Regulatory documents form the official, auditable record of a clinical trial. They function as the detailed architectural plans and operational specifications for the study. Documents such as the protocol, Investigator's Brochure, and Informed Consent Form establish the scientific and ethical framework, guiding every action taken during the study.

The Framework for Clinical Trial Compliance

In clinical research, these documents serve as the operational backbone. They create a structured, verifiable narrative demonstrating that a study has adhered to applicable regulations and the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP). During a regulatory inspection by an agency like the FDA or EMA, this documentation provides the primary evidence that patient safety was maintained and that the resulting data is credible.

Each document serves a specific function, but they collectively provide a comprehensive account of the trial. This structured system is essential for demonstrating to regulators that the clinical development process is under control.

Harmonizing Global Standards

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) provides guidelines to promote consistency in clinical trials globally. ICH guidelines establish a unified standard, which allows data from a trial conducted in one region to be acceptable to regulators in another. This global framework enables sponsors to conduct multinational trials that meet harmonized regulatory expectations.

A thorough understanding of these standards is a foundational requirement for professionals in this field. An overview of the core principles is available in this guide on ICH guidelines for clinical trials.

Rigorous application of these principles helps ensure that documentation withstands regulatory scrutiny, regardless of where the trial is conducted. This consistency is fundamental to building the regulatory trust required for the potential approval of a new therapy.

A meticulously managed document portfolio is not just a regulatory requirement but a critical asset. It is the definitive proof that a clinical trial was conducted responsibly, ethically, and in accordance with established scientific principles.

The table below provides a summary of essential documents and their functions.

Core Regulatory Documents and Their Primary Function

| Document | Primary Regulatory Basis (ICH) | Core Function |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol | ICH E6 (GCP) | The study's "master plan" detailing objectives, design, methodology, and statistical considerations. |

| Investigator's Brochure (IB) | ICH E6 (GCP) | Compiles all clinical and nonclinical data on the investigational product for investigators. |

| Informed Consent Form (ICF) | ICH E6 (GCP) | The document used to inform potential participants about all aspects of the trial before they agree to join. |

| Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) | ICH E9 | Provides a highly detailed, technical explanation of how the final study data will be analyzed. |

| Clinical Study Report (CSR) | ICH E3 | The final, comprehensive report of the trial's results and their interpretation. |

These key documents form the bedrock of any trial's TMF, and a functional understanding of them is crucial for maintaining compliance and inspection-readiness.

The Growing Volume of Documentation

The volume of clinical trial documentation is increasing. In 2024, 10,503 new Phase I–III trials were initiated globally, a 5.5% increase from the previous year, as detailed in the 2025 annual clinical trials roundup.

Each new study requires a complete set of protocols, consent forms, and investigator brochures. This volume amplifies the cycles of drafting, review, and version control. A single clinical program can generate numerous versions of a document, each of which must be traceable and audit-ready, particularly under evolving frameworks like ICH E6(R3).

Understanding Foundational Trial Documents

A clinical trial is built upon a foundation of essential documents. These are not merely administrative paperwork; they are the operational blueprints that define the trial’s scientific purpose, ethical boundaries, and procedures. Correct preparation of these documents from the outset is a prerequisite for ensuring patient safety and study integrity.

The three core foundational documents are the Clinical Trial Protocol, the Investigator's Brochure (IB), and the Informed Consent Form (ICF). Each is a requirement under Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, specifically ICH E6, and they function interdependently to protect participants and produce credible data.

The Clinical Trial Protocol: The Study Blueprint

The protocol serves as the single source of truth for a trial. It is the detailed instruction manual that specifies how the study will be conducted, minimizing ambiguity in execution. Its primary function is to ensure that all procedures are performed consistently across all sites.

This document specifies:

- Objectives and Endpoints: The scientific questions the trial aims to answer and the specific metrics used for evaluation.

- Study Design and Methodology: The participant population, treatment regimens, and study design elements like randomization and blinding.

- Statistical Considerations: The plan for data analysis and the sample size required to achieve statistically meaningful results.

A well-defined protocol is a primary defense against inconsistent data and procedural deviations. For those drafting one, using a structured framework, such as a comprehensive clinical trial protocol template, can help ensure all regulatory and operational elements are addressed.

