Medical writing for clinical trials is a specialized discipline focused on preparing clear, structured, and compliant documentation required by regulatory bodies such as the FDA and EMA for the approval of new therapies. Its primary function is to translate complex scientific and clinical data into a cohesive set of documents that accurately represent a trial's conduct and outcomes.

Effective medical writing ensures that even the most complex research is presented in a format that is understandable, verifiable, and suitable for regulatory review, thereby facilitating the progression of investigational products through the development lifecycle.

The Role of the Medical Writer in Clinical Development

The medical writer serves as a central figure in the creation and management of clinical trial documentation. This role has evolved from a support function to a strategic component of clinical development, responsible for authoring and maintaining the official record of a study.

The core responsibility of a medical writer is to ensure that all documentation is precise, internally consistent, and compliant with applicable regulations and guidelines. This involves authoring an interconnected suite of documents that define the study's operational framework and report its findings, ensuring they are prepared for potential regulatory inspection.

From Study Design to Final Report

Clinical trial documentation is a dynamic and evolving record that must be meticulously managed throughout the study lifecycle. The medical writer's work forms the official narrative that health authorities review, where accuracy and clarity are paramount.

Key documents produced during a clinical trial include:

- Clinical Trial Protocols (CTPs): This document serves as the operational blueprint, detailing the study's objectives, design, methodology, and procedures.

- Investigator's Brochures (IBs): A comprehensive summary of all relevant nonclinical and clinical data on the investigational product.

- Informed Consent Forms (ICFs): A critical document explaining the study to potential participants in clear, non-technical language to support their decision-making process.

- Clinical Study Reports (CSRs): The final, comprehensive report that presents the trial's results and statistical analyses. The structure of a CSR is detailed in our clinical study report template.

This function requires a combination of scientific expertise and a thorough understanding of regulatory frameworks. Medical writers must integrate complex data into a coherent narrative that adheres to the standards set by bodies like the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH).

Medical writing serves as the essential link between raw clinical research data and regulatory comprehension. Its objective is to present a clear, unbiased, and verifiable account of a trial's conduct and results, where every statement is supported by evidence.

The growth in global clinical research has increased the demand for skilled medical writers. As of May 2023, there were 452,604 studies registered on ClinicalTrials.gov. The market for medical writing is projected to constitute a 35.6% share of the clinical trial services industry by 2025, as reported by researchandmarkets.com.

Core Documents in Clinical Trial Operations

Medical writing in a clinical trial involves assembling a comprehensive file of evidence where each component is interconnected and consistent. Each document serves a specific operational and regulatory purpose, and together they form a single, coherent record for submission to regulatory authorities.

The process is anchored by two fundamental elements: the structured documentation that defines the study and the clinical data generated from its execution.

Successful clinical development depends not only on data collection but also on creating a robust, auditable narrative that substantiates every data point, all originating from the trial's core strategic plan.

The Clinical Trial Protocol (CTP): The Study's Blueprint

The Clinical Trial Protocol (CTP) is the foundational document of any study. It is an operational manual that specifies the trial's objectives, design, methodology, statistical considerations, and overall organization.

The CTP's primary role is to ensure that all parties involved—from investigators at various sites to clinical operations staff—adhere to a standardized plan. This consistency is essential for maintaining data integrity.

A well-structured protocol does more than outline procedures; it also anticipates operational challenges. Medical writers are responsible for translating scientific objectives into a clear and unambiguous operational plan that aligns with ICH E6 (Good Clinical Practice) guidelines. Any subsequent modification to the study, such as changes to inclusion criteria or dosage, requires a formal protocol amendment, creating a transparent and auditable record for regulators and ethics committees.

The Investigator’s Brochure (IB): The Scientific Rationale

While the protocol explains how the study will be conducted, the Investigator’s Brochure (IB) explains why. This document provides a comprehensive compilation of the existing clinical and non-clinical data on the investigational product, intended primarily for clinical investigators and their staff.

Its purpose is to provide investigators with the necessary scientific context to understand the trial's rationale and to manage patient safety effectively. The IB covers the product's pharmacology, toxicology, pharmacokinetics, and any available data from prior human studies.

