A Pharmaceutical Quality Management System (QMS) is a formalized system that directs and controls an organization’s activities to consistently meet both customer and regulatory requirements. It is a framework of processes, procedures, and responsibilities for achieving quality policies and objectives. The primary goals are to ensure patient safety and product efficacy through controlled, documented, and repeatable operational activities.

Defining the Role of a QMS in Clinical Development

In the context of clinical trials, the QMS provides the operational structure for managing quality. It is a documented system that provides the framework for managing the entire ecosystem of clinical trial documentation and processes—from the initial draft of a protocol to the final Clinical Study Report (CSR).

The purpose of a QMS is to establish a culture where quality is managed proactively rather than reactively. It creates a clear, verifiable audit trail for every decision, change, and action taken during a study. This systematic approach is essential for demonstrating compliance to regulatory bodies such as the FDA and EMA.

From Regulatory Mandate to Operational Backbone

The concept of a formal QMS in the pharmaceutical industry evolved from public health events that highlighted the need for stricter oversight. This led to a progression from foundational Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines in the 1960s to modern, risk-based frameworks like ICH Q10 (Pharmaceutical Quality System). Contemporary systems are built around risk management and a commitment to continual improvement.

A modern QMS provides the necessary infrastructure for critical clinical operations.

- Document Control: This ensures that all personnel are working from the latest, approved versions of essential documents like protocols, Investigator's Brochures (IBs), and informed consent forms, preventing the use of outdated information.

- Personnel Training: It provides a mechanism for documenting that every individual involved in a study is qualified and trained on relevant procedures, with records to support their competency.

- Change Management: When a protocol amendment or other significant change is necessary, the QMS provides a structured process to propose, evaluate, and implement it without introducing new risks.

- Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA): When deviations occur, this system is used to investigate the root cause and implement actions to prevent recurrence.

Distinguishing Guidance from Practice

It is important to distinguish between high-level regulatory guidelines and the operational practices of a QMS. Guidelines, such as those from the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), define what must be achieved—for example, ensuring data integrity. The QMS, through its Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), defines how an organization will meet those requirements.

A well-designed QMS translates regulatory expectations into actionable, repeatable workflows. It transforms the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) into the tangible reality of a well-controlled clinical trial.

Ultimately, a robust pharmaceutical QMS is more than a tool for compliance. It serves as a strategic asset that supports efficiency, mitigates risk, and builds a foundation of trust with regulators. It is the framework that enables the management of complex drug development processes, ensuring that trial data is reliable and patient safety remains the primary focus.

Understanding the Regulatory Framework for Pharma QMS

A pharmaceutical QMS is based on a set of global regulations designed to protect patients and ensure the integrity of clinical data. These regulations serve as the blueprint for clinical development programs, outlining the minimum requirements for quality and compliance.

The purpose of this regulatory framework is to establish a common standard for quality, ensuring that a clinical trial conducted in one region can be confidently reviewed by regulators in another. For sponsors, CROs, and biotech companies, understanding these regulations is the first step toward building an effective QMS.

Core Guidelines Shaping Modern Pharmaceutical QMS

Several key international standards form the foundation of any modern pharmaceutical QMS. While they have different areas of focus, they are complementary and create a unified set of expectations for quality.

-

ICH Q10 (Pharmaceutical Quality System): This guideline provides a model for a quality system that extends across the entire product lifecycle, from development through post-market activities. It emphasizes management responsibilities, continual improvement, and performance monitoring, extending beyond basic manufacturing practices.

-

ICH E6(R3) (Good Clinical Practice): This is the international ethical and scientific quality standard for clinical trials. The latest revision, E6(R3), emphasizes a risk-based approach, encouraging sponsors to develop systems that proactively identify, assess, and mitigate risks to critical trial aspects, namely data integrity and participant safety.

-

FDA 21 CFR Part 11: This regulation defines the criteria under which electronic records and electronic signatures are considered equivalent to paper records and handwritten signatures. Any electronic system used for GxP-regulated clinical documents (e.g., an eTMF) must be compliant. This requires technical controls such as audit trails, system validation, and user access controls.

