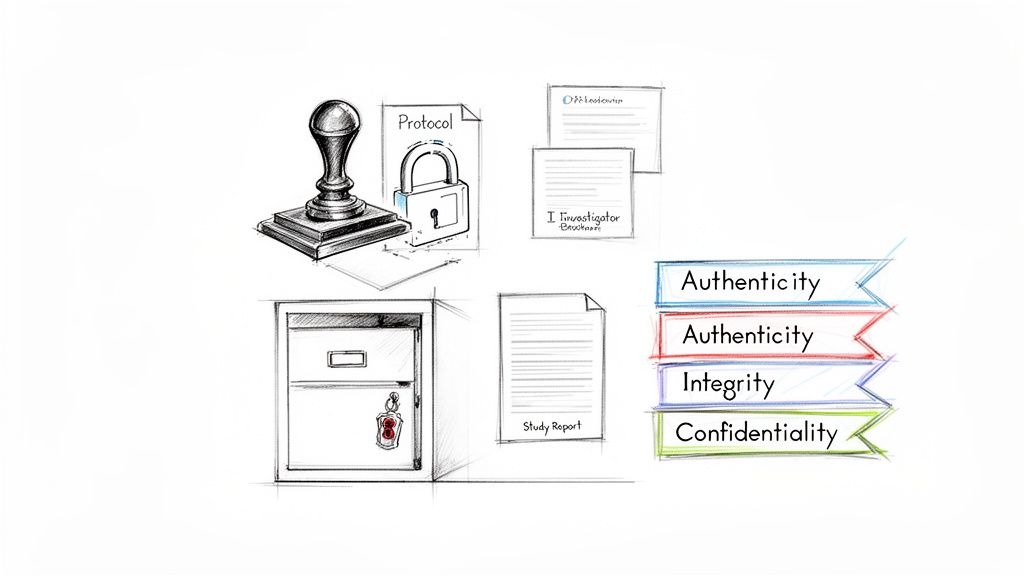

The FDA 21 CFR Part 11 regulation defines the criteria under which electronic records and electronic signatures are considered trustworthy, reliable, and equivalent to paper records. For clinical documentation, this requires implementing specific procedural and technical controls to ensure the authenticity, integrity, and, where appropriate, the confidentiality of electronic records. These controls affect how clinical trial documents are created, reviewed, modified, maintained, and archived.

Understanding The Foundations of 21 CFR Part 11

In the context of clinical development, 21 CFR Part 11 establishes the regulatory framework for the FDA's acceptance of electronic records and signatures in place of their paper counterparts. It is not a technical guideline but a core regulation that underpins the reliability of electronic data submitted to the agency.

The regulation's purpose is to protect the integrity of electronic data, which is essential for ensuring patient safety and enabling sound regulatory decision-making. Before the implementation of Part 11, the industry's transition from paper-based systems exposed vulnerabilities in data management, such as the potential for unrecorded alterations and challenges in record retrieval.

A Framework for Digital Integrity

Part 11 can be understood as a set of rules governing two primary areas: electronic records and electronic signatures.

- Electronic Records: The regulation mandates that electronic documents—such as protocols, Investigator’s Brochures, and Clinical Study Reports—are stored in a manner that prevents unauthorized modification and maintains a detailed, unalterable history of all changes.

- Electronic Signatures: It provides criteria to ensure that an electronic signature is the legally binding equivalent of a handwritten signature, uniquely attributable to a specific individual who performed a conscious, documented action.

Introduced in 1997, 21 CFR Part 11 was established to formalize the requirements for electronic systems used by pharmaceutical companies, biotechnology firms, and contract research organizations (CROs). The rule mandated controls to protect the integrity of records like electronic Case Report Forms (eCRFs) and electronic informed consent forms. You can read more about the history of Part 11 and its evolution.

Core Principles in Practice

To apply Part 11 effectively, it is necessary to focus on its foundational principles. These principles represent a systematic approach to maintaining verifiable data integrity throughout the entire document lifecycle.

The following table outlines the core tenets of the regulation and their practical impact on clinical trial documentation.

