table must trace back to a specific analysis in the final, locked SAP. That analysis, in turn, points to a dataset that can be verified against the locked clinical database. This end-to-end connection demonstrates that the study's conclusions are the direct result of the predefined plan.

Traceability Checkpoints in the Clinical Trial Lifecycle

The table below outlines where critical traceability actions occur throughout the trial, mapping key documents and required actions at each phase, along with potential consequences of failure.

| Trial Phase | Key Document(s) | Critical Traceability Action | Potential Risk of Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design & Protocol Dev | Protocol, Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) | Link scientific objectives to endpoints, and endpoints to specific statistical methods in the SAP. | Misaligned study design; inconclusive results; protocol questions from regulators. |

| Document Drafting & Review | Protocol, Investigator's Brochure (IB), ICF | Connect reviewer comments to specific version changes, creating a full change history and decision log. | Inability to defend changes during an audit; delays in document finalization. |

| Trial Execution & Amendments | Approved Protocol, ICF, TMF | Verify that the ICF version used for each patient matches the active protocol; link amendments to all impacted documents. | Major GCP compliance findings; patient data invalidated; patient safety risks. |

| Data Lock, Analysis & Reporting | Clinical Database, SAP, Clinical Study Report (CSR) | Trace every result in the CSR (tables, figures) back to the final SAP and the locked analysis datasets. | Rejection of regulatory submission; challenges to data integrity and study conclusions. |

This meticulous mapping builds a credible, defensible, and successful regulatory submission.

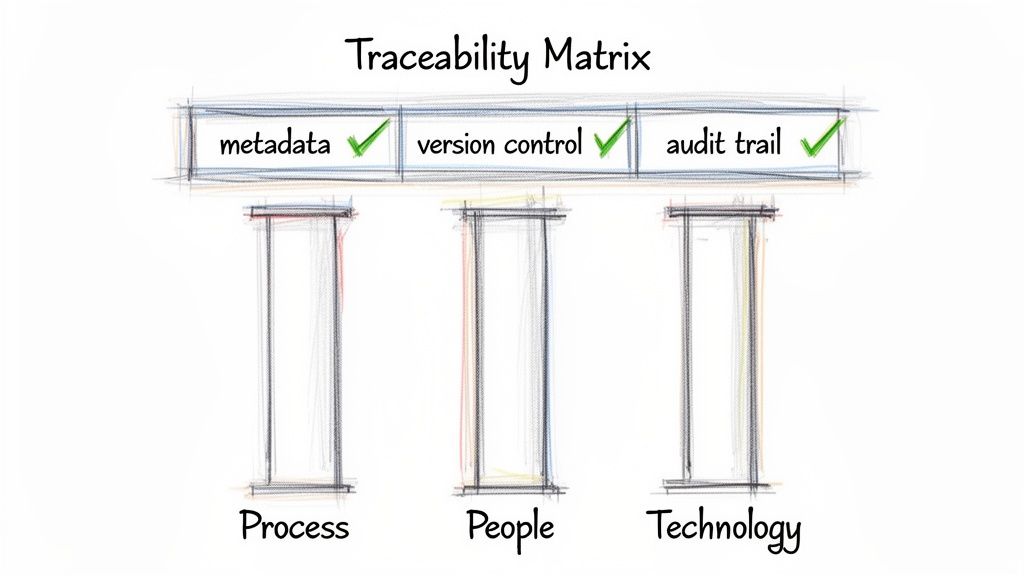

Building a Framework for Reliable Traceability

Establishing a robust traceability framework is not about selecting specific software, but about embedding systematic processes into daily operations to create a documentation ecosystem that can withstand scrutiny. It involves moving from manual tracking toward a systematic approach.

This is accomplished by integrating traceability matrices, consistent metadata, strict version control, and compliant audit trails into document preparation and review workflows.

Using Traceability Matrices

A traceability matrix is a tool that creates explicit connections between related requirements across different documents. This is essential for maintaining scientific integrity from the protocol through to the final report.