The need to adhere to these regulations has driven the adoption of supporting technologies. The global market for pharmaceutical quality management systems (PQMS) was valued at USD 1.81 billion in 2025 and is projected to grow at a 13.1% CAGR through 2033. This growth reflects the industry's need for advanced tools to meet regulatory demands. An insightful market report provides further detail on these trends.

From Regulation to Real-World Clinical Operations

These regulations directly influence the conduct of clinical trials and the management of associated documentation. A well-designed QMS translates these high-level requirements into specific, repeatable operational tasks.

For example, a protocol amendment triggers a series of actions governed by regulatory requirements. The modification must be formally documented through a change control process (ICH Q10), communicated to all investigators and sites (ICH E6), and all related electronic activities must be recorded in an unalterable audit trail (21 CFR Part 11).

A compliant QMS operationalizes regulatory requirements. It ensures every protocol version, Investigator's Brochure update, and signed informed consent form is managed within a system that is controlled, traceable, and inspection-ready.

This framework mandates that quality must be designed into every process, from the initial draft of a protocol to the final clinical study report. For any organization seeking regulatory approval from bodies like the FDA or EMA, demonstrating a functional, compliant QMS is a fundamental requirement.

The Core Components of an Effective Pharmaceutical QMS

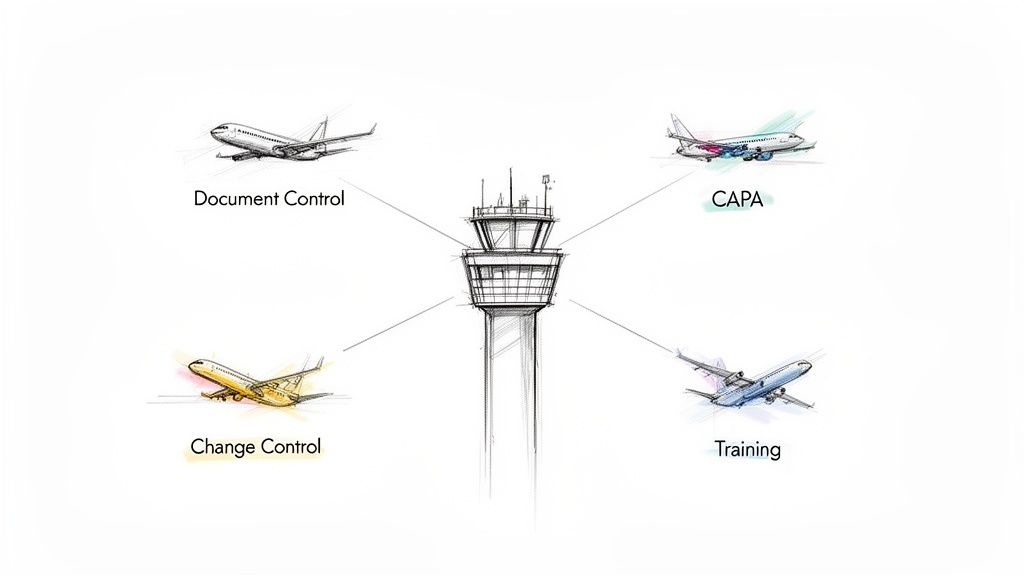

A pharmaceutical quality management system functions like an air traffic control system for a clinical trial. It provides the systems, rules, and oversight to guide operational activities with precision, ensuring a controlled process from study initiation through regulatory submission.

Each component is part of an interconnected system designed to manage complexity, prevent errors, and maintain a state of control.

These components are the operational pillars that support the daily work of clinical teams. Understanding how they function individually and collectively is essential for maintaining compliance and data integrity.

Document and Record Control

At the center of a QMS is Document Control, the systematic process for managing all GxP-regulated documents from creation to archival. Its primary function is to ensure that only the current, approved version of a document is in use.

Operationally, this prevents a clinical site from using an outdated protocol or an obsolete informed consent form—errors that could compromise patient safety and data validity. Effective document control provides a complete, auditable history of every version, review, approval, and distribution.

