A clinical trial protocol is the detailed, formal plan for a research study. It is the single source of truth that defines the study's objectives, design, methodology, statistical considerations, and organizational structure. Its purpose is to ensure the safety of trial participants and the integrity of the data collected.

The Protocol's Role in Clinical Operations and Documentation

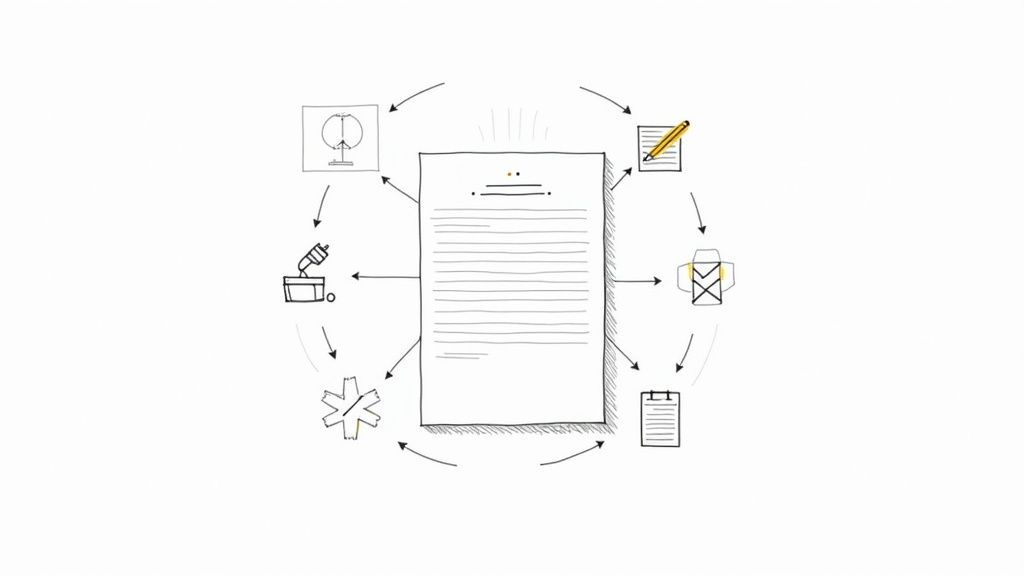

A well-structured protocol serves as the operational and scientific foundation for a clinical trial. It provides a standardized set of instructions for all stakeholders, including investigators, site staff, monitors, and auditors, to ensure consistent execution across all participating sites.

For Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), Independent Ethics Committees (IECs), and regulatory authorities such as the FDA and EMA, the protocol is a primary document for review. It allows them to assess the scientific validity, ethical framework, and feasibility of the proposed study.

The protocol's content directly informs the development of other critical trial documents. The procedures and risk assessments outlined within it are translated into the Informed Consent Form (ICF), ensuring participants receive a comprehensive understanding of their involvement. It also provides the scientific basis for the Investigator’s Brochure (IB) and the detailed specifications in the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP).

The Regulatory Context for Protocol Development

Protocol development does not occur in a vacuum. Its structure and content are guided by globally recognized standards, most notably the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guideline, specifically ICH E6(R2).

This guideline provides a unified standard for the European Union, Japan, and the United States to facilitate the mutual acceptance of clinical data by the regulatory authorities in those jurisdictions. Its purpose is to ensure that clinical trials are conducted ethically and that the data generated is credible and accurate, while protecting the rights, safety, and well-being of human subjects.

A key principle of ICH E6 is the integration of quality management into trial design and execution. This involves a risk-based approach, focusing on identifying, evaluating, and mitigating risks that could affect participant safety or data integrity.

The core principles of ICH E6(R2) directly influence protocol structure and content:

- Clear Objectives: The protocol must explicitly state the study’s objectives and define the primary and secondary endpoints.

- Sound Scientific Design: The trial design must be robust, methodologically sound, and scientifically justified to answer the research question.

- Participant Safety: The protocol must detail comprehensive plans for monitoring, managing, and reporting adverse events and other safety information.

- Data Integrity: The protocol must specify the methods for data collection, handling, and analysis to ensure data quality, reliability, and traceability.

A protocol developed in alignment with these principles is designed to be compliant and executable. It provides a clear, unified plan for all stakeholders, from the sponsor to the principal investigator, minimizing ambiguity and supporting operational success.