For instance, a well-structured matrix will:

- Link Protocol to CSR: Every scientific objective in the protocol is mapped to its corresponding endpoint, the relevant analysis in the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP), and the specific table or figure in the Clinical Study Report (CSR).

- Track Amendments: When a protocol amendment occurs, the matrix identifies all downstream documents that are impacted, ensuring the Informed Consent Form (ICF) and other materials are updated accordingly.

The result is a bidirectional linkage. An auditor can point to any result in the CSR, and the study team can trace it back to the originating scientific question in the protocol.

Establishing Consistent Metadata Standards

Metadata—the data about documents—is a critical component of an audit-ready Trial Master File (TMF). Inconsistent metadata can make it difficult to reconstruct events or demonstrate control. Establishing firm standards is therefore non-negotiable.

A robust metadata standard ensures every document is tagged with essential information: a unique ID, version number, status (e.g., Draft, In Review, Final), author, approvers, and effective date. This structure transforms an eTMF from a simple repository into a searchable and defensible system.

Without these standards, teams often resort to inconsistent file-naming conventions, which can obscure critical information. Consistent metadata is also the foundation of effective clinical trial document lifecycle management, providing control from creation to archival.

Implementing Strict Version Control

Clear version control is the only way to distinguish between a draft and the final, approved document that governs trial conduct. A reliable system ensures that only the current, effective version of a document—be it the protocol or an ICF—is accessible to clinical sites.

The process must be systematic, typically using a major/minor versioning scheme (e.g., v1.0 for a major release, v1.1 for a minor revision). Every new version must be accompanied by a change history that explains what was changed and why, adding necessary context to the audit trail.

Defining Compliant Audit Trails

A compliant audit trail is more than a simple activity log. It is a secure, computer-generated, time-stamped, and unalterable record. Regulators expect it to capture the "who, what, when, and why" for every critical action.

This means every view, edit, comment, signature, and status change is logged with:

- Who: The unique user who performed the action.

- What: A description of the event (e.g., "Approved Document," "Added Comment").

- When: A system-generated, non-modifiable timestamp.

- Why: The reason for a change, where applicable (e.g., "Revised per FDA feedback").

The impact of such structured systems is significant. A study in JAMA Network Open found that traditional, manual traceability methods had a success rate of only 11.5%. In contrast, when advanced, structured systems were used, the success rate increased to 77.3%. This highlights the importance of modern frameworks for meeting current standards.

Common Traceability Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Achieving effective document traceability is essential, but operational gaps can undermine the system. These issues often begin as minor inconsistencies that accumulate over time, creating significant compliance risks that are difficult to resolve during an inspection. Identifying and addressing these weak points is the first step toward building a resilient documentation process.

Inconsistent Naming Conventions and Metadata

A common problem is the lack of standardized file naming. File names like Protocol_v2_FINAL_rev_JSmith.docx make it impossible to determine the authoritative version, complicating any attempt to reconstruct a document’s history.

The solution requires discipline: create and enforce a strict naming convention through a standard operating procedure (SOP). The file name should convey key information, including the document type, version, and status (e.g., DRAFT, FINAL). This simple change improves clarity and simplifies TMF management.

Reliance on Manual Approval Processes

Using email for document review and approval is a significant vulnerability. Email chains are not a reliable mechanism for traceability. An inspector cannot follow a fragmented conversation across multiple inboxes to verify who approved a document, when they approved it, and which version they reviewed.

All review and approval activities should be conducted within a controlled system. An appropriate platform will capture every action in a secure, time-stamped audit trail, creating a single source of truth that definitively connects each electronic signature to a specific document version. This provides the verifiable evidence regulators require.

Failure to Trace Amendment Impacts

Failing to track the downstream impact of a protocol amendment is a critical pitfall. An amendment affects not only the protocol but also the Informed Consent Form (ICF), Investigator's Brochure (IB), Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP), and other trial documents.