This process establishes a single source of truth for all critical study materials. Without it, a clinical trial lacks operational control, making it difficult to reconstruct study conduct for a regulatory inspection.

Change Control Management

Clinical trials are dynamic. Change Control is the formal process used to propose, assess, approve, and implement any modification to a validated system, process, or document.

This is a critical risk management tool that requires a team to evaluate a proposed change, such as a protocol amendment or an update to the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP). The process ensures the potential impact on patient safety, data integrity, and regulatory compliance is fully considered before implementation. A well-defined change control process ensures that modifications are deliberate and traceable.

Deviation and Non-Conformance Management

Despite careful planning, deviations from established procedures can occur. Deviation Management is the system for identifying, documenting, and investigating any such departures.

A deviation can range from a minor issue, like a missed signature, to a major event, like a dosing error. The QMS provides a structured workflow to:

- Document the Event: Capture what happened, when, and who was involved.

- Assess the Impact: Determine the potential effect on study integrity or patient safety.

- Investigate the Root Cause: Identify the underlying reason for the deviation.

This structured approach transforms unexpected events into opportunities for process improvement.

Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA)

Following directly from deviation management, the Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA) process is the problem-solving component of a QMS. It is how an organization formally addresses quality issues to prevent their recurrence.

- Corrective Action addresses the immediate problem identified during a deviation or audit.

- Preventive Action aims to eliminate the root cause of a potential problem before it occurs.

A robust CAPA system is an indicator of a mature QMS. Large pharmaceutical companies account for over 50% of the QMS software market, reflecting their need for integrated systems to manage complex processes like CAPA, electronic SOPs, and deviation tracking across global operations. The full pharmaceutical quality management software report provides additional market analysis.

The following table shows how these processes directly safeguard clinical documents.

Key QMS Processes and Their Role in Clinical Documentation

| QMS Process | Core Function | Impact on Clinical Documents (e.g., Protocol, CSR) | Regulatory Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| Document Control | Manages the document lifecycle (creation, review, approval, distribution, archival). | Ensures only the current, approved protocol version is used by sites. Provides a full version history for the CSR. | FDA 21 CFR Part 11, ICH E6 (R2) Section 8 |

| Change Control | Provides a formal process to evaluate and approve modifications to documents or systems. | Manages protocol amendments systematically, ensuring impact analysis and traceable approval before implementation. | ICH E6 (R2) Section 5.5.3 |

| CAPA | Investigates root causes of quality issues and implements actions to prevent recurrence. | If a CSR has recurring data errors, a CAPA would fix the process (e.g., update templates, add QC steps). | FDA 21 CFR 820.100, ICH Q10 |

| Training | Ensures personnel are qualified and trained on relevant procedures (SOPs). | Verifies that authors and reviewers of a protocol or CSR are trained on the relevant SOPs before performing their tasks. | ICH E6 (R2) Section 2.8, FDA 21 CFR 211.25 |

This table illustrates that a QMS is not a separate administrative layer but the framework that ensures the reliability, accuracy, and defensibility of the documents supporting a clinical program.

Training and Competency Management

A QMS is only effective if the personnel using it are competent. Training Management is the system that ensures every team member is qualified, competent, and properly trained on the specific procedures and regulations relevant to their role.

This involves more than tracking course completion. It means documenting initial training, monitoring ongoing competency, and maintaining meticulous records that can be presented during an audit. For example, a medical writer must have documented training on the SOP for Clinical Study Report (CSR) development, while a clinical research associate requires proof of training on the current protocol and GCP guidelines. This system ensures the entire team operates from a shared, compliant knowledge base.