The Investigator’s Brochure: The Product Profile

While the protocol outlines how to conduct the study, the Investigator’s Brochure (IB) provides comprehensive information about what is being studied. The IB is a compilation of all clinical and nonclinical data available on the investigational product (IP), intended for investigators and their site staff.

The IB provides investigators with the scientific background necessary to understand the IP’s risk/benefit profile, enabling them to make informed decisions regarding patient safety and monitoring. The IB is a dynamic document that must be updated at least annually and whenever significant new safety information becomes available.

The IB is the definitive encyclopedia for the investigational product. It gives investigators the knowledge they need to responsibly manage the IP and handle any potential adverse events, which is central to their ethical and medical duties.

The IB contains summaries of the product's pharmacology, toxicology, pharmacokinetics, and any data from previous human trials, providing a complete scientific history.

The Informed Consent Form: The Participant Agreement

The Informed Consent Form (ICF) is central to ethical clinical research. This document translates the complex scientific information from the protocol and IB into clear, understandable language for a potential participant. Its purpose is to ensure that an individual's decision to participate in a trial is voluntary and well-informed.

An effective ICF must clearly explain:

- The study's purpose, procedures, and duration.

- Potential risks and benefits, along with available alternative treatments.

- The participant's right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

The process of obtaining informed consent is as critical as the document itself and is intended to be a dialogue. Before use, the ICF must be approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committee (EC) to ensure it meets all standards for participant protection.

Together, the protocol, IB, and ICF form a regulatory tripod, with each component supporting the others to maintain a trial that is scientifically sound, operationally clear, and ethically grounded.

Analyzing Data and Reporting Trial Outcomes

After the last patient visit is complete and all data has been collected, the data analysis phase begins. This stage relies on two key documents: the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and the Clinical Study Report (CSR). Together, they transform raw data into a structured narrative for regulatory review.

If the study protocol is the architect's overall vision, the SAP is the engineer's detailed schematic. It specifies the precise methods for data analysis, which is crucial for preventing analysis plans from being altered after the data is observed, a practice that can introduce bias.

The Statistical Analysis Plan: The Technical Blueprint

The SAP provides a detailed description of the "how" of the data analysis, expanding on the principles outlined in ICH E9 guidance on Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials. It is a separate, standalone document that provides specific instructions for biostatisticians.

The SAP must be finalized and signed before the database is locked and treatment assignments are unblinded. This timing is a critical control measure that demonstrates to regulators that the analytical methods were pre-specified and not selected to produce a favorable result.

A comprehensive SAP will specify:

- Detailed Definitions: It defines elements such as the primary endpoint, analysis populations (e.g., Intent-to-Treat vs. Per-Protocol), and methods for handling missing data.

- Statistical Models: It explicitly names the statistical tests for each endpoint. For example, it might specify an ANCOVA model for the primary endpoint and list the exact covariates to be included.

- Mock Shells: The SAP includes empty templates of all tables, listings, and figures (TLFs) that will appear in the final report, showing the exact structure of the outputs before data is populated.

This level of detail makes the analysis defensible, repeatable, and transparent.

The Clinical Study Report: The Definitive Trial Narrative

Following the execution of the SAP, all results, interpretations, and study details are consolidated into the Clinical Study Report (CSR). This is the final, comprehensive account of the trial. Its structure is guided by ICH E3 on the Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports, which facilitates review by regulatory agencies such as the FDA and EMA.

The CSR is a substantial document, often running to hundreds or thousands of pages with appendices. It presents the full narrative of the trial, from the initial scientific rationale to the final conclusions on the investigational product's safety and efficacy.

The CSR is the definitive historical record of your trial. For regulators, it's the single most important piece of evidence they use to decide whether a new therapy is safe and effective enough for approval. The quality of this document can literally make or break a submission.

The development of these documents requires collaboration between biostatisticians, who write the SAP and perform the analysis, and medical writers, who draft the CSR narrative. Clinical scientists provide medical context to ensure the conclusions are both statistically significant and clinically meaningful. This collaboration results in precise documents prepared for regulatory review.

Managing the Trial Master File for Inspection Readiness

The Trial Master File (TMF) is the complete collection of records for a clinical trial. As mandated by ICH E6(R2), the TMF provides the evidence that the trial was conducted in compliance with regulatory requirements, allowing for reconstruction and evaluation of the study.