Medical writers must ensure the IB is maintained and updated at least annually, or more frequently if significant new safety information becomes available. This is a fundamental requirement for the ethical conduct of clinical trials.

Informed Consent Forms (ICFs): The Participant Agreement

The Informed Consent Form (ICF) is the primary communication tool between the trial sponsor and the participant. This document explains all aspects of the study, including its purpose, procedures, potential risks and benefits, and the participant's right to withdraw at any time.

The medical writer's task is to draft a document that meets strict regulatory requirements (such as 21 CFR Part 50 in the U.S.) while using clear, simple language that is accessible to a layperson. The goal is not merely to obtain a signature but to facilitate a genuinely informed decision-making process.

The Clinical Study Report (CSR): The Final Account

The Clinical Study Report (CSR) is the definitive, comprehensive account of the trial's conduct and results. It is one of the most complex and critical documents submitted to regulatory authorities, integrating all study data, analyses, and conclusions into a final narrative.

The structure of the CSR is rigorously defined by ICH E3. It provides a complete clinical and statistical description of the study, integrating tables, figures, and data listings into a cohesive report that supports conclusions regarding the product's safety and efficacy.

A CSR must present a complete and unbiased account of the trial, including positive, negative, and inconclusive findings. Its standardized structure is designed to allow regulatory reviewers to independently assess the evidence and form their own conclusions.

Preparing a CSR is a significant undertaking. All claims must be consistent with the protocol and substantiated by data. Minor discrepancies can lead to significant queries during regulatory review, potentially causing delays or jeopardizing the submission. The importance of these documents is reflected in the 35.6% global market share held by the clinical writing services market.

This table summarizes these key documents and their corresponding guidelines.

Key Clinical Trial Documents and Their Regulatory Purpose

| Document | Primary Purpose | Governing ICH Guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trial Protocol (CTP) | To provide a detailed blueprint of the study's objectives, design, methodology, and organization. | ICH E6 (R2) – Good Clinical Practice |

| Investigator’s Brochure (IB) | To compile all relevant clinical and non-clinical data on the investigational product for investigators. | ICH E6 (R2) – Good Clinical Practice |

| Informed Consent Form (ICF) | To explain the trial to potential participants in clear language, ensuring their decision is voluntary and informed. | ICH E6 (R2) & local regulations |

| Clinical Study Report (CSR) | To present a comprehensive and integrated report of the trial’s methods and results for regulatory submission. | ICH E3 – Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports |

Each document is a critical component of the regulatory submission package. A more extensive list of regulatory documents in clinical trials can be found in our related guide.

Navigating the Global Regulatory Landscape

Medical writing for clinical trials requires adherence to a complex framework of international and regional standards. These regulations are in place to ensure data integrity, ethical conduct, and patient protection.

Understanding this regulatory context is essential for medical writers to function as strategic partners who develop documentation designed for regulatory acceptance from the initial draft.

ICH: A Harmonizing Force in Global Trials

The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) is a key organization in this field. ICH brings together regulatory authorities from Europe, Japan, and the United States with pharmaceutical industry experts to develop unified guidelines. Its purpose is to promote the efficient development and registration of safe and effective medicines across jurisdictions.

While ICH guidelines are not legally binding statutes, they are recognized as the global standard. Major health authorities expect adherence to these guidelines, making them essential for sponsors seeking to market products in multiple regions.

The mission of ICH is to achieve greater harmonization worldwide to ensure that safe, effective, and high-quality medicines are developed and registered in the most resource-efficient manner. This is accomplished by developing and agreeing upon harmonized technical guidelines.

For medical writers, two guidelines are particularly important:

- ICH E6 (Good Clinical Practice): This guideline sets the standard for the design, conduct, performance, monitoring, auditing, recording, analysis, and reporting of clinical trials, ensuring both patient safety and data credibility.

- ICH E3 (Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports): This document provides specific guidance on the format and content of a Clinical Study Report (CSR), ensuring a standardized presentation of trial findings for regulatory review.

Regional Regulatory Bodies: FDA and EMA

While ICH provides a global framework, regional authorities like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) establish specific requirements for their respective jurisdictions.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

In the United States, the FDA's regulations are codified in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). Title 21 is the primary source for these rules. For example, 21 CFR Part 50 outlines the requirements for informed consent. The FDA also issues guidance documents that provide its current thinking on various topics.