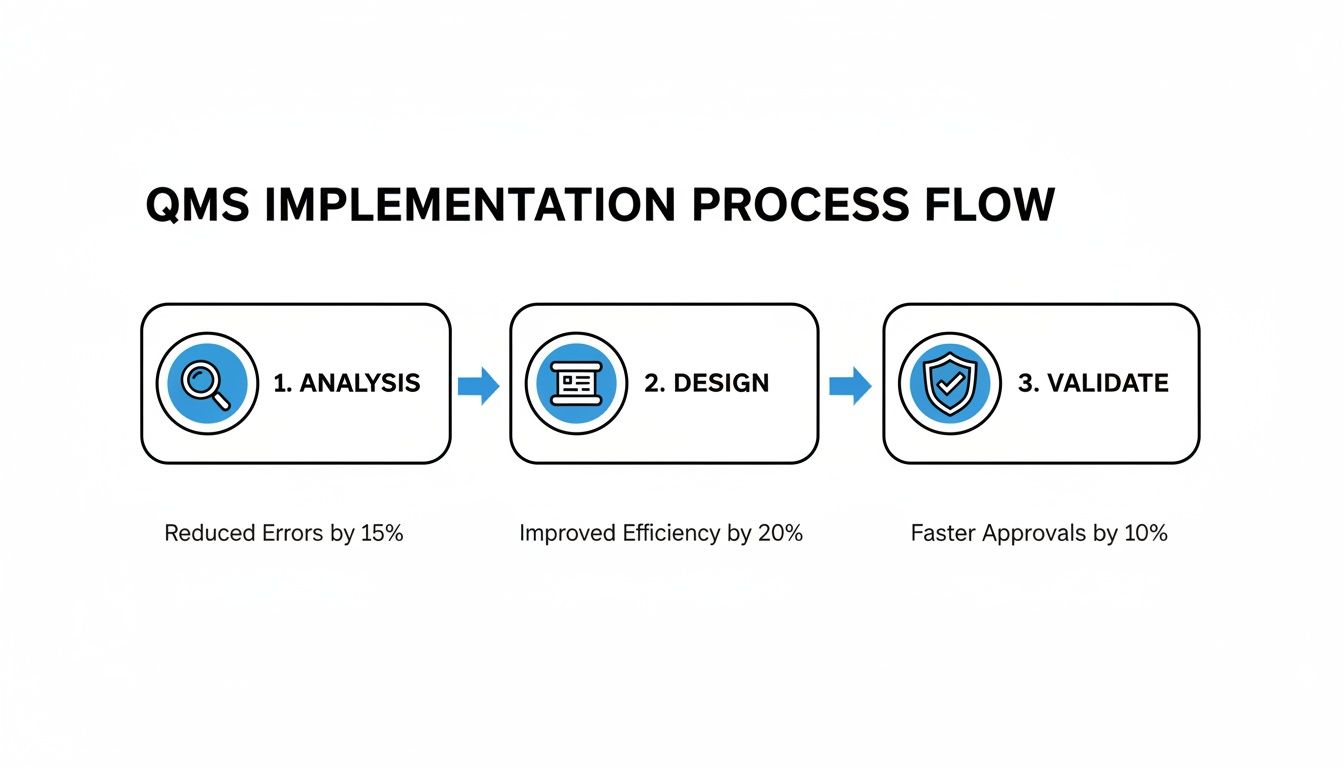

Getting Started: A Scalable QMS for Your Clinical Operations

Implementing a pharmaceutical quality management system should be a tailored process. A system designed for a large global sponsor would be inappropriate for an early-stage biotech with a single asset. The goal is to build a QMS that is fit-for-purpose.

This means the system should be scaled to the organization's current size, complexity, and risk profile, while also being designed to accommodate future growth. A phased, strategic approach based on a quality-by-design (QbD) mindset is recommended. Instead of treating quality as a final inspection point, QbD integrates quality principles into clinical processes from the outset. This proactive approach makes the QMS a strategic tool rather than an administrative burden.

Phase 1: The Foundational Assessment and Gap Analysis

The first step is to understand the current state. A thorough gap analysis provides a clear picture of existing strengths and weaknesses relative to regulatory expectations.

During this phase, the following activities are typical:

- Map Your Current Processes: Document existing workflows for key activities, such as document creation and approval, training management, protocol amendment processing, and investigator qualification.