Core Tenets of 21 CFR Part 11 Explained

| Core Tenet | Regulatory Intent | Impact on Clinical Documents |

|---|---|---|

| Audit Trails | To reconstruct all events related to the creation, modification, or deletion of an electronic record. | Every change to a protocol, report, or any other electronic record must be logged with a timestamp, user ID, and the details of the change. |

| Access Controls | To ensure that only authorized individuals can access the system, perform specific functions, and sign records. | A system must limit who can author, review, approve, or view documents based on their defined role in the clinical trial. |

| Electronic Signatures | To create legally binding signatures that are uniquely linked to one individual and cannot be repudiated. | Signatures on a final Clinical Study Report or an approved protocol amendment must be as legally valid as a wet-ink signature, supported by identity verification. |

| Record Integrity | To ensure that electronic records cannot be altered in a way that obscures or deletes the original data. | Documents must be stored in a format that prevents tampering. If changes are made, both the original data and the changes must be preserved and traceable. |

Ultimately, these principles work toward a single objective: ensuring electronic records are dependable.

The ultimate goal of Part 11 is to ensure that electronic records are dependable and can be relied upon with the same confidence as paper records. This confidence is essential for every document that informs the safety and efficacy of an investigational product.

This necessitates both procedural and technical controls covering the entire document lifecycle. From the initial draft of a protocol to the final, locked Clinical Study Report (CSR), every action must be attributable, every modification traceable, and the final record a verifiable source of truth.

Breaking Down the Key Technical Controls for Compliance

To implement 21 CFR Part 11 within daily operations, specific technical controls are required. These are not optional features but the foundational elements of any system used to manage electronic clinical documents. These controls provide the digital framework that ensures every record is authentic, reliable, and complete from creation to archival.

The operational rationale for these controls is the generation of verifiable evidence. Every interaction with a clinical document—whether creation, modification, or approval—must be traceable and secure. This transforms document management from a system based on operational trust to one based on auditable proof, which is the standard expected by regulatory authorities.

Secure Audit Trails: The Unchangeable Story of a Document

A secure, computer-generated, time-stamped audit trail is a critical technical control. It serves as a permanent, uneditable history for every electronic record within a system. This log must automatically capture any action that creates, modifies, or deletes a document, creating a complete and unbroken record.

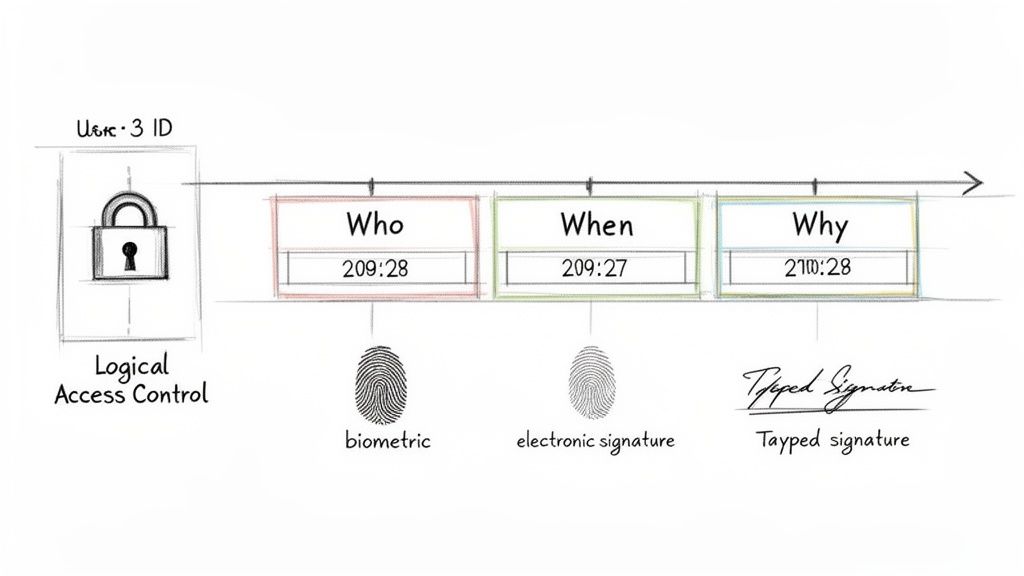

For example, when amending a study protocol, the audit trail for that document would record:

- Who made the change (the user's unique ID).