During an inspection, the TMF is a primary focus. It provides insight into the protection of participant rights and safety and the credibility of the collected data. A poorly maintained or incomplete TMF can lead to significant regulatory findings. In its electronic form, the eTMF, its purpose remains unchanged.

Sponsor TMF vs. Investigator Site File

It is important to distinguish between the TMF maintained by the sponsor and the files located at investigator sites.

- Sponsor TMF: Maintained by the sponsor or its designated CRO, this is the central repository containing essential documents from all participating sites. It provides a comprehensive, top-down view of the trial.

- Investigator Site File (ISF): This is the local file maintained at each clinical site. It contains all documents relevant to that specific site's conduct of the trial, including site-specific logs, correspondence, and signed forms.

The two files contain overlapping content, and ensuring they are synchronized across multiple sites is a significant operational task. For instance, while the sponsor holds the master protocol, each site must maintain its own copy signed by the Principal Investigator. Discrepancies can be a red flag during an audit.

The TMF Reference Model

To manage the thousands of documents a trial can generate, the TMF Reference Model provides a standardized organizational structure. Developed by the Drug Information Association (DIA), it serves as a common index or "table of contents" for any TMF.

By grouping documents into logical zones (e.g., trial management, central documents, site management), the model creates a universal framework. Adopting this model facilitates consistent filing and helps inspectors locate documents efficiently. The complete structure is available in the DIA Trial Master File Reference Model.

Your TMF should tell the complete, unabridged story of your trial. It's a living archive that needs to be updated in real-time—not a historical artifact you scramble to assemble right before an audit. Inspection readiness isn't an event; it's a constant state of being.

