An informed consent form (ICF) template serves as a master document for generating all informed consent forms for a clinical trial program. It is a foundational document providing the required structure and pre-approved language to meet regulatory guidelines from bodies such as the ICH and FDA.

Once this standardized template is established, it can then be adapted for the specific requirements of each clinical trial protocol.

The Role of the ICF Template in Clinical Research

The Informed Consent Form (ICF) is a critical document establishing the ethical and legal foundation of a clinical trial. It functions as the primary communication tool between the research team and a potential participant, operationalizing the principle of subject autonomy.

The objective of the ICF is to provide a potential participant with sufficient information regarding the study's purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives to allow for a voluntary and informed decision about participation.

An informed consent form template is the standardized master version from which all study-specific ICFs are derived. An appropriate analogy is an architect's blueprint, which dictates essential, non-negotiable structural elements required for regulatory compliance and safety, while allowing for customization of study-specific details.

Differentiating Key Document Types

In clinical documentation, precise terminology is essential. It is important to understand the ICF lifecycle and the distinct terms used at each stage:

- Template: The standardized, quality-controlled master document. It contains all mandatory regulatory sections and standard language applicable across multiple studies.

- Draft: A version of the template that has been populated with the specifics of a particular clinical trial protocol, including the study's purpose, procedures, specific risks and benefits, and other relevant details.

- Final Document: The completed, study-specific ICF that has been reviewed, finalized, and approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committee (EC) for use with trial participants.

This staged approach ensures that every ICF originates from a compliant foundation while incorporating the unique details required by each protocol.

Navigating Complexity and Regulatory Demands

A key challenge in ICF development is creating a document that satisfies global regulations while remaining comprehensible to a layperson. Under 21 CFR Part 50, the FDA mandates that investigators must obtain legally effective informed consent before a participant is enrolled in a trial.

However, analyses of existing ICFs often find that they contain complex legal and technical jargon, which can impede participant understanding. These documents can extend to 20-30 pages, potentially undermining a person's ability to fully comprehend the information presented.

A well-structured template is a primary tool for mitigating this issue. It provides a framework that aligns with core guidelines such as Good Clinical Practice (GCP). For further operational context, reviewing resources on ICH E6 GCP can offer valuable context regarding the principles of ethical trial conduct. Ultimately, an effective template is the first step toward producing a final ICF that is both compliant and understandable.

Building a Compliant ICF Template Block by Block

Developing a robust informed consent form template involves structuring a clear, transparent, and regulatory-sound document. Each section serves as a foundational component. A well-constructed foundation ensures the document can withstand the scrutiny of IRB or health authority review.

Both ICH E6(R3) and the FDA’s 21 CFR Part 50 outline the essential elements that every ICF must contain. The objective is to provide a potential participant with all necessary information to make an informed decision. The following sections describe how to structure a template to meet this objective.

The document workflow typically progresses from a master template to a study-specific draft, which then becomes the final, approved ICF.

Utilizing a high-quality template as a single source of truth ensures that each new ICF begins from a state of compliance and consistency, which can prevent operational issues during study conduct.

Foundational Elements of the ICF

The initial sections of the ICF are critical for establishing context and clarity. Their purpose is to immediately and clearly explain the nature of the activity.

- Statement of Research: The document must explicitly state that the activity involves research. This distinction is crucial for differentiating the study from standard medical care, a key concept for participant comprehension.

- Purpose of the Research: This section should explain, in plain language, the reason the study is being conducted. It should describe the research question, the investigational product (drug or device), and the condition under investigation.

- Duration and Procedures: This section outlines the participant's involvement from start to finish. It should detail the study duration, the schedule of visits, and all tests and procedures involved. It is mandatory to explicitly identify any procedures that are experimental.

Describing Risks and Benefits

This section of the ICF is a primary focus for both participants and IRBs. Complete transparency is required.

A realistic and balanced presentation of risks and benefits must be provided. Potential benefits should not be overstated or guaranteed. All reasonably foreseeable risks must be described without causing undue alarm.

A description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts is a required element. This includes not only physical side effects but also potential psychological, social, or other discomforts. Concurrently, any potential benefits to the participant or to others that may reasonably be expected from the research must be described.

A critical regulatory requirement is that the ICF cannot contain any exculpatory language. This prohibits the inclusion of any wording that suggests the participant is waiving legal rights or releasing the investigator, sponsor, or institution from liability for negligence.