- When the action occurred (a precise date and time stamp).

- What was changed (capturing both old and new values).

- Why the change was made (often a required field for justification).

This level of detail is necessary to allow an inspector to reconstruct the document's history and verify that all modifications were authorized and intentional. Since Part 11 came into effect in 1997, it has fundamentally reshaped how clinical trial data is managed. Even with the FDA's 2003 guidance clarifying a risk-based approach, the need for trustworthy records, such as statistical analysis plans, remains. Before Part 11, audits often revealed that a significant percentage of data errors in clinical trials stemmed from manual processes in systems lacking these now-mandatory audit trails (sections 21 CFR 11.10(d)-(k)).

Logical Access Controls: Defining Who Can Do What

Logical access controls function as the gatekeepers of a system, ensuring that individuals can only perform actions for which they are explicitly authorized. This extends beyond simple login credentials to granular, role-based control over all system functions.

A properly configured system links a user's identity directly to their role and associated permissions. For example, a medical writer may have permission to author and edit a draft Clinical Study Report (CSR). A Quality Assurance team member might only have permission to view that same document and add comments. The final approver, such as a Chief Medical Officer, would be the only individual with the authority to apply a legally binding electronic signature.

The purpose of access control is to enforce a strict separation of duties and prevent unauthorized or accidental changes that could compromise a document's integrity. It ensures every interaction is appropriate for that user's specific role in the trial.

These controls must be robust. The system must be designed to prevent a reviewer from directly editing a document that is locked for their review, thereby preserving the integrity of the controlled draft. This is a non-negotiable feature for managing documents within an electronic trial master file system.

Electronic Signatures: Proving Identity and Intent

Part 11 specifies strict requirements for electronic signatures to ensure they carry the same legal weight as handwritten signatures. While the regulation accommodates different signature types, all must be uniquely linked to one individual and non-reusable.

A common method involves a two-component approach:

- Identification Code: A unique username that identifies the signer.

- Password: A confidential string of characters known only to the user.

When a document is signed, the system must capture more than the signature itself. It must record the signer's printed name, the exact date and time, and the "meaning" of the signature—such as "Approval," "Review," or "Authorship." This information becomes a permanent, non-modifiable part of the record, creating an accountable and legally binding link between the individual, their action, and their intent.

Mastering System Validation and Change Control

System validation is a frequently misunderstood aspect of 21 CFR Part 11. It is often treated as a one-time event performed upon system installation. However, this interpretation is incorrect.

Validation is an ongoing process, not a singular event. Section 11.10(a) states that any system used to handle electronic records must be validated to demonstrate that it is accurate, reliable, and consistently performs as expected. This involves creating documented evidence that a clinical documentation platform functions as intended. It is the distinction between asserting compliance and proving it.

It is also important to distinguish between system validation and the routine approval of a document. Validating the system certifies that the tool itself is fit for its GxP purpose. Approving a protocol within that system is a workflow that relies on that underlying validated state.

The Pillars of System Validation

A formal validation effort is a structured, meticulously documented project that produces a complete evidence package. This package is presented to auditors to demonstrate the trustworthiness of the electronic records.

A standard validation package includes several key components:

- Validation Plan: This document outlines the overall strategy, including what will be tested, who will conduct the testing, the testing methodology, and the acceptance criteria.

- User Requirements Specification (URS): The URS defines the essential business and regulatory needs the system must meet, such as non-editable audit trails, version control, and compliant electronic signatures.

- Installation Qualification (IQ): This documentation verifies that the software was installed correctly according to the vendor’s specifications and within the defined IT environment.

- Operational Qualification (OQ): OQ involves testing individual system features in a controlled manner to ensure they function as designed (e.g., confirming access controls prevent unauthorized actions).

- Performance Qualification (PQ) / User Acceptance Testing (UAT): This phase involves end-users, such as clinical operations and medical writing teams, executing test scripts that simulate their daily tasks to confirm the platform meets their operational needs.

- Validation Summary Report: This final document summarizes the entire validation effort, presents the test results, and includes a formal statement confirming the system is fit for its intended use.