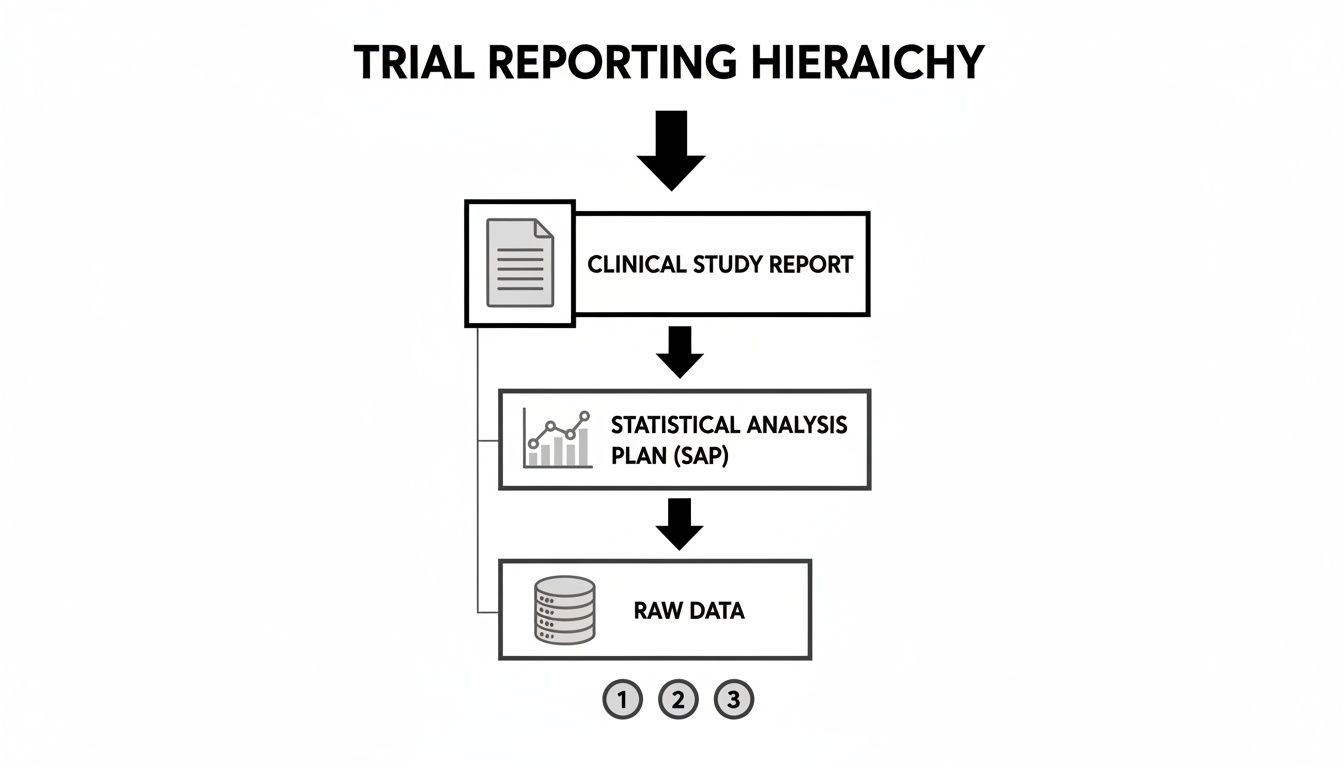

The flowchart below illustrates how core documents contribute to the final Clinical Study Report, a key component of the TMF.

This hierarchy shows that the final report's integrity depends on the quality of the supporting data and documentation, all of which must be filed and accessible in the TMF.

Maintaining a State of Inspection Readiness

A well-maintained TMF relies on disciplined processes, primarily contemporaneous filing (filing documents as they are finalized) and regular quality control (QC) checks. Identifying and correcting issues proactively is preferable to addressing them during an inspection.

Regulatory expectations continue to evolve. The upcoming ICH E6(R3) update and new guidance on areas like real-world evidence (RWE) are influencing how trial documents are authored and managed. The EMA’s 2025 Regulatory Science Research Needs initiative, for example, indicates a move toward more robust and transparent documentation. In this environment, a well-managed, continuously updated TMF is an operational necessity.

Document Control and Quality Management Systems

The protocol, IB, and ICF are critical components of a trial, but the systems for document control and quality management ensure their reliability. A Quality Management System (QMS) provides the operational framework to ensure every document is accurate, traceable, and defensible throughout its lifecycle. It establishes processes to prevent common inspection findings, such as version control errors, missing signatures, or incomplete training records, which can compromise a study's integrity.

The Foundation: Standard Operating Procedures

The foundation of a QMS is a set of clear Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). These are the documented, step-by-step instructions for performing routine tasks. For regulatory documents, dedicated SOPs should cover the entire document lifecycle.

These procedures should be unambiguous and specify:

- Creation and Review: Who is responsible for drafting, and which functions (e.g., clinical, statistics, regulatory) are required for review and on what timeline.

- Approval and Finalization: The process for formal document approval, including electronic signature capture and verification, and how final versions are controlled.

- Distribution and Training: How approved documents are distributed to sites and vendors, and how training on new versions is documented.

- Archiving and Retention: The location and duration for long-term document storage, in compliance with regional retention requirements.

Without documented procedures, processes become inconsistent, which is a common focus for auditors. A well-written SOP reduces ambiguity and promotes a consistent, compliant process for every document.

A QMS is the engine that drives consistency and control. Its purpose is to transform regulatory requirements from abstract principles into concrete, repeatable actions, ensuring that quality is built into the documentation process, not inspected in at the end.

The Proof Is in the Audit Trail

The transition to digital records has introduced specific requirements for managing electronic documents. The integrity of a digital document depends on the system's ability to provide a transparent history of all actions performed on it. The audit trail is a critical component for this.

An audit trail is a secure, computer-generated, time-stamped log that allows for the reconstruction of a document's history. It must capture the "who, what, when, and why" for every action.

A compliant audit trail will show:

- The user ID of the individual who created, modified, or approved a document.

- The exact date and time of the action.

- A description of the action (e.g., "Version 2.0 approved," "Signature applied").

- The reason for a change, if applicable.

Regulatory bodies are increasingly focused on data integrity. The upcoming ICH E6(R3) guidance places greater emphasis on electronic data provenance and audit trails, which have been a source of inspection findings. This trend requires sponsors to incorporate structured metadata and documented QC/QA checks into their controlled document workflows. For more information, you can explore insights on upcoming trial regulatory changes.

A strong QMS, supported by clear SOPs and verifiable audit trails, creates a defensible, closed-loop system that provides evidence of proper document management and demonstrates a culture of quality.