Disclosures and Participant Rights

In addition to study procedures, the ICF template must cover several vital disclosures and articulate participant rights. These sections function as safeguards for participant autonomy.

This part of the informed consent form template is designed to build trust through transparency. For complex trials, these details often align with information presented in the main study plan; our guide on creating a clinical trial protocol template provides further information on that document's structure.

Key required disclosures include:

- Alternative Treatments: Participants must be informed of any appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment that may be available to them outside of the study.

- Confidentiality: The ICF must explain the extent to which confidentiality of records identifying the subject will be maintained and note the possibility that regulatory agencies may inspect the records.

- Voluntary Participation: The document must state that participation is voluntary, refusal to participate will involve no penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled, and the subject may discontinue participation at any time without penalty or loss of benefits.

- Contact Information: The ICF must provide contact information for answers to pertinent questions about the research, research subjects' rights, and in the event of a research-related injury.

By systematically assembling a template with these core components, an organization can produce a document that not only meets regulatory requirements but also fulfills its primary function: enabling individuals to make an informed decision.

Taking Your Clinical Trial Global: How to Adapt Your Consent Template

Conducting a clinical trial in multiple countries introduces additional complexity into the informed consent process. A single ICF is rarely suitable for global use without adaptation. To ensure efficient study startup and maintain compliance, sponsors must navigate a complex landscape of regional and national regulations.

An effective approach for a global trial is to develop a master template that is both standardized and flexible. This provides a controlled foundation that maintains consistency for critical information across all sites while accommodating specific modifications required by local ethics committees and regulatory agencies.

Finding the Balance: Harmonization vs. Localization

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) provides a common framework. Its Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines are recognized by the European Union, Japan, and the United States, among others, and help standardize the core content of a global ICF template.

However, ICH guidelines do not supersede local regulations. Each country, and sometimes specific regions within a country, may have unique requirements that must be followed. The operational challenge is to build a template that can incorporate these local requirements without compromising the document's fundamental structure.

A well-designed global informed consent form template anticipates this by including clearly delineated sections for localization. This practice helps prevent the operational challenges associated with managing numerous disparate document versions, which can complicate version control and Trial Master File (TMF) management.

A Quick Tour of Key Regional Requirements

Regulatory bodies worldwide have different areas of emphasis regarding the protection of participants and their data. Awareness of these differences is key for sponsors and CROs to avoid delays in study approval.

- European Union (EU): With the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in effect, data privacy is a primary concern. An ICF used in an EU member state must be explicit about how a participant’s personal data will be collected, used, stored, and protected, including details on data transfers outside the EU.

- United States (US): While the FDA’s regulations (21 CFR Part 50) align with ICH standards, local Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) frequently have their own specific language requirements, such as particular wording regarding compensation for study-related injuries or institutional contact information.

- Asia-Pacific Region: This region is highly diverse from a regulatory and cultural perspective. Local ethics committees may require specific cultural or linguistic adaptations to the form to ensure it is fully comprehensible to the local participant population.

The objective is not to create a single document that is universally applicable without modification. Rather, the goal is to build a master template that covers approximately 80% of global requirements, with clear instructions and placeholders for the remaining 20% that requires local adaptation.

Are You Running a Device or Drug Trial? It Matters.

The type of investigational product also influences ICF content. A common operational error is adapting a drug trial ICF for a medical device study without sufficient modification. For example, the presentation of risk information often differs. In up to 70% of device trials, risk information is derived from literature on similar devices rather than from established safety data on the specific device being studied—a distinction that must be made clear to participants. You can learn more about these findings on ICFs for medical devices to understand the importance of tailored templates.

Ultimately, an effective global strategy begins with a well-structured, modular template. This empowers clinical operations teams to efficiently create compliant, site-specific consent forms by respecting both global standards and local requirements, thereby minimizing compliance risk and costly delays.

Writing an ICF That Participants Can Actually Understand

Meeting regulatory requirements is the baseline for an acceptable ICF. The primary purpose of the document is to ensure a potential participant can genuinely understand the research before consenting. If the document is so technical or dense that it fails this objective, it has not fulfilled its core ethical duty.

The effectiveness of an informed consent form template is measured by its ability to translate complex regulatory and scientific language into a format that a layperson can read, process, and use to make an informed decision. This requires a shift in focus from writing for regulators to writing for participants, applying principles of effective medical writing and health literacy.

Adopting a Participant-First Point of View

Effective ICFs are often written from the participant's perspective. They avoid institutional jargon and legalese in the opening sections. Instead, they immediately address key questions a participant might have, such as "What is this study about?" and "What will happen to me if I take part?"