The Critical Role of Change Control

Once a system is validated, it exists in a compliant state. Any subsequent change has the potential to alter this state. Change control is the formal process used to manage and document all modifications to a validated system.

Change control is the formal process that ensures the validated state of a system is maintained over its entire lifecycle. It prevents unmanaged changes from introducing risks that could compromise data integrity or regulatory compliance.

Change control applies not only to major software upgrades but also to vendor-supplied patches, server updates, system configuration adjustments, or changes to user permissions.

Every proposed change must undergo a formal review where the change is documented, its potential impact is assessed, and any required re-testing or re-validation is determined before implementation. A disciplined change control process is essential for maintaining a continuous state of inspection readiness. Further details on this topic can be found by exploring the fundamentals of change control in clinical trial documentation.

Applying Part 11 Principles to Daily Documentation Workflows

Understanding the technical requirements of 21 CFR Part 11 is distinct from applying them to real-world clinical documentation processes. The principles of authenticity, integrity, and confidentiality must be integrated into every step of a document's lifecycle. A compliant workflow ensures that a document is a verifiable, authoritative record from its initial draft to its final, signed version.

This is where the operational implications of 21 CFR Part 11 for clinical documentation become evident. The following example traces an Investigator's Brochure (IB) through a typical workflow within a controlled system.

Before a document's lifecycle begins, the system itself must be validated. This is a continuous process, not a one-time task.

This process—plan, test, and control—is the foundation of trustworthy documentation. System reliability begins with careful planning, is verified through rigorous testing, and is maintained through continuous control.

Structured Authoring and Controlled Templates

The lifecycle of the IB begins with a controlled template, not a blank document. This enforces a standardized structure, ensuring the document aligns with regulatory standards like ICH E6 from its inception. A Part 11-compliant system also ensures that only authorized individuals can initiate the authoring process, linking the act of creation to a specific, identifiable user.

This initial step is foundational. Using pre-defined templates promotes consistency, ensures critical sections are not omitted, and reduces the potential for human error. The first "save" action creates the initial entry in the document's permanent audit trail, time-stamped and linked to its author.

Collaborative Review with a Permanent Record

Once a draft is complete, it enters the review stage. Here, Part 11 controls extend beyond simple access permissions. Reviewers, such as the Medical Monitor or a Regulatory Affairs representative, are assigned specific roles. They can view the document and provide feedback, but they cannot directly alter the author's original text.

Every comment, question, and suggestion is captured and logged as a permanent, time-stamped part of the record, creating a fully transparent history of the entire review process. This provides an auditor with evidence that all feedback was systematically addressed.

This is a direct, practical application of the audit trail requirement. It replaces informal, off-record modifications with a formal process, ensuring the full history of the document’s evolution is preserved. It demonstrates not just what changed, but also the rationale why.

Robust Version Control and Audit Trails

As the author incorporates feedback and refines the document, the system increments the version number (e.g., from v0.1 to v0.2). A compliant system never overwrites a previous version. Instead, it archives the older version, creating a complete, auditable chain of custody. Authorized users can retrieve and compare any two versions, and the audit trail logs every modification, linking it to an individual, a timestamp, and often, a reason for the change.

This meticulous versioning is a non-negotiable requirement. If an inspector raises questions months or years later, the document's entire history can be reconstructed, showing precisely how it evolved from one iteration to the next.

For over 25 years since 21 CFR Part 11 was enacted on August 20, 1997, its principles have become the standard for validating electronic systems in clinical trials. The FDA’s 2003 guidance helped focus these efforts on the most critical records. Today, requirements from Subpart B—such as secure audit trails and unique electronic signatures—are standard expectations for documents like informed consent forms and investigator's brochures, ensuring they are as trustworthy as paper records. The FDA's guidance on the scope and application of Part 11 provides further insight into the agency's thinking.

Formal Electronic Signature for Final Approval

Finally, the IB is ready for approval. The system initiates a formal electronic signature workflow, routing the document to designated approvers. To apply their signature, each individual must re-authenticate their identity, typically by entering their unique username and password.

Before signing, the system clearly states the "meaning" of the signature, such as "I approve this document for use." This action binds their digital signature to that specific version of the IB, creating a legally binding record that cannot be repudiated. The signed document is then locked, becoming the official, authoritative version ready for distribution, with its integrity assured.