- Review Applicable Regulations: Identify all regulations and guidelines relevant to your operations, such as ICH E6 and 21 CFR Part 11.

- Pinpoint the Gaps: Compare current processes to regulatory requirements to identify areas of non-compliance and risk. Examples include inconsistent document versioning, a lack of formal training records, or informal change control processes.

This initial analysis serves as the blueprint for the implementation plan, allowing for the prioritization of resources on the highest-risk areas.

Phase 2: Designing Processes and Writing Your SOPs

With a clear understanding of the gaps, the next phase involves designing future-state processes. This is accomplished by developing Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) that translate high-level principles into concrete, daily actions.

SOPs should be clear, concise, and written for the end-user. They must define the "who, what, when, where, and why" for each core QMS process. An SOP for eTMF management, for instance, would detail the exact steps for document upload, QC, indexing, and archival. This creates the operational rulebook for the team.

A well-written SOP is not just a compliance document; it is a practical guide that promotes consistency and reduces ambiguity in daily work. It is the mechanism for turning regulatory theory into repeatable, auditable action.

Phase 3: Evaluating Technology and Validating Your Systems

Modern clinical trials rely on technology. Selecting the right systems—such as an eTMF, a learning management system (LMS), or an electronic QMS (eQMS) platform—is a critical decision.

Key considerations include:

- Scalability: Can the system support both current and future operational needs?

- Compliance: Does the vendor provide a comprehensive validation package and demonstrate an understanding of requirements like 21 CFR Part 11?

- Integration: Does the system integrate with other clinical systems, such as a CTMS or EDC, to avoid manual data re-entry?

After selection, a system must undergo formal Computer System Validation (CSV). This is a required step that produces documented evidence that the system functions as intended and meets all regulatory requirements. The management of these platforms is a specialized discipline; the complexities of a regulatory document management system offer a detailed example.

Phase 4: Training and Rollout

The final phase is implementation. A QMS is only effective if its users are proficient. A well-planned rollout with comprehensive training is essential.

Training should be tailored to different roles and should cover not only the technical "how-to" aspects of the system but also the "why" behind the quality principles. When the team understands the connection between their actions, patient safety, and data integrity, the QMS becomes an integrated part of the organizational culture.

Integrating Your QMS with Clinical Documentation Workflows

A pharmaceutical QMS realizes its full value when it is integrated into the daily workflows of creating, reviewing, and finalizing clinical trial documents. For medical writers, clinical scientists, and regulatory professionals, the QMS should be a practical tool that guides their work, not an abstract corporate requirement.

This integration connects quality objectives to the tangible work of managing protocols, Clinical Study Reports (CSRs), and Statistical Analysis Plans (SAPs). A successful integration ensures that the lifecycle of every key document—from first draft to final regulatory submission—is controlled, consistent, and audit-ready.

From Document Draft to Submission-Ready Asset

The lifecycle of a clinical document involves multiple authors, reviewers, and approvers. Without a QMS, this process can become disorganized and reliant on emails and shared drives. A QMS provides structured pathways for these critical workflows.

- Document Control and Versioning: This is a fundamental requirement to ensure that all team members are using the current version of a document. Using an outdated protocol amendment, for example, could compromise patient safety and data integrity.

- Audit Trails for Data Integrity: As required by regulations like 21 CFR Part 11, all actions performed on an electronic document must be logged. A secure, computer-generated, time-stamped audit trail provides verifiable proof of who did what and when.

- Change Control for Amendments: When a protocol is amended, a formal change control process provides a systematic method to assess the impact of proposed changes, obtain necessary approvals, and implement the change consistently across all sites.

The flowchart below outlines the core steps for implementing a QMS to support these documentation workflows.

This illustrates how a methodical approach—moving from analysis and design through to final validation—builds a system that is both compliant and operationally efficient.

Embedding Quality into Document Creation

Modern documentation platforms often integrate QMS principles directly into the authoring environment, rather than treating quality control as a separate, final step.

This means a medical writer drafting a CSR works within a system that enforces the correct template, automatically tracks version history, and captures electronic signatures within a validated workflow. The document is created in a compliant state from the beginning.

