FDA 21 CFR Part 11 is the regulation that establishes the criteria under which the FDA considers electronic records, electronic signatures, and handwritten signatures executed to electronic records to be trustworthy, reliable, and generally equivalent to paper records and handwritten signatures executed on paper. For organizations in the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and CRO sectors, this regulation is a foundational component of managing clinical trial documentation where data integrity is paramount.

Understanding 21 CFR Part 11 in the Context of Clinical Trials

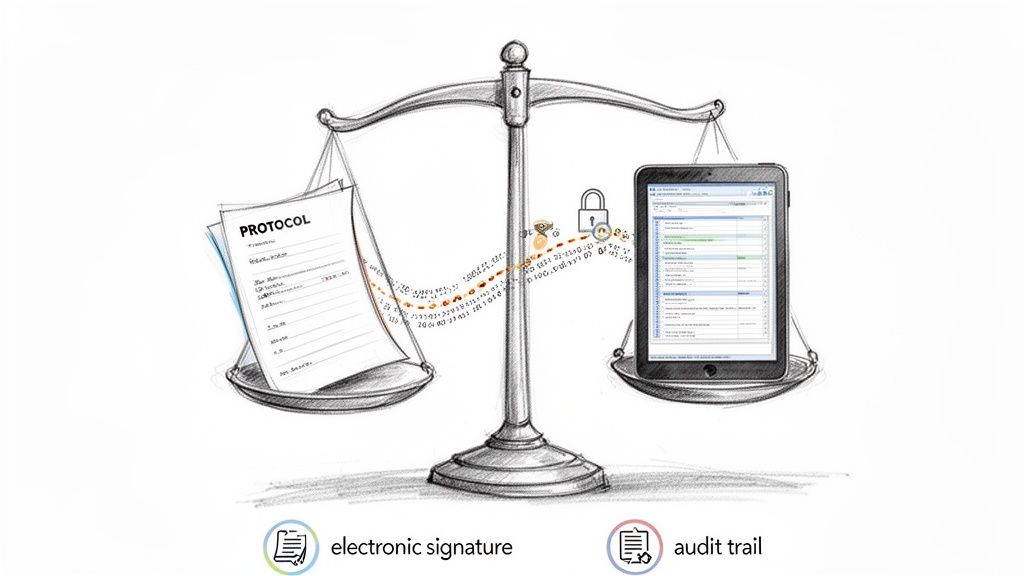

At its core, Part 11 was designed to provide the same level of confidence in electronic records as that of their paper-based counterparts. For professionals managing clinical documentation, the regulation is not an optional IT consideration; it is fundamental to operational processes and the ability to demonstrate compliance during regulatory inspections.

The regulation applies to electronic records that are created, modified, maintained, archived, retrieved, or transmitted under any records requirements set forth in agency regulations. This scope means Part 11 applies to a wide range of documents within the clinical development lifecycle, from the initial study protocol to the final clinical study report (CSR).

Defining Key Terms in an Operational Context

Effective implementation of Part 11 requires a practical understanding of its core terminology as it applies to daily clinical operations.

- Electronic Record: This term refers to any combination of text, graphics, data, audio, pictorial, or other information representation in digital form. In practice, this includes the final, approved versions of documents such as a protocol, an Investigator's Brochure (IB), or a CSR managed within a validated electronic system.

- Electronic Signature: This is a computer data compilation of any symbol or series of symbols executed, adopted, or authorized by an individual to be the legally binding equivalent of the individual's handwritten signature. When a designated individual applies their electronic signature, they are formally documenting their approval, review, or authorship of a specific record.

- Audit Trail: This is a secure, computer-generated, time-stamped electronic record that allows for the reconstruction of the course of events relating to the creation, modification, or deletion of an electronic record. For example, if a protocol is amended, the audit trail provides a complete history of that change.

When these controls are implemented correctly within a compliant system, a protocol that is electronically signed is considered as valid and traceable as one that was physically signed and filed.