The table below illustrates how specific Part 11 controls map directly to different stages of a document’s lifecycle.

Part 11 Controls in The Document Lifecycle

| Document Stage | Applicable Part 11 Control | Operational Example |

|---|---|---|

| Drafting | §11.10(a) Access Controls | Only an authorized Medical Writer can create or edit a draft Investigator's Brochure within the system. |

| Review | §11.10(e) Audit Trails | A reviewer's comments are logged with their name and a timestamp, creating a permanent record of feedback. |

| Revision | §11.10(b) Version Control | When a draft is updated, it is saved as v0.2, and v0.1 is archived and remains accessible. The system logs who made the change. |

| Approval | §11.200 Electronic Signature | The Principal Investigator signs off on the final IB by entering their unique ID and password, which is linked to their name. |

| Storage & Retrieval | §11.10(c) System Security | The final, approved IB is stored in a secure, backed-up repository, retrievable only by users with specific permissions. |

This mapping demonstrates that compliance is not a single event but a continuous process embedded in every action taken within a validated system.

Maintaining Inspection Readiness with Compliant Documentation

The definitive test of a 21 CFR Part 11 compliance program occurs during a regulatory inspection. Compliance is demonstrated by the ability to prove, on demand, that electronic records are under complete control.

This requires a shift from a reactive state of document retrieval to one of proactive, continuous readiness. A Part 11-aligned system does not merely store files; it maintains them in a constant state of inspection readiness.

Demonstrating Compliance Under Scrutiny

When an inspector arrives, their objective is to verify the trustworthiness of electronic records and signatures. They will test systems with specific, targeted requests designed to assess the integrity of clinical documentation.

For instance, an inspector might request a specific protocol amendment from six months prior and expect immediate retrieval. They will then likely request the full, human-readable audit trail for that document to reconstruct its entire history—from creation through every modification to final approval.

The core of an inspection is not just about showing the final document, but about proving the integrity of the entire process that produced it. An intelligible audit trail and verifiable electronic signatures provide the objective evidence that the process was controlled and compliant.

This directly tests a system's capabilities and the team's ability to operate it correctly under pressure.

What Auditors Look for in Clinical Documentation Systems

Auditors require tangible proof that Part 11 controls are functioning as intended by observing the system in action.

Key areas of examination typically include:

- Version and Document Retrieval: The speed and accuracy with which a specific historical version of a document, such as an archived informed consent form, can be located and displayed.

- Audit Trail Integrity: The ability to produce a clear, time-stamped audit trail for a document, detailing who made changes, when they were made, and the old versus new values.

- Electronic Signature Verification: For any signed document, the ability to demonstrate how the signature is linked to that record, including the printed name, the exact date and time, and the meaning of the signature (e.g., "Approval").

- Access Control Logic: The ability to explain and demonstrate how the system prevents unauthorized actions, such as an unqualified user approving a Clinical Study Report.

Supporting Documentation: The Foundation of Trust

In addition to live system demonstrations, auditors will review the supporting documentation that substantiates an organization's commitment to compliance. This is where procedural controls and system validation documentation are critical. For more context on how this integrates into the broader regulatory framework, refer to this guide on Trial Master File completeness and inspection readiness.

Be prepared for requests to review these documents:

- System Validation Package: The complete collection of records proving the system was validated for its intended use.

- Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): Official, written instructions detailing how the team manages electronic records and signatures.

- Personnel Training Records: Documented evidence that all system users have been trained on both the software and the relevant SOPs.

Ultimately, inspection readiness is the outcome of a well-designed system, robust procedures, and a well-trained team. It is the practical, daily result of embedding the principles of 21 CFR Part 11 into clinical documentation management.

Looking Beyond the Rules: The Real Value of Part 11 in Clinical Development

Viewing 21 CFR Part 11 solely as a regulatory requirement is a missed opportunity. It is more accurately a strategic framework for protecting the scientific and operational integrity of a clinical program. The regulation is fundamentally about safeguarding an organization's most critical asset: its data.