Core Components of an Executable Clinical Trial Protocol

Effective protocol writing requires adherence to regulatory guidelines and a focus on operational clarity. A protocol must be both compliant for regulatory submission and practical for implementation by clinical site staff.

The SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) guidelines offer a framework for ensuring a protocol contains the minimum set of items necessary for comprehensive reporting. While not a regulatory requirement, following SPIRIT can enhance the completeness and transparency of the protocol, potentially facilitating ethics committee and regulatory review.

Defining Study Objectives and Endpoints

The protocol synopsis provides a high-level summary of the study for reviewers, including IRB members and potential investigators. It should concisely present the trial's title, rationale, objectives, and overall design, enabling a reader to understand the study's scope and purpose quickly.

The definition of study endpoints is a critical section where precision is paramount.

- Primary Endpoints: The primary endpoint is the main outcome variable used to answer the primary research question. It is the basis for the sample size calculation and the key determinant of the trial's success. For example, a primary endpoint in a hypertension trial could be: "Mean change from baseline in systolic blood pressure at Week 12."

- Secondary Endpoints: Secondary endpoints are additional outcomes that support the primary endpoint or evaluate other effects of the intervention. A corresponding secondary endpoint might be: "Percentage of patients achieving blood pressure control (<130/80 mmHg) at Week 12."

Ambiguous endpoint definitions can lead to inconsistent data collection and inconclusive results. Using a structured template can help ensure all necessary sections are properly detailed.

Outlining Trial Design and Methodology

This section forms the operational core of the protocol. It must explicitly state the trial design (e.g., parallel-group, crossover, adaptive) and provide a clear justification for its selection based on the research objectives.

Complex methodologies such as randomization and blinding must be described in detail. The protocol should specify the randomization method (e.g., stratified block randomization via an Interactive Web Response System), the allocation ratio, and the personnel responsible for generating the randomization sequence. For blinding, the protocol must identify all blinded parties (e.g., participants, investigators, data analysts) and describe the mechanisms used to maintain the blind.

The study population criteria must be defined with precision. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are designed to create a homogenous population suitable for testing the study hypothesis, while also considering generalizability to the target patient population.

Overly restrictive exclusion criteria can present significant operational challenges, leading to recruitment difficulties. For instance, excluding patients with well-controlled comorbidities might improve internal validity but could make enrollment unfeasible. A balance must be struck between scientific rigor and operational reality.

Finally, the treatment regimen section must be unambiguous. It should detail the investigational product, dosage, administration route, and duration of treatment. The description of any placebo or comparator must be equally thorough to ensure blinding is maintained.

Adherence to Global Standards

For trials intended for multinational regulatory submissions, adherence to ICH E6 is a requirement. This guideline establishes a common framework that regulatory authorities in the US, Europe, and Japan recognize, facilitating a more streamlined review process.

Standardization efforts continue to evolve. The anticipated SPIRIT 2025 statement is expected to expand the checklist to 34 minimum items and recommend diagrams for schedules of events, aiming to further enhance the completeness and clarity of protocols from planning through to final reporting.

The table below summarizes the essential sections of an ICH E6-compliant protocol.

Key Sections of an ICH E6 Compliant Protocol

| Section Title | Primary Purpose | Key Content Elements |

|---|---|---|

| General Information | To provide administrative and summary details of the trial. | Protocol title, sponsor information, investigator details, synopsis. |

| Background & Rationale | To justify the trial based on existing scientific knowledge. | Description of the investigational product, summary of nonclinical and clinical findings, risk/benefit analysis. |

| Trial Objectives & Endpoints | To clearly state the scientific questions the trial aims to answer. | Primary and secondary objectives, specific endpoint definitions. |

| Trial Design & Methodology | To describe the scientific and operational plan for conducting the study. | Type of trial, description of treatments, randomization and blinding methods, study population criteria. |

| Safety & Efficacy Assessments | To detail how participant safety and study outcomes will be monitored. | Schedule of assessments, methods for recording adverse events, criteria for treatment discontinuation. |

| Statistical Methods | To pre-specify the plan for data analysis and interpretation. | Sample size calculation, statistical models, handling of missing data, interim analysis plans. |

This structure provides a robust foundation for developing a compliant and operationally sound clinical trial protocol.