The table below outlines the core components of Part 11, connecting the regulatory requirements to their purpose and practical application in documentation workflows.

Table: Key Components of 21 CFR Part 11 Compliance

| Requirement Category | Core Principle | Application in Clinical Documentation |

|---|---|---|

| System Validation | Trustworthiness | Providing documented evidence that a system consistently performs its intended function for managing records like protocols or IBs. |

| Audit Trails | Traceability | Automatically logging all actions performed on a CSR—who made the change, the date and time, and the reason for the change. |

| Electronic Signatures | Accountability | Securely linking an individual (e.g., Principal Investigator) to a specific action, such as signing a protocol amendment. |

| Access Controls | Security | Ensuring only authorized individuals can access or modify sensitive documents, such as those containing unblinded study data. |

| Records Retention | Durability | Guaranteeing that electronic CSRs and their associated audit trails remain accurate, complete, and retrievable throughout the required retention period. |

These elements function as an interconnected system designed to maintain the integrity of clinical data from creation through archival.

Open vs. Closed Systems

Part 11 distinguishes between two types of systems, which impacts the required security controls.

- A closed system is an environment in which system access is controlled by persons who are responsible for the content of electronic records that are on the system. An organization's internal, validated document management system is a common example.

- An open system is an environment in which system access is not controlled by persons who are responsible for the content of electronic records on the system. For instance, a web portal where investigators from multiple external sites upload documents. Such systems require additional security controls, like encryption, to protect records during transmission.

The first step toward compliance is risk assessment and determining the scope of application. Part 11 is not about validating every electronic file but about identifying which electronic records are subject to predicate rules and ensuring they are managed within a controlled, validated environment.

This regulation complements other critical standards, such as the guidelines from the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). While Part 11 provides the "how" for trustworthy electronic records, the broader principles of clinical trial conduct are outlined in resources like the ICH guidelines for clinical trials. A thorough understanding of both is foundational to modern, compliant clinical development.

The Technical Controls for Data Integrity

To apply FDA 21 CFR Part 11 in practice, specific technical controls must be implemented. These are not optional features but are foundational to ensuring data integrity. For those managing clinical trial documentation, these controls are what make a digital workflow suitable for regulatory submissions.

The primary objective is to create an environment where critical documents, such as a protocol or a Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP), are protected from unintentional or unauthorized alterations. This is achieved through a layered approach that combines robust audit trails with strict access controls, where every action is both authorized and recorded.

Establishing an Unalterable History with Audit Trails

A core requirement of Part 11 is the use of secure, computer-generated, time-stamped audit trails. This feature functions as the system's unchangeable log, recording the entire lifecycle of every electronic record.

A compliant audit trail must capture the "who, what, when, and why" for all actions that create, modify, or delete electronic records. Specifically:

- Who: The unique user ID of the individual performing the action.

- What: A description of the action, such as creation, modification, or deletion of a record.

- When: The date and time of the action, synchronized to a reliable time source.

- Why: The reason for a change, which provides critical context during a review or inspection.

These logs must be protected from modification or deletion by any user, including system administrators. During an inspection, regulators may review these trails to reconstruct a document's history and verify that all changes were authorized and documented. The system must also have the capability to generate accurate and complete copies of these audit trails in a human-readable format for review.

Enforcing Access with Logical Controls

Working in conjunction with audit trails are logical access controls. Their purpose is to prevent unauthorized system activities. These controls ensure that only authenticated individuals can access the system and that they can only perform actions aligned with their assigned roles and responsibilities. The cornerstone of this control is the enforcement of unique user credentials for every individual.

Shared accounts are inconsistent with Part 11 requirements because they obscure individual accountability. Each user must have a unique ID and a confidential password to establish a link between an action and a specific individual.

Beyond unique IDs, a compliant system must enforce strong password policies. This includes requirements for password complexity, periodic changes, and account lockout after a set number of failed login attempts. These measures are essential safeguards against unauthorized access to sensitive clinical data. The role of these controls is further detailed in resources covering electronic Trial Master File (eTMF) software.