An integrated approach transforms quality management from a retrospective activity into a real-time, preventative function. It fosters consistency and audit readiness by design.

This type of integration is crucial for managing the Trial Master File (TMF). Every final, approved document, from the Investigator's Brochure to site visit reports, must be filed correctly in the TMF. A connected QMS ensures that any document filed in the TMF has a complete and verifiable history. For a closer look at this cornerstone of clinical trials, our guide on the structure and management of the Trial Master File provides more information.

Ultimately, this holistic system ensures that from creation to archival, every document is a reliable and defensible asset.

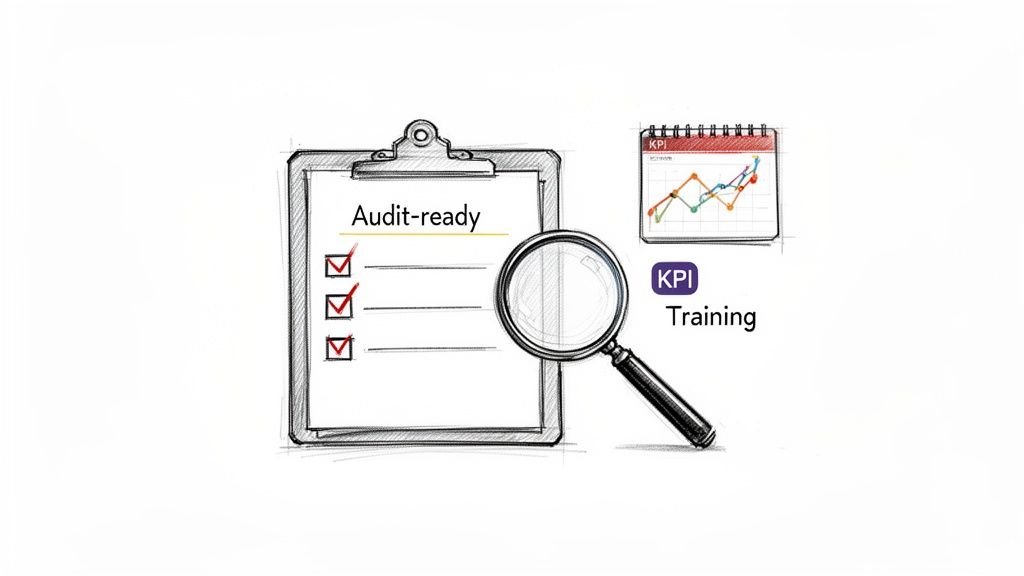

Maintaining an Audit-Ready QMS

A pharmaceutical QMS is not a one-time project; it is a dynamic component of operations that requires continuous maintenance. Being audit-ready is not about last-minute preparation for an inspection, but about fostering a culture where quality is integrated into daily work, ensuring a constant state of readiness.

The key to sustained readiness is measurement. By tracking relevant Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), an organization can monitor the health of its QMS in real-time. This data-driven approach shifts quality from a reactive to a proactive function, allowing for the identification and correction of weaknesses before they become audit findings.

Monitoring QMS Health with Key Performance Indicators

KPIs function as the vital signs of a quality system. They provide quantitative data on performance, turning abstract quality goals into concrete, measurable targets.

Essential KPIs for a pharmaceutical QMS include:

- CAPA Closure Rates: The time required to close Corrective and Preventive Actions. Increasing closure times may indicate process bottlenecks, insufficient resources, or ineffective root cause investigations.

- Deviation Trends: The frequency and type of recurring deviations. Tracking these trends can uncover systemic process flaws or training gaps.

- Training Compliance Metrics: The percentage of personnel who have completed required training on schedule. A metric below 100% is a significant compliance risk and indicates potential competency gaps.

These metrics provide the objective evidence needed for management review meetings, informing decisions about resource allocation and process improvement initiatives.

An Audit Readiness Checklist for Key Areas

Maintaining a state of readiness requires regular and rigorous self-auditing. A checklist can be a powerful tool for ensuring that critical components are consistently managed, documented, and prepared for inspection.