This framing can transform the document from a legalistic contract into a more accessible, conversational guide. It helps build trust and establishes a respectful tone that should be maintained throughout the informed consent process.

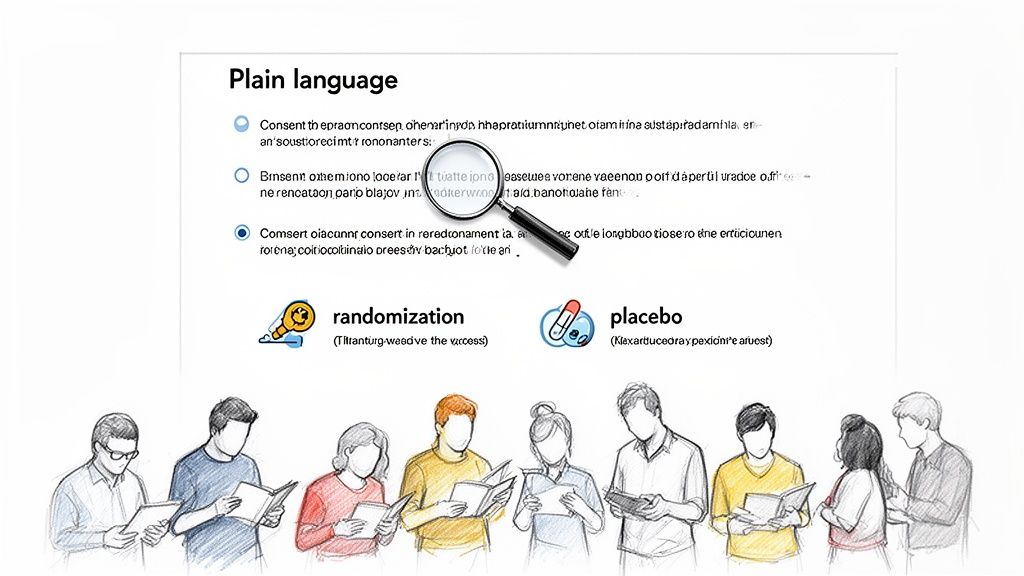

Using Plain Language to Explain Complex Concepts

Scientific concepts frequently present the greatest comprehension challenges. The medical writer's task is to find clear, simple ways to explain these ideas without sacrificing accuracy.

- Randomization: Instead of stating, "You will be randomized," an analogy can be more effective: "A computer will assign you to a study group by chance, similar to flipping a coin. This method helps ensure the groups are compared fairly."

- Placebo: Clinical terminology should be avoided. A practical explanation is preferable: "Some participants in this study will receive the investigational drug, while others will receive a placebo. A placebo looks identical to the drug but contains no active medicine. Neither you nor the study doctor will know which one you are receiving."

- Blinding: This concept can be explained in relation to the placebo: "This is a 'double-blind' study, which means that neither you nor the research team will know which group you are in. This design prevents expectations from influencing the study results."

The objective is simplification without loss of accuracy. Essential information must be conveyed in a manner that is accessible to individuals with varying levels of health literacy.

The Impact of Formatting on Readability

The presentation of information is as important as the choice of words. Effective formatting can significantly improve readability and comprehension. A well-designed informed consent form template should incorporate these principles.

Consider these formatting techniques:

- Short Paragraphs: Limiting paragraphs to two or three sentences creates white space and reduces the appearance of a dense "wall of text."

- Clear Headings: Using direct, question-based headings (e.g., "What Are the Risks of Participating?") helps participants navigate the document and find specific information.

- Bulleted Lists: Procedures, risks, or rights are often easier to scan and comprehend when presented in bullet points rather than a long narrative paragraph.

- Simple Fonts: A clean, legible font such as Arial or Calibri should be used. A font size of at least 12-point is recommended for accessibility.

When plain language is combined with thoughtful design, the result is an ICF that does more than meet a regulatory requirement. It empowers individuals, respects their autonomy, and reinforces the ethical foundation of clinical research.

Handling Optional Consents in Your Template

Modern clinical trials often include optional sub-studies or the collection of biological samples for future research. While valuable for advancing science, these activities add complexity to the consent process. Permission for these additional components—such as genetic testing or long-term sample storage—must be obtained correctly.

Properly managing optional consents is a matter of respecting participant autonomy. Each individual must clearly understand what is required for the main study versus what is optional.