Practical Example: Managing a Statistical Analysis Plan

Consider a biostatistics team finalizing a Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) within a Part 11-compliant platform. The technical controls protect the document's integrity at each stage:

- Drafting and Review: A medical writer drafts the initial SAP. The system’s role-based access control ensures only individuals with "author" or "reviewer" roles can modify or comment on the document. A project manager with "view-only" access can see the document but cannot alter its content.

- Executing a Change: The lead statistician revises a section defining the primary endpoint analysis. Upon saving the new version, the audit trail automatically logs their user ID, the date and time, the specific changes made, and prompts for a reason for the change, such as "Clarified handling of missing data per protocol amendment."

- Securing Approval: Once the SAP is finalized, it is routed for electronic signature. The Head of Biostatistics must enter their unique user ID and password to apply their signature. This signature is then cryptographically and permanently linked to that specific version of the document. The signature manifest also clearly states the meaning of the signature—for example, "approval."

In the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors, FDA 21 CFR Part 11 is a critical regulation for data integrity. Enacted in 1997, it requires systems managing data for quality or safety decisions to have controls like unalterable audit trails and unique user access. This is particularly important for clinical trial documents, where platforms like Skaldi are designed to support ICH E6(R3) and FDA standards. Industry trends show that 58% of life sciences firms use digital validation systems meeting Part 11 standards, with 35% planning adoption, driven by increased FDA scrutiny. Additional information on how to comply with this FDA regulation on xylemanalytics.com is available.

Throughout this workflow, the system prevents unauthorized modifications, ensures every change is tracked, and secures the final approval with a legally binding electronic signature. The outcome is a defensible and trustworthy record suitable for regulatory submission.

System Validation and Change Control

System validation is a foundational element of 21 CFR Part 11 compliance and a frequent focus of regulatory inspections. Validation is the process of creating documented evidence that a system performs its intended functions accurately, reliably, and consistently. It provides objective proof that a software platform is fit for its intended use in a GxP-regulated environment.

For systems managing clinical trial documents—such as protocols, Investigator’s Brochures, and eTMFs—validation requires demonstrating that the software manages these records as specified. This is a formal, documented process that should be planned and executed before a system is used for regulated activities.

The Validation Lifecycle: A Structured Approach

A structured, risk-based approach to validation is a common best practice. This methodology focuses testing efforts on system functions that could impact product quality, patient safety, or data integrity if they were to fail.

A validation plan typically defines user and functional requirements and outlines a series of qualification protocols.

- Installation Qualification (IQ): This stage verifies that the system is installed correctly according to vendor specifications and internal IT infrastructure requirements. It answers the question, "Is the system installed correctly?"

- Operational Qualification (OQ): This stage tests the system's key functions in a controlled environment. For a document management platform like Skaldi, this would involve confirming that access controls, audit trails, and electronic signature functions operate as designed.

- Performance Qualification (PQ): This final stage confirms that the system functions as expected within the user's real-world operational workflow. It answers the question, "Does the system work for its intended use?" This may involve processing a protocol amendment from initial draft through the complete review and approval cycle.