Integrating Stakeholder Input and Feasibility Assessment

Protocol development is a collaborative process. A protocol drafted by a small, isolated team without input from operational stakeholders is at high risk of failure. A comprehensive feasibility and stakeholder review process conducted before the first draft is finalized is essential to mitigate the risk of costly amendments and operational issues.

This preliminary work helps ensure the final protocol is scientifically robust, operationally viable, and ethically sound.

Assembling a Cross-Functional Protocol Team

The initial step is to establish a cross-functional team with expertise spanning all relevant disciplines of the trial. Each member provides a unique perspective, helping to identify potential issues early in the process.

A core protocol development team typically includes:

- Clinicians and Medical Monitors: Responsible for the scientific and ethical integrity of the design, ensuring clinical relevance, appropriate endpoints, and robust patient safety measures.

- Biostatisticians: Define the statistical methodology, including sample size calculations and the analysis plan, to ensure the study is adequately powered to produce valid results.

- Regulatory Affairs Specialists: Provide guidance on ICH, FDA, EMA, and other applicable regulations to ensure the protocol meets health authority expectations.

- Clinical Operations Personnel: Offer insights into the practicalities of trial execution at the site level, assessing the feasibility of visit schedules, procedures, and data collection requirements.

Early involvement from these experts fosters shared ownership and improves the overall quality and executability of the protocol.

Conducting a Robust Feasibility Assessment

A protocol that is theoretically sound but operationally impractical is of little value. A thorough feasibility assessment is a required step to evaluate the protocol design against real-world constraints before finalization.

This assessment should go beyond site surveys to analyze how proposed inclusion/exclusion criteria align with actual patient populations. Overly stringent criteria, while intended to create a homogenous dataset, can severely impede enrollment, causing significant delays and budget overruns.

A common pitfall is developing a protocol without external input. Feedback from Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs) and patient advocacy groups can reveal operational challenges, such as a burdensome visit schedule or invasive procedures, that might otherwise be overlooked and could negatively impact recruitment and retention.

Incorporating a patient-centric approach by considering the participant's perspective and the potential burden of the trial can lead to design modifications that improve the overall trial experience and support enrollment goals.

Utilizing Technology for Feasibility Analysis

Technology, particularly artificial intelligence (AI), provides powerful tools for enhancing feasibility assessments. The market for AI-powered clinical trial feasibility tools has seen significant growth, from $0.65 billion to $0.83 billion in one year, reflecting a 27.5% growth rate. More details on this trend are available in the AI market growth on NatLawReview.com.

These tools can analyze large datasets, such as electronic health records and historical trial data, to model recruitment scenarios. They can help identify potential recruitment sites, forecast enrollment timelines, and flag protocol criteria likely to create bottlenecks.

This data-driven approach allows for proactive protocol refinement, optimizing the design for successful execution before site initiation. The combination of diverse human expertise and advanced technology is fundamental to creating a clear, compliant, and executable protocol.

A Disciplined Drafting and Review Workflow

The process of advancing a protocol from concept to a final, submission-ready document relies on a structured and iterative workflow. This cycle of drafting, stakeholder review, and refinement is essential for producing a protocol that is scientifically sound, operationally feasible, and compliant with regulatory standards.

The initial draft serves as the foundational document, translating strategic decisions from the planning phase into a structured format. This version provides a concrete basis for stakeholder review and feedback.

The Importance of Precise Scientific Writing

Ambiguity in a protocol can lead to inconsistent interpretations across clinical sites, potentially compromising data integrity and patient safety. Therefore, clarity and precision in scientific writing are essential throughout the drafting process.

Every statement, from endpoint definitions to procedural instructions, must be direct and unambiguous. This involves using clear language, avoiding unnecessary jargon, and providing explicit definitions for all study-specific terminology.

For example, instead of stating that adverse events will be "managed appropriately," a well-written protocol will specify the exact grading criteria (e.g., CTCAE v5.0), reporting timelines, and required follow-up procedures. This level of detail minimizes interpretive variance at the site level.

A protocol must be written with enough clarity that an experienced investigator at a new site, without prior knowledge of the study, can execute it correctly based solely on the document's content.

A logical structure, consistent formatting, and a detailed table of contents are not merely stylistic choices; they are functional elements that enhance the document's accessibility and navigability for reviewers.