This is particularly important for ensuring the integrity of electronic records and systems. For more detailed information on system integrity, our guide on FDA 21 CFR Part 11 compliance is a useful resource.

Proactive internal auditing allows an organization to identify and correct issues on its own terms. It shifts the dynamic from preparing for an inspection to confidently demonstrating control over processes.

The following checklist outlines core areas to review, key questions to ask, and the types of evidence an auditor will expect to see. It can serve as a foundational tool for an internal audit program.

Audit Readiness Checklist for a Pharmaceutical QMS

| Audit Area | Key Questions to Ask | Example Evidence to Prepare |

|---|---|---|

| Documentation Access | Can staff readily access the current, approved version of any required SOP? | Live demonstration of navigating the electronic document management system (eDMS) to locate a specific document. |

| Training Records | Are the training records for all relevant personnel complete, signed, and current? | Presentation of a master training matrix with links to individual curricula and completion records. |

| Management Review | Is there documented evidence of regular management reviews of the QMS? | Signed meeting minutes showing review of KPIs, past audit findings, and open CAPAs. |

| Audit Trails | Can you produce a complete, unalterable history for a critical electronic document on demand? | Export of the full, time-stamped audit trail for a document such as a protocol, from creation to final approval. |

Regularly performing these checks helps embed audit readiness into routine business practices, ensuring the QMS remains robust, compliant, and effective.

Got Questions About Your Pharma QMS? We’ve Got Answers.

For those involved in the daily execution of clinical trials, the theory behind a pharmaceutical quality management system can sometimes feel disconnected from practical work. It is common for practical questions to arise. This section addresses some of the most frequent questions from clinical teams regarding roles, implementation, and maintaining audit readiness.

QA vs. QC: What’s the Real Difference?

These terms are often used interchangeably, but they represent two distinct and essential functions.

A useful analogy is building a house. Quality Assurance (QA) is the architect. QA designs the blueprint—the systems, SOPs, and training plans—to ensure the house is built correctly from the start, preventing problems before they occur. QA is process-oriented.

Quality Control (QC) is the on-site inspector. QC performs hands-on checks of the finished work—the foundation, wiring, and plumbing—to identify specific defects that require correction. QC is product-oriented.

In a clinical context:

- QA is responsible for ensuring a well-defined process exists for writing a Clinical Study Report (CSR) and that all relevant personnel are trained on that process.

- QC involves the detailed, line-by-line review of the final CSR to verify that all data and statements are accurate and consistent with the source data.

Both are necessary. QA builds quality into the process, while QC verifies the quality of the output.

How Can a Small Biotech Build a QMS Without Breaking the Bank?

For a small biotech or startup, implementing a large-scale, enterprise-level QMS is often not feasible. The approach should be lean, risk-based, and scalable.

Begin with the essential, highest-risk activities. Focus on creating clear, simple SOPs for these areas first. Typically, this includes document control, change control, and training management. Establishing these core processes builds a solid foundation.

The guiding principle for a small biotech is to create a QMS that is fit-for-purpose. Develop the core processes needed for compliance today, and select technology that can scale for future needs.

What Red Flags Do Auditors Look for in a QMS?

Regulators and auditors often focus on common areas of weakness during inspections. Understanding these areas can help in preparing for an audit.

Common findings include:

- Ineffective CAPAs: Documenting a corrective and preventive action (CAPA) is not sufficient. A common audit finding is a closed CAPA that lacks evidence of effectiveness—that is, proof that the corrective action truly solved the problem and that the preventive action will prevent recurrence.

- Inadequate Documentation Practices: This includes a wide range of issues, such as missing signatures or dates, use of outdated document versions, or incomplete training logs. To an auditor, these issues suggest a lack of fundamental process control.

- Weak Vendor Oversight: An organization is responsible for the quality of work performed by its vendors. Auditors frequently find that companies have not adequately qualified their CROs, software providers, or other critical partners, creating a significant compliance gap.