European Medicines Agency (EMA)

The EMA is responsible for the scientific evaluation of medicines for the European Union. While heavily reliant on ICH standards, the EMA also has its own regional requirements. The EU Clinical Trials Regulation (CTR 536/2014) is a notable example, which introduced a centralized submission process through the Clinical Trials Information System (CTIS), altering documentation management for studies conducted in the EU.

An experienced medical writer must navigate the nuances between these regulatory frameworks. A document prepared for an FDA submission may require adjustments to meet EMA requirements. This regulatory awareness is crucial for preventing delays and ensuring a smooth submission process.

Best Practices for Document Quality and Consistency

Beyond regulatory compliance, maintaining high standards of quality and consistency across all trial documentation is essential for preparing an audit-ready submission. The entire set of clinical trial documents—including the protocol, CSR, and IB—should function as a single, interconnected narrative. Discrepancies between documents can raise significant questions during regulatory review.

Achieving this consistency relies on robust internal processes that make clarity and accuracy standard practice.

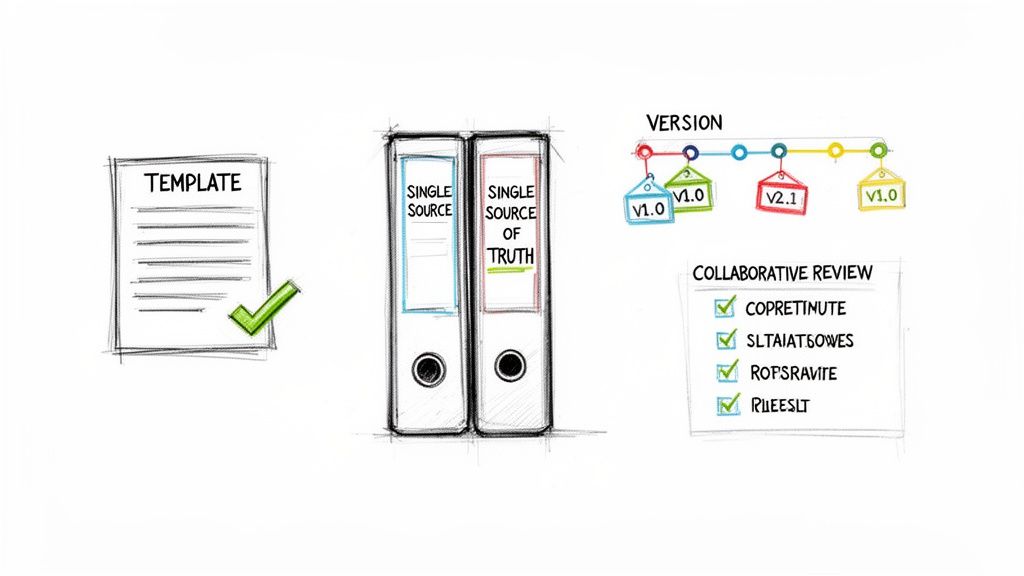

Establishing a Single Source of Truth

A core principle for ensuring consistency is the establishment of a single source of truth. This means that critical information, such as the primary study objective or the definition of a key endpoint, is defined in one authoritative location and referenced throughout all other documents. Inconsistencies often arise when different teams use siloed or outdated sources of information.

This can be achieved by creating controlled, centralized resources.

- Controlled Vocabularies: A master list of approved abbreviations, definitions, and terminology ensures that terms like "adverse event of special interest" are used consistently across the protocol, investigator's brochure, and CSR.

- Centralized Templates: Using pre-approved, standardized templates for major documents enforces a consistent structure and ensures all required sections from ICH guidelines are included.

This operational best practice significantly reduces the risk of contradictory information within a submission package.

Implementing Meticulous Version Control

Clinical trial documents are subject to frequent updates as new data becomes available or protocols are amended. Without a systematic version control process, teams risk working from outdated drafts, which can lead to protocol deviations and data integrity issues.

Effective version control is a formal, auditable process that documents the details of every change, including what was changed, why, and when. This provides regulators with a transparent document history.