Implementing a Structured, Iterative Review Cycle

Once an initial draft is complete, a structured review cycle should commence. The objective is to systematically collect and integrate feedback from the cross-functional team. A chaotic review process, such as sending a draft to multiple reviewers simultaneously without a clear consolidation plan, often results in conflicting feedback and delays.

A controlled, sequential review process is a more effective approach:

- Core Team Review: The central protocol team (medical, statistical, and operational leads) conducts an initial review to ensure the draft aligns with the study's core objectives and design principles.

- Extended Team Review: The draft is then distributed to the wider team, including regulatory affairs specialists, data managers, and selected investigators, for their specialized input.

- Feedback Reconciliation: A designated author or team lead consolidates all comments, identifies any conflicting suggestions, and facilitates a reconciliation meeting to resolve discrepancies and finalize revisions.

This structured workflow ensures all perspectives are considered while maintaining timeline control. It is also critical to maintain a complete audit trail of all changes and the rationale behind them to ensure inspection readiness. Effective document control is a core function of a regulatory document management system.

The Final Quality Assurance Check

Before a protocol is considered final, it must undergo a thorough quality assurance (QA) or quality control (QC) check. This step is distinct from scientific review; it is a meticulous verification of the document's internal consistency and its alignment with other key study documents.

This final QA check should confirm:

- Internal Consistency: All references to endpoints, visit schedules, and procedures are consistent throughout the document.

- Cross-Document Alignment: The protocol aligns with related documents, particularly the Investigator's Brochure (IB) and the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP). For example, safety reporting requirements in the protocol must be consistent with the known risks detailed in the IB.

- Regulatory Compliance: The document is checked against applicable guidelines, such as ICH E6, to ensure all required sections and information are present.

This final verification step helps identify and correct errors and inconsistencies that could lead to questions or delays during IRB or health authority review, resulting in a high-quality, submission-ready protocol.

Managing Protocol Amendments and Version Control

A clinical trial protocol is a dynamic document that may require updates as a study progresses. New safety information, operational challenges, or interim analysis results may necessitate changes.

The process of implementing these changes through formal protocol amendments, coupled with rigorous version control, is a critical component of Good Clinical Practice (GCP). It is a regulated process designed to protect participant safety and maintain the scientific integrity of the trial.

Any proposed change must be formally justified, reviewed, and approved before implementation. The workflow for creating an amendment mirrors that of the initial protocol, following a structured cycle of drafting, review, and quality control.

This iterative process ensures that every modification is thoroughly vetted before being implemented at clinical sites.

The Formal Amendment Process

When a change is required, it must be classified based on its potential impact, which determines the necessary regulatory actions.

-

Substantial Amendments: These are changes that could significantly affect the safety or well-being of participants, the scientific value of the trial, or the conduct of the study. Examples include modifying the primary endpoint, altering inclusion/exclusion criteria, or changing the dosage of the investigational product. Such amendments require formal submission to and approval from regulatory authorities (FDA, EMA) and relevant Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or Ethics Committees (IECs) prior to implementation.

-

Non-substantial Amendments: These are minor corrections or administrative clarifications that do not impact patient safety or the study's scientific validity, such as correcting a typographical error or updating contact information. While these typically do not require pre-approval from regulatory authorities, they must be documented and communicated to relevant parties according to established Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs).

The sponsor is responsible for drafting the amendment package, which usually includes a summary of changes, a rationale for each change, and both clean and redlined versions of the protocol.

Maintaining a Complete Audit Trail

Version control is fundamental to amendment management. A robust system is necessary to ensure a complete and accurate history of the protocol is maintained for regulatory inspection. An inspector must be able to reconstruct the timeline of the trial and identify which version of the protocol was effective at any given time.

A core principle of version control is ensuring that all clinical sites are using the same, currently approved protocol version. Any deviation from this introduces unacceptable risks to both participant safety and data integrity.

This requires a clear versioning system (e.g., Protocol V1.0, Amendment 1 V2.0) and a comprehensive change log within the document. Each new version must be dated and formally signed off by the sponsor.

Once approved, an amendment and all related correspondence, including approval letters from regulatory authorities and IRBs, become part of the trial's official record. These documents must be properly filed within the Trial Master File. An electronic Trial Master File (eTMF) provides a centralized, secure, and auditable repository for this documentation.