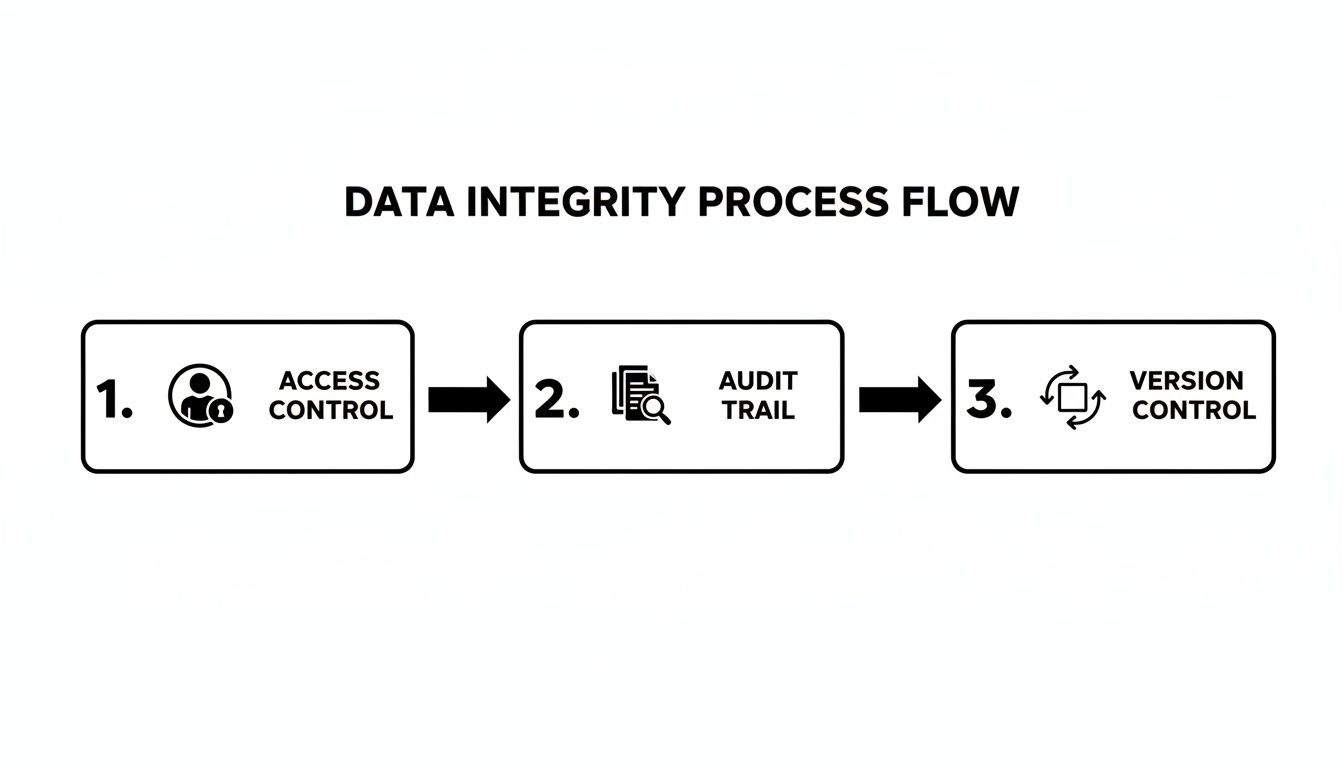

The objective is to create an interconnected flow of controls that ensures data integrity from record creation to archival.

This illustrates how a properly validated system integrates access controls, audit trails, and versioning to provide a secure, traceable environment for GxP records.

Maintaining a Validated State

A common misconception is that validation is a one-time event. Part 11 requires that systems be maintained in a continuous validated state. This means the organization is responsible for managing the system's compliance status throughout its entire lifecycle, from implementation to retirement.

A robust change control procedure is essential for maintaining this state. Any modification to a validated system, from a minor software patch to a major feature update, has the potential to impact its validated status.

A validated system without a documented change control process presents a significant compliance risk. Uncontrolled changes can invalidate previous validation efforts, creating exposure during an audit.

An effective change control process ensures that every modification is formally assessed, documented, tested, and approved before it is implemented in the production environment. This provides a defense against uncontrolled changes that could compromise data integrity or system functionality.

Example of a Change Control Process

Imagine an organization uses a validated platform for authoring Clinical Study Reports (CSRs). The software vendor releases an update that introduces a new collaborative commenting feature.

The organization's change control procedure would be initiated:

- Impact Assessment: A team comprising representatives from QA, IT, and business users assesses the change. They determine the new feature could affect how review comments are captured, which is part of the official record.

- Testing and Re-validation: Because the change affects a GxP function, a targeted re-validation is deemed necessary. This does not necessarily mean repeating the entire initial validation. It may involve executing a specific subset of the original OQ and PQ test scripts to verify the new feature's functionality and confirm it has not negatively impacted existing validated functions, such as the audit trail or e-signatures.