A robust version control process includes several key components:

- Clear Naming Conventions: A standardized file naming system (e.g., Protocol_ABC-123_v3.0_FINAL) should be uniformly adopted.

- Change Logs: Each new version must be accompanied by a summary of changes from the previous version, which is particularly critical for protocol amendments.

- Controlled Access: A document management system should be used to ensure that team members only have access to the latest approved version of a document.

Executing Structured Review Cycles

The review process is a critical quality control step in medical writing for clinical trials. An unstructured review can introduce more errors than it resolves. A structured, cross-functional review process brings together experts from various disciplines to validate the document from multiple perspectives.

A well-defined review cycle assigns clear responsibilities:

- Clinical Operations: Assesses the operational feasibility of procedures described in the protocol at clinical sites.

- Biostatistics: Confirms the soundness of the statistical analysis plan and the accurate presentation of results in the CSR.

- Medical Monitors: Ensures the clinical accuracy and appropriate representation of all safety information.

- Regulatory Affairs: Verifies that the document complies with all relevant regional and international guidelines.

By integrating these perspectives in a structured manner, medical writers can produce documents that are scientifically, operationally, and regulatorily sound, moving beyond simple compliance to create audit-ready documentation.

The Role of Technology in Clinical Trial Documentation

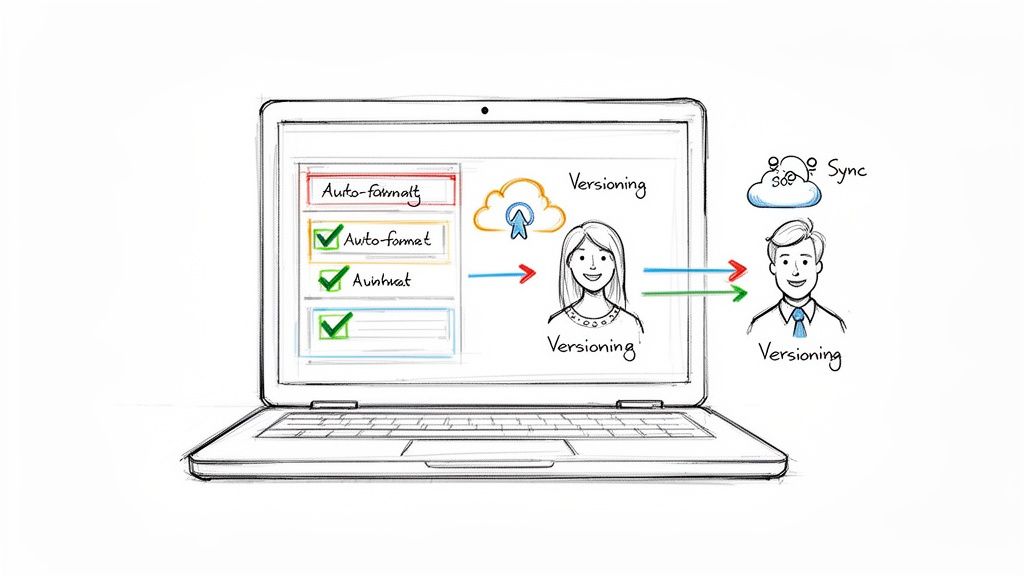

The volume of modern clinical trials has grown significantly. The number of registered trials increased from 24,822 in 2005 to 453,803 in 2023, according to data from market.us. This growth has created a corresponding increase in the documentation burden. Managing this volume with traditional methods can lead to errors and inefficiencies.

Specialized clinical documentation platforms can help manage this complexity. These systems do not replace medical writers but rather augment their work by automating repetitive tasks that are susceptible to human error. This allows writers to focus on the scientific integrity and clarity of the narrative.

From Manual Word Processing to Structured Authoring

Using standard word processors for large-scale clinical trials often results in inconsistent formatting, unclear version control, and conflicting terminology. Structured authoring platforms address these issues by incorporating regulatory requirements directly into document templates.

Instead of a blank document, a user begins with a Clinical Study Report template that is pre-configured to align with the ICH E3 structure. Each section is a defined component, guiding the writer to adhere to the required format. The process shifts from manual checklist verification to a system with built-in compliance.

Technology can integrate compliance into the document creation process itself. By embedding rules and structures directly into the workflow, it helps reduce the risk of human error and ensures consistency across trial documentation.