Modern clinical documentation platforms can automate versioning, track changes, and manage electronic review and approval workflows. This controlled environment ensures that the correct document versions are distributed to the appropriate personnel in a timely manner, which is essential for maintaining GCP compliance and inspection readiness.

Adapting Protocols for Modern Clinical Trial Designs

The traditional, static clinical trial protocol is evolving to accommodate innovative trial designs, such as decentralized clinical trials (DCTs) and adaptive studies. This requires a shift in how protocols are developed, with a greater emphasis on building in flexibility and addressing new operational complexities from the outset.

The pace of clinical development is accelerating. One report noted 6,071 Phase I-III interventional trials were initiated globally in the first half of a single year, a 20% increase from the previous year and higher than pre-pandemic levels. Further details are available in the mid-year clinical trial insights on Anjusoftware.com.

In this competitive environment, designing efficient and flexible trials is a necessity.

Incorporating Decentralized Clinical Trial Elements

The inclusion of decentralized elements, such as remote monitoring or direct-to-patient shipment of investigational products, introduces new operational complexities that must be addressed in the protocol.

A protocol for a DCT or hybrid trial must provide detailed specifications for these new modalities:

- Remote Data Collection: The protocol should identify the specific electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) tools or wearable devices to be used, outline the data flow, and define the data validation processes.

- Home Health Visits: It must be explicit about the scope of activities permitted for home health nurses, including required training and certifications.

- Investigational Product Logistics: The plan for managing the chain of custody for investigational products shipped directly to patients, including procedures for handling and documenting temperature excursions, must be detailed.

Ambiguity in these areas can lead to operational inconsistencies that compromise both participant safety and data integrity.

Structuring Protocols for Adaptive Designs

Adaptive trials allow for pre-specified modifications to a study based on interim data, potentially leading to more efficient trial outcomes. However, this flexibility must be rigorously controlled, with all potential adaptations defined in the protocol before the study begins.

An adaptive design protocol must pre-specify all potential modifications. The document must serve as a comprehensive plan, detailing which adaptations are permissible, the statistical triggers for implementing them, and the procedures for doing so without introducing bias.

A well-designed adaptive protocol will clearly define elements such as:

- Sample Size Re-estimation: It must specify the timing of the interim analysis and the pre-defined statistical rules that will govern any decision to increase or decrease the sample size.

- Arm Dropping: It must define the futility or efficacy boundaries that, if crossed by a treatment arm, will trigger its discontinuation as per a pre-specified plan.

This level of detail is required by regulatory authorities like the FDA and EMA, who need assurance that any adaptation is a planned component of the scientific investigation and not an ad-hoc decision. Developing protocols that can accommodate these modern complexities is now a core competency for sponsors and CROs.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following are answers to common questions regarding protocol development for clinical trials.

What is the difference between a clinical trial protocol and a Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP)?

The clinical trial protocol is the overarching document that describes the "what" and "why" of the study. It outlines the scientific objectives, study design, methodology, and primary endpoints.

The Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) is a separate, more detailed technical document that describes the "how" of the data analysis. It provides explicit, step-by-step instructions for the biostatistics team on how to execute the analyses summarized in the protocol. The SAP is typically finalized before the clinical database is locked to prevent analysis bias.

How frequently should a protocol be amended?

There is no predetermined schedule for protocol amendments. An amendment is initiated only when necessary, driven by changes that could substantially impact participant safety, data integrity, or the scientific objectives of the trial.

Common triggers for an amendment include:

- The emergence of new safety data from the ongoing trial or other relevant studies.

- Significant operational challenges, such as persistent low enrollment.

- New scientific evidence that affects the original study rationale.

Substantial amendments require formal review and approval by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committee (IEC) and, in many cases, by regulatory authorities before the changes can be implemented at study sites.

Who has the final approval authority for the protocol?

While the protocol is developed with input from a cross-functional team of medical, statistical, operational, and regulatory experts, the final approval authority rests with the trial sponsor.

The sponsor's final signature signifies that the organization assumes full responsibility for the scientific, ethical, and operational conduct of the study as detailed in the protocol. This approval is typically provided by a senior representative, such as the Chief Medical Officer, confirming that the protocol is finalized and ready for submission to regulatory authorities and ethics committees.