If these connections are not formally tracked, sites may use an outdated ICF, or the statistics team may analyze data against incorrect endpoints. Such disconnects compromise the trial's logical integrity and can introduce risks to patient safety and data integrity.

To avoid this, a traceability matrix should be used to map the relationships between core documents. When an amendment is drafted, this map serves as a checklist, ensuring that every impacted document is identified, updated, and re-approved, thus maintaining study-wide consistency.

Building an Audit-Ready Documentation Strategy

Effective document traceability in the clinical trial lifecycle is not achieved through a single tool or checklist. It is an operational discipline, integrated into daily work through a framework of process, people, and technology.

This approach is not about creating administrative burdens but about shifting from a reactive mindset to a proactive one where quality is built-in. The goal is to create a documentation ecosystem where every critical record has a complete, logical, and verifiable history by default.

The Three Pillars of a Traceable System

A resilient strategy depends on three interconnected pillars. Weakness in one can destabilize the entire structure, creating compliance gaps.

- Process: This is the foundation. It begins with clear, enforceable standard operating procedures (SOPs) that define the entire document lifecycle. SOPs must specify how version control is managed, what metadata is required, and the workflows for review and approval, leaving no room for ambiguity.

- People: Effective processes and tools are of little value if the team does not understand how or why to use them. This pillar involves defining clear roles and responsibilities for authors, reviewers, and approvers. It also requires ongoing training to ensure everyone understands that adherence to these procedures is fundamental to patient safety and regulatory compliance.

- Technology: Appropriate technology provides the controls and automation needed to enforce processes. The focus is not on a specific vendor but on ensuring platforms provide essential features: immutable, time-stamped audit trails, automated versioning, and controlled access.

A sound traceability strategy is ultimately about demonstrating control. An auditor needs to see evidence of a deliberate, systematic approach to managing documentation. A strategy that integrates process, people, and technology provides this proof, showing that quality is part of the organizational culture.

When these three elements work in concert, the result is an interconnected system that ensures data integrity, protects patients, and maintains a state of inspection-readiness from the first protocol draft to the final clinical study report.

Frequently Asked Questions About Document Traceability

Understanding document traceability across the clinical trial lifecycle involves considering its practical application. Here are common questions from clinical operations, regulatory affairs, and medical writing professionals.

What Is The Difference Between Document Traceability and a TMF Checklist?

A TMF checklist is an inventory tool. It confirms that the final, approved protocol is present and filed correctly in the Trial Master File. It answers the question, "Is the document here?"

Document traceability, in contrast, provides the document's complete history. It shows not only that the protocol is present but also how it reached its final state. It allows one to see which draft was sent for medical review, identify the specific reviewer comment that led to a change in inclusion criteria, and verify the precise date and time of final electronic approval.

A checklist confirms the existence of the final artifact. Traceability provides the full, auditable narrative of its development.

How Does ICH E6 R3 Change Requirements For Document Traceability?

The upcoming ICH E6(R3) guideline promotes a more proactive, risk-based approach often referred to as Quality by Design (QbD). This shift elevates traceability from a record-keeping task to a critical component of a quality assurance strategy.

Under R3, it is not sufficient to merely have a compliant audit trail. Organizations must demonstrate that the trial's design and execution were structured to protect data integrity and patient safety from the outset. Traceability serves as the evidence, connecting the critical-to-quality (CtQ) factors identified during planning directly to the procedures defined in the protocol and other core documents.

Can We Achieve Full Traceability Using Email and Shared Drives?

Relying on email and shared drives for GxP-critical workflows presents a significant regulatory risk. While a history could theoretically be compiled through disciplined manual logging, these tools lack the inherent controls required for the clinical trial environment.

It is nearly impossible to definitively prove which version of a document is official, who approved it, or how key feedback was resolved when relying on email chains and folder histories. This results in disconnected records that are a concern for inspectors.

Purpose-built platforms provide immutable audit trails, structured review cycles, and controlled versioning as core functionalities. These systems are designed to create a defensible, verifiable history for every document, thereby meeting regulatory expectations by design.