Got Questions About Clinical Trial Documents? We've Got Answers.

The volume of documentation in a clinical trial can lead to operational questions. This section addresses common queries from sponsors, CROs, and clinical operations teams to help maintain compliance and inspection readiness.

How Often Does the Investigator's Brochure Really Need to Be Updated?

The Investigator's Brochure (IB) must be reviewed and updated at least annually and whenever significant new information becomes available, as required by ICH E6(R2) Section 7.1. The purpose is to ensure investigators have the most current safety and efficacy data.

"Significant new information" includes events such as:

- The discovery of a serious and unexpected adverse reaction.

- Results from a new nonclinical toxicology study.

- New clinical trial data that alters the product’s risk-benefit assessment.

Delayed IB updates are a common and avoidable audit finding. Aligning the annual IB review with the Development Safety Update Report (DSUR) preparation cycle is an efficient operational practice, as the data required for both documents overlaps significantly.

What’s the Real Difference Between a Protocol Amendment and an Administrative Change?

Distinguishing between a formal protocol amendment and a minor administrative change is important for operational efficiency. The distinction is based on impact.

A protocol amendment is any change that could potentially affect participant safety, the study's scope, or its scientific integrity. These changes require formal submission to and approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Ethics Committee (EC) and, in some cases, regulatory authorities before implementation.

An administrative change is a minor correction or clarification, such as fixing a typographical error in a non-critical section or updating contact information. These changes do not alter the core scientific or ethical aspects of the trial and are typically documented and communicated without requiring prior IRB/EC approval.

A great rule of thumb is to ask yourself: "Does this change alter risk, patient burden, or the scientific integrity of the study?" If the answer is yes or uncertain, it should be managed as an amendment. If the answer is clearly no, it is likely an administrative clarification.

Can We Start the Next Trial Before the Last Study's CSR Is Final?

Yes, this is a common practice in clinical development. Waiting for a full Clinical Study Report (CSR) to be finalized—a process that can take several months—would significantly delay a development program.

Progression to the next study should be based on available data from the completed trial. This is often managed through a Top-Line Results Summary or an Interim Clinical Study Report.

These documents provide the critical information needed to:

- Inform the design of the next protocol.

- Update the Investigator's Brochure with the latest safety data.

- Support data-driven discussions with regulatory agencies, such as at an End-of-Phase 2 meeting.

This approach allows for program momentum to be maintained based on key data while the full CSR is completed concurrently.

What's the Single Most Common TMF Inspection Finding?

A frequently cited TMF-related inspection finding is a lack of timeliness in filing documents. This means documents were not filed contemporaneously—that is, shortly after they were created, received, or otherwise finalized.

Inspectors may view a TMF that appears to have been assembled just before their visit as an indication of inadequate quality processes. It raises questions about whether the TMF is a true, ongoing record of the trial.

To mitigate this risk, sponsors and CROs should:

- Set clear TMF metrics: Establish targets for the timely filing of documents (e.g., within 15 business days of finalization).

- Do regular QC checks: Conduct periodic reviews of TMF health (e.g., quarterly or monthly) rather than waiting until the end of the study.

- Train everyone: Ensure all study team members understand the importance of timely filing and their specific responsibilities.

An "inspection-ready" TMF is the result of consistent, disciplined processes maintained throughout the trial lifecycle.

How Does the Statistical Analysis Plan Fit in With the Protocol?

The protocol and the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) are related but distinct documents. The SAP is a separate, more detailed document that elaborates on the statistical section of the protocol.

Consider the relationship as follows:

- The Protocol states what will be analyzed. It provides a high-level summary, such as: "The primary endpoint will be analyzed using an ANCOVA model."

- The SAP explains exactly how the analysis will be performed. It provides detailed, step-by-step instructions: "The ANCOVA model for the primary endpoint will include treatment group as the main factor and baseline value as a covariate. The analysis will be performed on the Intent-to-Treat population, and the following method will be used to handle missing data…"

In accordance with ICH E9, the SAP must be finalized and signed before the database is locked and the study is unblinded. This timing is a critical procedural control that ensures the analysis plan is pre-specified before results are known, preventing potential bias in the analytical approach.