- Documentation and Approval: All test results are documented in a validation summary report. Following QA review and approval, the change is formally authorized for deployment.

This systematic approach maintains the system's ongoing state of compliance as it evolves. By mastering both initial validation and ongoing change control, organizations can build confidence in their electronic systems and remain prepared for regulatory inspections.

Implementing Electronic Signature Workflows

Under FDA 21 CFR Part 11, electronic signatures must be treated with the same legal authority as handwritten signatures. As such, their implementation is a common point of focus during regulatory inspections.

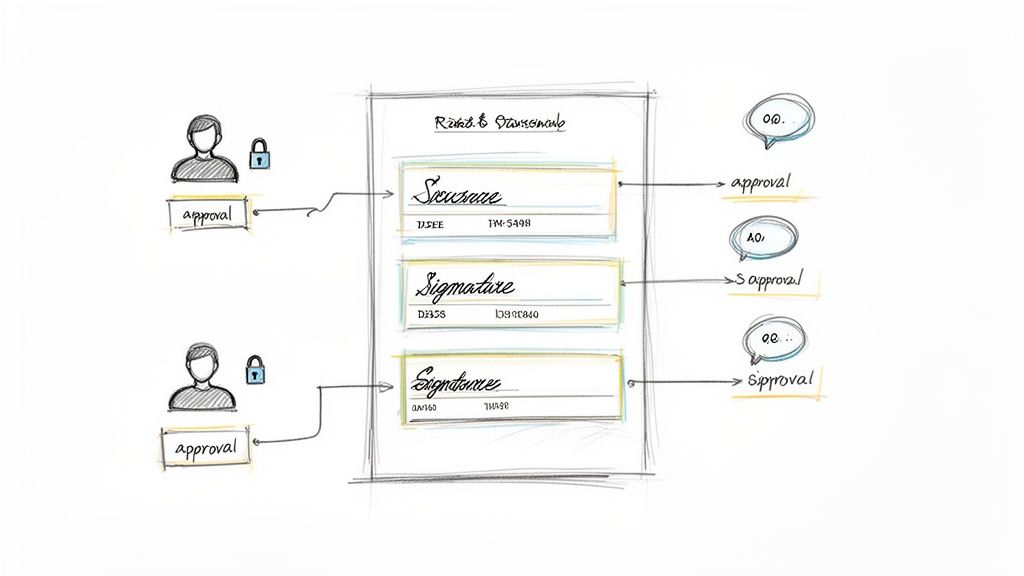

A compliant electronic signature is not merely a typed name; it is a secure data compilation that confirms a specific individual performed a specific action at a specific time.

To be compliant, the system must capture and permanently bind three key pieces of information to the electronic record:

- Identity: The printed name of the signer.

- Time: The date and time the signature was executed.

- Meaning: The purpose of the signature, such as "approval," "review," or "authorship."

These components must be securely linked to the electronic record in a way that prevents them from being excised, copied, or otherwise transferred to falsify an electronic record.

Securing the Signature Act

Part 11 specifies the method by which a signature must be executed. It requires a two-component identification method at the time of signing to confirm the signer's identity and intent.

Typically, this is accomplished by requiring the user to enter their unique user ID and a private password.

This two-factor process confirms the identity of the individual executing the signature. The system must prompt for these credentials each time a signature is applied to a GxP record, reinforcing individual accountability for every approval and sign-off.

A compliant electronic signature is the output of a meticulously controlled process. It ensures every approval is intentional, traceable, and permanently linked to the document's history.

This is a bedrock principle of FDA 21 CFR Part 11 compliance, elevating a user action into a legally binding event and creating a digital record that can withstand regulatory scrutiny.

Example: A CSR Approval Workflow

Consider a common operational scenario: the final approval of a Clinical Study Report (CSR) using a controlled platform like Skaldi.

Before a CSR is submitted to a regulatory authority, it typically requires sign-off from multiple stakeholders, including the lead medical writer and the Chief Medical Officer (CMO).