Adhering to the principles of Part 11 yields tangible benefits, most notably a significant reduction in the risk of data integrity findings during an inspection. Such findings can lead to project delays, extensive queries, or, in the most severe cases, the rejection of a regulatory submission.

An Investment in Credibility and Speed

Ensuring that every clinical document is authentic, trustworthy, and has a complete, unchangeable history builds a foundation of credibility with regulatory agencies. This confidence can contribute to a more efficient submission review process.

Think of adopting Part 11-compliant systems not as an expense, but as a core investment in the quality and defensibility of your clinical research. It is an essential pillar for succeeding in an increasingly digital-first regulatory environment.

This proactive approach keeps critical documents—from the protocol and investigator’s brochure to the final clinical study report—in a continuous state of inspection readiness. This operational discipline is a significant advantage for sponsors, biotechs, and CROs.

Building a Foundation for Success

The implications of FDA 21 CFR Part 11 for clinical documentation extend beyond regulatory compliance. Embracing the regulation's intent fosters a culture of quality, precision, and accountability that positively impacts every stage of the document lifecycle.

- Increased Efficiency: Less time is spent on manual quality checks and correcting avoidable errors.

- Improved Collaboration: A secure, controlled system makes team reviews more efficient and reliable.

- Enhanced Data Quality: The system enforces consistency and completeness from the point of document creation.

By focusing on the regulation’s intent rather than treating it as a checklist, organizations can improve operational efficiency while ensuring their clinical data withstands the highest level of regulatory scrutiny.

Your Questions About 21 CFR Part 11, Answered

Applying the principles of 21 CFR Part 11 to daily clinical trial documentation workflows often raises practical questions. The following section addresses some of the most common inquiries from clinical operations and regulatory professionals.

Compliant Systems Versus Compliant Processes

A common point of confusion is the distinction between a compliant system and a compliant process. Both are required to meet regulatory expectations.

A Part 11 compliant system pertains to the technology itself. It must have the built-in technical controls required by the regulation, such as secure, non-editable audit trails, granular access controls, and a validated electronic signature function.

A Part 11 compliant process pertains to how people use that system. This includes the SOPs, training records, and documented workflows that define how user roles are managed, password policies are enforced, and system changes are controlled.

An organization can procure a system with all the necessary technical features, but without clear, enforced procedures for its use, it will not be compliant. True compliance exists at the intersection of a validated system and the well-defined, consistently followed processes that govern its use.

Which Clinical Trial Documents Actually Need to Be Compliant?

The requirements of Part 11 do not apply to every electronic file related to a clinical trial. The FDA's 2003 guidance on the regulation's scope and application encourages a risk-based approach.

The rule of thumb is this: Part 11 controls apply to electronic records that are required to be created, modified, maintained, or submitted under other FDA regulations (known as “predicate rules”). This helps focus compliance efforts on high-impact GxP documents.

In practice, this means final, approved versions of the protocol, Investigator's Brochure, informed consent forms, Statistical Analysis Plans (SAPs), and the final Clinical Study Report are clearly within scope. These are the records that inspectors will scrutinize.

Conversely, internal team brainstorming notes, early informal drafts, or a project management tracker for internal deadlines would likely not require the full suite of Part 11 controls. However, it remains good practice to manage these documents in a controlled manner.

Where Do I Start with Assessing Part 11 Compliance?

For organizations initiating a compliance assessment or evaluating their current state, the first step is a comprehensive inventory and risk assessment of all relevant systems.

A practical approach includes these steps:

- Map your systems. Identify every system that creates, modifies, or stores GxP-relevant electronic records. This includes the eTMF, EDC systems, data analysis software, and any other related platforms.

- Conduct a gap analysis. Evaluate each system against the technical requirements of Part 11. Document all identified gaps, such as an inadequate audit trail or a lack of role-based access controls.

- Review your procedures. Examine all existing SOPs and procedural documents to determine if they adequately cover the compliant use of these systems.

- Develop an action plan. Based on the identified gaps, create a remediation plan. Prioritize the highest-risk issues first, which typically involves focusing on systems that manage records critical for patient safety and regulatory submissions.

This structured assessment provides a clear, actionable roadmap for achieving and maintaining compliance, establishing the foundation for being inspection-ready at all times.