Think Modular: Building a Flexible Consent Form

An effective operational approach is to treat the main consent form as the core agreement covering the primary study. Optional research activities should be presented in separate, self-contained sections. This modular design makes it clear to the participant which elements are required for trial participation and which are not.

Each optional section should function as a mini-consent form, with its own clear explanation of the specific activity, associated risks and benefits, and separate signature and date lines. This structure leaves no ambiguity about the participant's decision for each optional component.

Common optional consents include:

- Future Use of Biosamples: Permission to store blood or tissue for unspecified future research.

- Genetic Testing: Permission to perform genetic analyses, which involves specific privacy considerations.

- Data Sharing: Consent to share de-identified data with other researchers or in public scientific databases.

- Sub-Study Participation: Enrollment in a smaller, related study that may involve additional visits or procedures.

The Golden Rule: Participation Must Be Truly Voluntary

A critical principle is that a participant's decision on optional research components cannot affect their eligibility for the main trial. The consent form must state this explicitly in plain language, for example: "You can decline to participate in this optional genetic research and still be a part of the main study."

Regulatory bodies and ethics committees (IRBs/ECs) scrutinize ICFs for any evidence of "bundled consent," where it appears a participant may feel pressured to agree to all components in order to enroll. Physically separating optional consents on the page is the clearest and most defensible method to demonstrate that each choice was made freely and independently.

Keeping It All Straight: Operations and Document Control

From an operational perspective, managing modular consents requires a robust document management system. The master ICF template should contain all possible optional modules. For a given study or site, only the version with the relevant modules should be deployed.

This requires stringent version control. Your Trial Master File (TMF/eTMF) must clearly document which version of the ICF—including all optional components—was approved by the IRB and signed by each participant. Meticulous record-keeping is essential for audit-readiness and for verifying appropriate permissions for all samples and data.

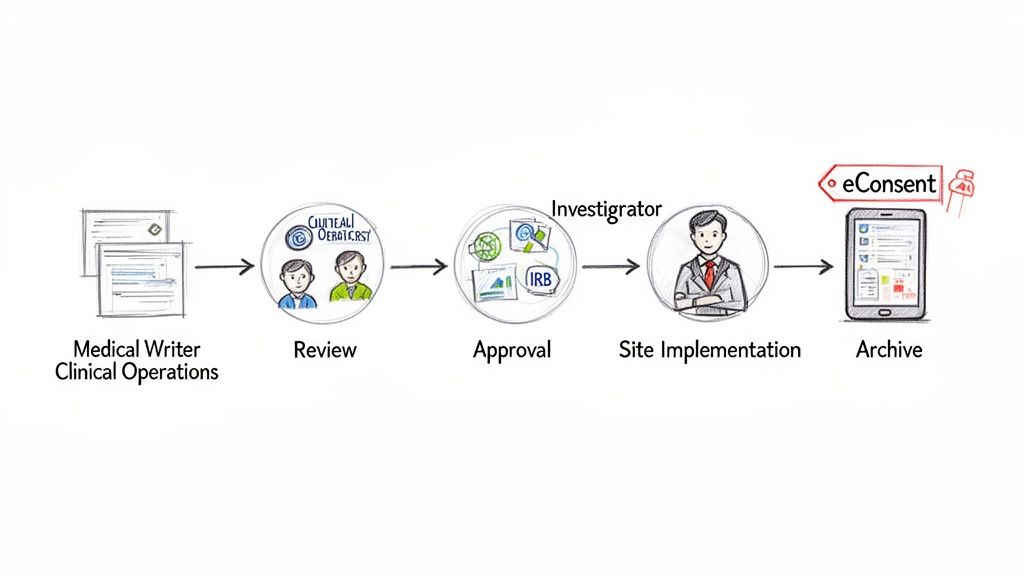

Bringing an ICF from Template to an Approved Document

An informed consent form begins as a template and evolves into a study- and site-specific document ready for participant use. The process of advancing an ICF from a draft to a final, IRB-approved version requires careful workflow management, defined roles, and robust version control.

The lifecycle typically begins when a medical writer or regulatory specialist populates the master informed consent form template with details from the study protocol. The resulting draft then undergoes a series of reviews by various functional area experts.

The Key Players in the ICF Review Process

Finalizing an ICF is a collaborative process. Each stakeholder provides a critical perspective to ensure the final document is accurate, operationally feasible, and ethically sound.

- Medical Writers: Responsible for drafting the initial document, ensuring the language is clear, comprehensible, and meets health literacy standards and regulatory requirements.