A compliant workflow would proceed as follows:

-

Initiate the Signature Cycle: Once the CSR is finalized, the document owner initiates a pre-configured approval workflow. The system automatically routes the document to the first approver, such as the Head of Biostatistics, for review and signature.

-

Apply the First Signature: The biostatistician logs into the system. After reviewing the CSR, they select the "sign" action. A dialog box appears, stating the meaning of the signature (e.g., "Statistical Review and Approval") and prompting them to re-enter their user ID and password.

-

Capture in the Audit Trail: Upon confirmation, the system embeds their electronic signature into the document. Concurrently, the audit trail records a new, unalterable entry containing the user’s name, the exact time, and the meaning of their signature.

-

Route to the Next Approver: The workflow then automatically routes the CSR to the next individual in the sequence, such as the CMO. The CMO follows the same two-component authentication process to apply their "Final Approval" signature. Each new signature is added to the document's manifest and recorded in the audit trail.

This structured process ensures the final CSR is supported by a complete, traceable, and compliant approval history. Each signature is securely linked to the specific version of the document it pertains to, creating a defensible record for inspectors.

Today, FDA 21 CFR Part 11 compliance is integral to operational efficiency in life sciences. As more companies adopt digital systems and cloud platforms, the automation of these workflows becomes essential. With validation workloads increasing for 61% of firms, tools with built-in controls for electronic records and signatures are necessary for maintaining an audit-ready state and finalizing submissions. You can discover more insights about this trend in life sciences for 2025.

Developing Procedural Controls and Training

Implementing a validated system is a significant step, but it represents only one part of achieving FDA 21 CFR Part 11 compliance. The other critical components are procedural controls and personnel training. A technically compliant system can fail during an inspection if the organization lacks robust procedures and documented training for its users.

Procedural controls are formalized through Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). SOPs serve as the official instructions for how personnel interact with validated systems and the electronic records they contain. They translate the regulation's requirements into clear, actionable steps for the team.

Establishing Essential Standard Operating Procedures

Well-defined SOPs are the backbone of a compliance program, ensuring that GxP-related actions are performed consistently. An effective SOP is detailed enough to guide a trained user through a process without ambiguity. SOPs must be version-controlled, formally approved, and readily accessible to all relevant personnel.

Key areas requiring dedicated SOPs include:

- System Use: This SOP should define the intended use of the system and map out specific workflows, such as the process for creating, reviewing, approving, and archiving clinical documents like protocols and CSRs.

- Security Management: This SOP outlines procedures for user access management, including granting and revoking access. It should also define password policies, session timeout rules, and the response plan for security incidents.

- Change Control: This procedure must detail the entire lifecycle of a system change, from proposal and risk assessment to testing, approval, and implementation.

- Data Backup and Recovery: This SOP documents the schedule and methods for backing up electronic records and their audit trails. It must also include a plan for data restoration and periodic testing of that plan.

These documents link a system's technical capabilities to consistent, compliant user behavior. A modern regulatory document management system can support these procedural controls with built-in, compliant workflows.

Building an Effective Part 11 Training Program

Technology and procedures are only effective if personnel understand their roles and responsibilities. Part 11 is explicit in requiring that individuals who use electronic record/electronic signature systems have the "education, training, and experience to perform their assigned tasks." This necessitates a documented, role-based training program.

Training should be an ongoing process, not a single event. It should include initial training for new employees, periodic refresher training, and targeted updates whenever a system or SOP is modified.

A common finding during FDA inspections is not the absence of a compliant system, but a failure to adequately train personnel on its compliant use. Documented training records are as important as the system validation summary report.

A practical training program should explain the "why" behind the procedures, not just the "how." The curriculum should cover:

- Principles of Data Integrity: Review the importance of ALCOA+ (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate) and its application to daily work with electronic records.

- Electronic Signature Responsibilities: Emphasize that an electronic signature is the legal equivalent of a handwritten one and must not be shared, delegated, or otherwise compromised.