This structured approach also supports the establishment of a single source of truth. When a key piece of information is updated, the platform can propagate that change across all related documents, maintaining consistency without manual intervention.

Streamlining Collaboration and Review Cycles

Coordinating reviews among multiple stakeholders can be a complex logistical challenge, often involving numerous email chains and document versions. This can lead to confusion and difficulty in consolidating feedback.

Modern platforms provide a centralized environment for collaboration and review, designed for the specific needs of clinical documentation.

Key functionalities often include:

- Controlled Access: Ensures that reviewers are working with the most current and correct version of a document.

- Threaded Comments: Facilitates clear and organized discussions within the document, linked to specific text.

- Audit Trails: Automatically logs all comments, changes, and approvals, creating a transparent and traceable history suitable for the Trial Master File. The importance of audit-readiness is further detailed in our article on electronic trial master file software.

These tools transform the review process into a structured, efficient, and compliant operation, enabling teams to maintain the high standards required in today's clinical trial environment.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common questions that arise during the course of clinical development and medical writing activities.

What Is the Difference Between a Medical Writer and a Regulatory Writer?

While the terms are often used interchangeably, there is a functional distinction.

"Medical writer" is a broad term that can encompass individuals writing for medical journals, creating educational materials, or developing promotional content. These writers communicate scientific information to various audiences for different purposes.

A "regulatory writer" is a specialist whose work is focused on creating documents intended for submission to health authorities like the FDA or EMA. The practice of medical writing for clinical trials primarily falls under the scope of regulatory writing.

The key distinction lies in the audience and purpose. A regulatory document, such as a protocol or a Clinical Study Report (CSR), is not intended to be persuasive in a promotional sense. Its function is to present data and procedures with sufficient clarity and objectivity to allow a regulator to independently evaluate a product's safety and efficacy. This requires strict adherence to guidelines like ICH E6 and E3.

How Is Version Control Managed for Core Clinical Trial Documents?

Effective version control is a critical compliance function. It is a formal, systematic process that must be auditable.

A robust version control system, whether manual or platform-based, includes several key elements:

- Unique Identifiers: Each document is assigned a clear version number (e.g., Protocol v1.0, v2.0) and an effective date.

- Formal Amendments: Changes that could affect study conduct, patient safety, or data integrity necessitate a formal protocol amendment, resulting in a new, officially approved version of the document.

- Change Logs: Each new version should be accompanied by a summary of changes from the previous one, providing a transparent document history for auditors.

- Archiving: The Trial Master File (TMF/eTMF) must contain a complete record of all document versions, including drafts, review comments, and every final, approved iteration.

Modern platforms such as Skaldi can automate versioning, create a complete audit trail, and ensure that all team members are working from the most current document, which helps prevent protocol deviations.

What Are the Most Common Challenges in Preparing a CSR?

The Clinical Study Report (CSR) is a capstone document in clinical trial reporting. Its preparation involves several common challenges.

A Clinical Study Report serves as the ultimate test of a trial's narrative consistency. Any discrepancy between the CSR and its source documents, such as the protocol or statistical analysis plan, can be a significant red flag for regulatory reviewers.

Key hurdles in CSR preparation include:

- Maintaining Consistency: The narrative in the CSR must align perfectly with the protocol, its amendments, and the statistical analysis plan (SAP). All objectives, endpoints, and analyses presented in the report must be traceable to these foundational documents.

- Managing Data Volume: CSRs are extensive documents, often accompanied by thousands of pages of appendices containing tables, figures, and listings (TFLs). Organizing this volume of information and integrating it into the main report is a significant logistical task.

- Ensuring Objectivity: The purpose of the CSR is to present results—whether positive, negative, or inconclusive—without interpretation or promotional language. In accordance with ICH E3 guidelines, the writer must act as a neutral narrator, presenting the facts as they were observed.

- Coordinating Cross-Functional Review: The development of a CSR requires input and approval from clinicians, biostatisticians, regulatory affairs specialists, and other stakeholders. Managing this complex review process within tight timelines is a demanding project management exercise.

Addressing these challenges successfully requires well-defined processes, clear communication, and appropriate tools established well before the drafting process begins.