- Clinical Operations: Reviews the ICF from a practical, site-level perspective to confirm that descriptions of procedures, visit schedules, and participant tasks are accurate and feasible.

- Regulatory Affairs: Ensures the document complies with all applicable regulations, from ICH guidelines to specific FDA or EMA requirements.

- Principal Investigators (PIs): Provides final clinical review and approval, verifying the accuracy of all medical information, including procedures, risks, and potential benefits.

This review process is typically iterative, involving cycles of feedback and revision until all stakeholders agree the document is ready for submission to an IRB or Ethics Committee.

Version Control: Keeping Track of Changes and Amendments

Clinical trial protocols can be amended during a study. When a protocol is amended, the ICF must be updated accordingly to reflect any changes to procedures, risks, or other relevant information. This action re-initiates the review and approval cycle. Consequently, meticulous version control is not just a best practice—it is a regulatory necessity.

A cardinal rule of GCP is that only the most current, IRB-approved version of the ICF may be used to consent new participants. Using an outdated version is a significant compliance deviation.

Every version of the ICF, from the initial draft through all approved amendments, must be tracked and archived in the Trial Master File (TMF/eTMF). A high-quality regulatory document management system is essential for maintaining a complete, auditable history of each document and its approval status.

The Move to Electronic Informed Consent (eConsent)

The clinical research industry is increasingly adopting digital technologies, including for the consent process. Electronic informed consent (eConsent) platforms offer a more dynamic and traceable method for managing the ICF. In the US, eConsent systems are subject to regulations such as 21 CFR Part 11, which outlines requirements for electronic records and signatures.

This digital transformation has demonstrated benefits. The use of electronic systems with structured templates can streamline the consent process in global trials. The FDA has encouraged the use of digital health technologies in clinical trials. Pilot projects have shown that participant comprehension can be significantly higher with eConsent compared to traditional paper-based forms. Platforms designed for 21 CFR Part 11 compliance can reduce errors and improve the integrity of the consent process. You can learn more about the potential of electronic informed consent to improve understanding in clinical trials.

Whether using paper or electronic formats, a well-managed document lifecycle, founded on a solid template, enables the ICF to effectively serve its purpose as the bedrock of ethical research.

Your Top Questions About ICF Templates, Answered

This section addresses common questions that arise when working with informed consent form templates in a regulated clinical research environment.

What's the Real Difference Between an ICF Template and a Site-Specific ICF?

The ICF template is the master document developed by the sponsor or CRO. It contains all core study information, standardized language, and required regulatory elements that must be consistent across all participating trial sites. It functions as the single source of truth for the study's consent content.

A site-specific ICF is a localized version of that template. The clinical site adapts the master template to its local context. This typically involves adding the institution's official name and logo, inserting contact details for the local Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committee (EC), and incorporating any other institution-specific required language.

Thus, the template ensures global consistency, while the site-specific ICF ensures local compliance and relevance.

How Do We Handle Translations for a Global Trial?

Managing translations is a critical process with a defined best practice. First, the primary language version of the ICF (typically English) is finalized and approved. This approved master document serves as the validated source for all subsequent translations.

The key quality control step is back-translation. After the ICF is translated into a target language, a second, independent translator who has not seen the original English document translates it back into English. This process is used to verify that the meaning, intent, and nuances of the original text were preserved in the translation.

Every translated version must be submitted to and approved by the relevant local IRB or EC before it can be used to consent participants.

The objective of translation and back-translation is to achieve conceptual equivalence. This ensures that a participant in one country receives the same quality and depth of information as a participant in another, enabling a truly informed decision regardless of language.

What Are the Most Common Reasons an IRB Rejects an ICF?

IRB or EC rejections can cause study delays, but they often result from a few common issues. A well-constructed ICF template can help mitigate these risks.

The most frequent reasons for an ICF to be rejected or returned for revision include:

- The Language is Too Technical: The form contains excessive scientific jargon and is written at a reading level too high for the general public. An 8th-grade reading level or lower is the commonly accepted standard.

- The Wording Feels Coercive: The language appears to unduly influence a potential participant's decision or implies that participation is not entirely voluntary.

- The Risk/Benefit Section is Vague: The description of reasonably foreseeable risks and potential benefits is not sufficiently clear, complete, or balanced.

- It Doesn't Match the Protocol: The procedures, timelines, or risks described in the ICF are inconsistent with the information in the clinical trial protocol. This is a common reason for rejection.