- Security Protocols: Instruct users on creating strong passwords, the importance of not sharing credentials, and how to identify and report potential security risks.

- System-Specific Workflows: Provide hands-on training that walks users through the specific tasks they will perform in the system, in accordance with official SOPs.

As life sciences firms increasingly adopt digital tools, compliance gaps under FDA 21 CFR Part 11 persist. Issues like inadequate SOPs and inconsistent training are frequently cited in FDA inspection findings. The regulation, established in 1997, requires that electronic systems serve as a trustworthy substitute for paper, a principle highly relevant to clinical operations where every change to a statistical analysis plan or CSR must be captured in a secure audit trail. A recent report indicated that 61% of organizations experienced an increase in validation demands, prompting many to increase budgets to address procedural and technical deficiencies. You can read more about what you need to know for 21 CFR Part 11 compliance in 2025 on dotcompliance.com.

Ensuring Long-Term Record Retention and Retrieval

Finally, procedures must address the complete lifecycle of an electronic record, including long-term retention. FDA regulations require that GxP records be maintained for specified periods, often for many years after a study is completed or a product is no longer marketed.

A formal retention policy, documented in an SOP, must ensure that electronic records and their associated audit trails remain complete, accurate, and readily accessible throughout their required lifespan. This extends beyond data backups to include a strategy for technology migration, ensuring that records created today can be read and interpreted by future systems. This forward-looking planning connects system capabilities with durable, inspection-ready processes.

Frequently Asked Questions About Part 11 Compliance

The operational application of FDA 21 CFR Part 11 often raises practical questions for professionals in the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and CRO sectors. Below are answers to some common inquiries.

Does Part 11 Apply to Draft Documents?

The applicability of Part 11 is determined by the "predicate rule"—the underlying FDA regulation that requires the record to be created and maintained.

A working draft of a document, such as a protocol stored on an individual's local drive, is not typically subject to Part 11 requirements. However, once that draft is uploaded into a controlled system for formal review, approval, or archival, the context changes.

At that point, the document becomes an electronic record within a regulated system, and all Part 11 controls—including audit trails, access restrictions, and version history—apply to its entire lifecycle through to the final, signed version. The distinction is between an informal draft and a record being managed within a formal, GxP-compliant process.

What Is a "Hybrid System" and What Are Its Risks?

A hybrid system combines electronic records with paper-based, handwritten signatures. A common example is generating a final CSR electronically, printing it for a wet-ink signature, and then scanning the signed page back into the electronic system.

Regulators generally view such systems as introducing unnecessary complexity and risk. The organization becomes responsible for proving the authenticity and integrity of both the paper and electronic versions of the record.

The primary challenges associated with hybrid systems include:

- Version Mismatches: There is a risk that the electronic file may differ from the version that was printed and signed.

- Record Integrity: The signed paper copy becomes the source document, making it vulnerable to loss, damage, or degradation over time.

- Weak Linkage: It can be difficult to definitively prove that a specific wet-ink signature corresponds to a specific final electronic version of the record.

Furthermore, with a hybrid system, the signed paper record must be managed in accordance with all applicable GxP regulations for physical documents, adding another layer of operational complexity.

The objective of Part 11 is to enable a single, reliable source of truth. A hybrid system divides that truth between a digital and a physical copy, which complicates audits and introduces compliance risks.

How Often Should a System Be Re-Validated?

System re-validation is not performed on a fixed schedule (e.g., annually). Instead, the goal is to maintain the system in a constant "validated state."

Re-validation activities are event-driven and managed through the organization's change control process.

Any change to the system—such as a software update, a server configuration modification, or a security patch—must be formally assessed for its potential impact on the validated state. If the change could affect a regulated function (e.g., data integrity, security, audit trails), then some level of re-validation is required. This may range from targeted testing of the affected functionality to a more comprehensive re-validation effort, but it must be completed before the change is implemented in the production environment. This proactive management of change is a core principle of maintaining a continuous state of compliance.